Jeff Klein is a 16-year-old high school student from Tyler, Texas, but over the next 20 minutes in Siiri Scott’s summer acting class he’s going to try to become Konstantin, the soul-lost playwright in Anton Chekov’s The Seagull.

Klein’s job this early July morning is to convince Scott and 20 of his peers that his feelings for his errant teenage sweetheart are so powerful that he’s ready to shoot himself if she doesn’t return to him. So he begins: “Nina. I cursed you. I hated you.”

After his first run-through, Scott sees one essential problem with Klein’s performance. “You sound like a smart-ass, Jeff, and you don’t want to. You’re telling us things about yourself that aren’t true.”

Klein gamely accepts Scott’s feedback and sets himself to try again, a dozen or more times, with a little help from his classmates.

First, under Scott’s direction, he’ll attempt to push through four sturdy male classmates in the way a fullback attacks blocking sleds, all the while delivering his lines to the flesh-and-blood Nina who is now standing coolly across the rehearsal room. Soon Scott has him hurling air-like thunderbolts at Nina with every line. When his throws are less than persuasive, she collects candy and pens to put in his hands and force some authenticity.

The method is starting to work. Klein is beginning to get it. A desperate, heartsick, winded youth now commands the rehearsal room of the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center (DPAC). It’s good Klein has made it this far because, as Scott reminds him, he has roughly 24 hours to connect to the rest of Konstantin before auditioning at Chicago’s legendary Goodman Theatre.

Aiming high

Scott doesn’t normally work with high school students; she prepares Notre Dame seniors for careers in theatre. A voice and movement specialist who directs student plays at the DPAC and won an undergraduate teaching award in 2004 from the Kaneb Center, she knows well what it normally takes to get a shot on the Goodman stage: years of professional dedication and a track record of success.

The trip to the Goodman ("No flip-flops, please,” Scott warns her students) exemplifies the kind of opportunities that were available this year to the 250 teenagers who came from all over the United States for Notre Dame’s Summer Experience, one of four summertime recruitment and student development initiatives offered by the Office of Pre-College Programs.

The programs serve several purposes. Notre Dame gets to introduce itself to some of the most talented high school students in the nation and offer them a comprehensive and potentially life-changing taste of undergraduate life. The students receive a high-octane opportunity to hone their thinking about their future, strengthen their college applications and, in the words of the office’s director, Joan Martel Ball ’78, “live the whole Notre Dame experience,” academic, social and spiritual.

“The overriding goal,” Ball says, “is to help the students feel they’re a part of the community . . . that they’re Notre Dame students while they’re here.” This includes “a really rich experience with the Notre Dame faculty. They get to live in the dorms, to do service, to understand why we do service, to have some fun, to make new friends and connect with peers from all over the country.”

Ball credits then-Provost Nathan Hatch with pushing for new academic outreach programs in the late 1990s. Hatch wanted to supplement existing pre-college offerings, such as those run by the colleges of engineering and architecture, and match Notre Dame’s tradition of excellent summer athletic camps. Over time, Ball and her staff created two different styles of programs—the two-week Summer Experience that opens in late June and a trio of tuition-free leadership seminars that follow, one each week, until the end of July.

“We started all of these things with the idea that it really is consistent with the mission of the University,” says Daniel Saracino ’69, ’75M.A., associate provost for enrollment.

The first of the leadership programs, the Global Issues Seminar, was launched in 1998 under the academic direction of Kroc Institute scholar George Lopez. It was designed as a gathering of rising Catholic high school seniors who had survived a highly selective admissions process and demonstrated their readiness to take an undergraduate-level look at international problems.

Ball launched similar programs over the next several years, specifically to reach promising African-American and Latino students. Saracino looks at the three leadership programs as a package, one that is extremely helpful to his office’s mission: “All three of them help our Catholic identity, and all three of them help, I believe, our ethnic diversity.”

Getting to know you

In academic terms, who are those “promising” students being sought? To admissions counselor Christina Brooks, it means kids in the 96th percentile who would be admissible at any highly selective university. That doesn’t mean they are guaranteed admission. But it’s typical for roughly 35 of the 40 students in each of the three leadership seminars to apply and be admitted. Part of Brooks’s job is to interact with the students in the African American Scholars seminar during their week and follow up throughout their senior year to offer support and encouragement.

“We build credible personal relationships with them,” Brooks says. “We know [autumn of senior year] is a tough couple of months, and we want to help them through it as much as possible. A lot of them are surprised by that.”

Once they get over their surprise, the students respond. Some send Brooks pictures and notes about senior year highlights; she’ll call to find out how things went with the big test, the autumn musical or the track meet.

While they receive this personalized attention, once thought to be the kind of treatment reserved for coveted athletes, the students may reflect on their brief but no-nonsense visit to South Bend. Young scholars in the Latino Community Leadership Seminar, for instance, attended lectures on immigration and Catholic social thought. They wrote personal reflections each morning on the nature of leadership, the meaning of being Latino or their personal values. The intellectual work prepared them for a day trip to Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood and The Resurrection Project, an effort to link poor Latinos with affordable housing and financial literacy and educational programs.

The next week, the Global Issues students gathered to study Islam and crises in the Middle East as violence between Israel and Hezbollah militants escalated into all-out warfare. Their visit to a South Bend mosque took place just two weeks after acts of vandalism caused more than $8,000 in damage to a similar Muslim prayer center just 40 miles away.

Saracino would be “very happy” if 50 percent of the students in each seminar group accepted the offer of admission. It’s typical now that not quite 40 percent of these students wind up at Notre Dame, which already represents a solid return on Notre Dame’s investment. While some universities run their pre-college programs as revenue generators, Notre Dame isn’t looking to make money. The program spends little on advertising and connects with interested students primarily through its website and the strong reputations it has with Catholic high schools. Costs for facilities, meals and tuition have been covered year to year by individual benefactors, but Saracino and Ball want to establish permanent funding.

The Summer Experience courses began in 2000. Key differences—such as the $2,200 tuition, a selection of academic tracks, the program’s duration, a higher rate of students who will accept an offer of admission—set them apart from the leadership seminars. Still, the students’ seriousness about their education is on par, and parents don’t seem to doubt they are getting good value for the money. The program has expanded in seven years from four academic tracks and 75 students to 10 tracks serving 250. Next year, 14 tracks are planned. Competition is suitably stiff. Applicants to the new “Voice: Opera and Song” track provide an audition recording (“video preferred”), letters of recommendation, educational and performance resumes, and a repertoire of arias and songs.

These kids haven’t come to Notre Dame to be babied. They’ve come to challenge themselves and figure out what they want to do with their lives—and whether Notre Dame fits in that picture. Virtually all Summer Experience participants say “Notre Dame is my number one choice,” but if pressed further they will acknowledge that the school faces some stiff competition, too.

Cristina Hernandez, 17, one of Siiri Scott’s students in the Acting for Stage and Film track, attends Cristo Rey Jesuit High School in Chicago and will tackle her applications this fall. She has dreamed of becoming an actress since the fourth grade, and she’s interested in Brown, Boston College, Penn State and Berkeley. This is her second Summer Experience—she took the Policy Debate and Public Speaking track in 2005—and she’d like to follow her older brother to Notre Dame. So, if she’s admitted, she says she will gladly accept.

“I would choose Notre Dame. It has a lot of pride in it—you can see it in the students. Everyone is open and friendly, and there’s a lot of opportunity,” Hernandez says.

Jeff Klein, the young Texan who considers acting a “favorite hobby,” hopes to return next summer for the Life Sciences track and, eventually, to pursue a career in medicine. “This is the first place I’ll apply to,” he says, citing the University of Texas or Texas A&M as runner-up choices.

As Ball promises, the opportunities that appeal to students like Hernandez and Klein transcend the hours they spend in the University’s classrooms, labs and studios. Each program kicks off with a late Sunday Mass in the Basilica with the Folk Choir and ends with a liturgy in another memorable part of campus.

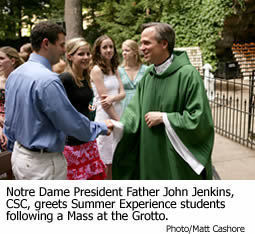

Summer Experience students, about 90 percent of whom are Catholic, convened for a Mass celebrated by University president Father John Jenkins, CSC, at the Grotto on a glorious Friday evening. In his homily, Jenkins urged the students to pray for each other and to “make [it] your ambition to share your gifts with one another.” He reiterated the prophet Micah’s words from the first reading as the essence of the Christian mission: “to do justice, to love kindness and to walk humbly with your God.”

Bonds of friendship form quickly, too. On the quiet eve of the Fourth of July, while friends from home were vacationing with families or partying with friends, a group of Summer Experience students—each from a different academic track—told of a prank war they had fallen into with a group from the separate pre-college program administered by the College of Engineering. It seems the engineers had taken one of the couches from their corner of Morrissey Manor. “So we stole their furniture and fans, pretty much everything they had in their common room,” explained Investments and Entrepreneurship student Martin Colianni, 17, of Naperville, Illinois.

But Colianni and his new pals also had to follow dorm rules even more restrictive than those the University has set for undergraduates. That meant no visiting their female classmates in Lewis Hall, or leaving their dorm after 11 p.m., period.

Ball believes spiritual and social experiences like these help Notre Dame’s pre-college programs stand out from those offered by hundreds of colleges and universities around the country.

Discerning the future

Lest anyone think the programs are simply tasty bait to lure students in the door, it’s worth a visit to Frances Shavers’s Wednesday afternoon yoga class for the African American Scholars seminar. Here the Pre-College Programs’ emphasis on outreach is clearer than is the drive to recruit. Shavers ’90, an executive assistant to the president on normal Wednesday afternoons, today has the students thinking about the importance of breathing. She starts the music on her amplified MP3 player—Al Green’s “Love and Happiness” is first up—and the prostrate students raise their hips from the mats to fill the room with inverted Vs.

Clearly impressed with the students’ focus from his perch at the side of the workout room is Richard Pierce, associate professor of history and chair of the Department of Africana Studies. Now in his second year as the seminar’s academic director, Pierce recalls his decision to shift the week’s focus from leadership to balance, a theme he felt would be apt for young students regardless of ethnicity. The result is almost a retreat: a rare week of personal discernment for these students, all of whom either are Catholic or attend a Catholic high school.

“I wanted the students . . . to think about creating a mission statement for their life, one that would be equally appropriate whether you’re 65 or 20.” Getting through high school and succeeding in college are worthwhile endeavors, Pierce says, “but once you’re in your mid-20s, you’re done with that.” Pondering one’s personal mission and hopes for one’s generation leads to a life one can profitably reflect upon any time, he says.

Saracino confirms the value of this emphasis on discernment. “It’s not just about recruiting. We’re hoping with our leadership programs to introduce the best and the brightest young men and women to Notre Dame. But we also feel that we are giving a great service to high school students who are thinking of college . . . in terms of helping them discern what their academic strengths and interests are.”

Yoga class—like the students’ visit earlier in the day to the Robinson Community Learning Center on South Bend Avenue; like the evening prayer services; like the seminars they’ve taken on literature and the Civil Rights Movement; like the advice they’ve received on college admissions, financial aid and the first year at Notre Dame—is part of Pierce’s curriculum on balance. The entire process is geared toward helping the students “identify a college that meets their goals,” says program counselor Shawtina Ferguson ’05.

“A lot of them weren’t looking at Notre Dame” before the week began, she notes. By the time they leave, she predicts that most of them will be ready to apply.

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine.