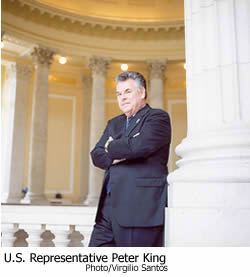

Editor’s Note: Peter King ’68J.D. announced last week that he’s retiring next year at the end of his 14th term in the U.S. House of Representatives. The Republican congressman from New York’s 2nd district on Long Island was the subject of this 2006 profile that chronicled the rise of a “pugnacious polemicist” whose stubborn independence won him friends and foes across the political spectrum.

He is a Republican who nevertheless defied party leaders during their push to impeach President Bill Clinton. He is a practicing Catholic, staunchly pro-life, who has bitterly skirmished with church leaders over illegal immigration. He defends Bush administration tax cuts that primarily benefit the rich, yet shows his loyalty to the lunch-bucket boys by ripping conservatives who resist proposals to boost the minimum wage.

He is a pugnacious polemicist willing to takes on all comers. He calls politics a contact sport. Yet he manages to be known as an amiable and unpretentious guy who holds no grudges and maintains across-the-aisle friendships with Democrats. Scorning the sanctimony that in Washington often tries to pass as principle, he invokes Catholic teaching on original sin to explain why he’s not quick to pass judgment.

He is U.S. Representative Peter King ’68J.D., in his seventh term representing New York’s Long Island. The son of a New York City cop, he is one of the most stubbornly independent and original thinkers in a Republican caucus that House Majority Leader Tom DeLay disciplined with an iron hand until scandal forced him from office.

“If he isn’t unique, he’s near-unique,” says CNNs political pundit Mark Shields ’59, who marvels at King’s ability to rise to the chairmanship of the Homeland Security Committee despite his independent ways. Such coveted committee positions usually go to veterans who keep leadership happy by flying in formation and raising money for the party’s campaign war chests.

Shields says King got the job because of his reputation for smarts, toughness and determination on the national security issues that were thrust to the top of the national agenda by the 2001 terrorist attacks in New York and at the Pentagon. Party leadership decided that the maverick from Long Island, who lost more than 150 constituents and friends on September 11, was just the man they wanted out in front on homeland security, Shields said.

“What makes Peter King tick is that he wants to find the truth about things and he’s not afraid,’’ says Ed Koch, the Democratic former mayor of New York. “I love him for it. There are so few people in political life who are like that. Most of them just think about the next election and feeding at the public trough.”

King, 62, a burly man with a thick mane of black hair, bantered easily in his Capitol Hill office jammed with memorabilia from three passions: Notre Dame, his boyhood home in New York City and politics.

The two visitors’ chairs in front of his desk flank the ND leprechaun on a “Fightin Irish” welcome mat. Football posters, a football autographed by Ty Willingham, and photos of King with Ara Parseghian, Digger Phelps and Muffet McGraw are scattered among posters honoring the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers, the stickball he played on the streets, and the dozens of presidents and world leaders he has met during his 14 years in Congress

One wall holds a newspaper story about King’s lifelong love of boxing, with a picture of him ready to unload a right on trainer and sparring partner Chris Cardona of Long Island’s Bellmore Kickboxing Academy, who describes his student in a way that reporters in the House press gallery find familiar.

“He comes straight in, looking to throw bombs. And he isn’t afraid to get hit.”

King acknowledges his inclination to that bombs-away style in the political arena as well. “You can’t be cautious,” he says. “You can’t be reckless either. But if you believe in something you go in and what happens, happens."

The signature King moment came in 1998, when Tom DeLay was beating the drum for impeachment and demanding that House Republicans fall in line.

King was a conscientious objector against the furiously partisan war. His multilayered, carefully articulated reasoning reflected Catholic theology, his owned nuanced distinction between sins of weakness and sins of malice, and his lawyer’s sense of the importance of precedent.

“My Catholic upbringing and the idea of original sin taught me not to be too quick to judge other people, especially on sins of weakness,” says King. “If a person intentionally hurts someone, I find that pretty unforgivable. But with sins of weakness, don’t be too quick to judge.” So while Clinton’s lying about his Oval Office dalliances with Monica Lewinsky stoked DeLay’s fury, King was convinced that impeachment would be both morally wrong and constitutionally dangerous.

“I thought it was too easy to gang up on President Clinton,” he says. “But more than that, I thought it was a terrible precedent to, in effect undo an election.”

As King faced off against DeLay, he initially had plenty of support from a cadre of Republican moderates. But they slowly peeled off as DeLay cracked the whip, threatening to support challengers in primary races against the rebels. DeLay aide Michael Scanlon, now disgraced and convicted in the Jack Abramoff lobbying scandal, warned that unless King relented, the next two years would be “the toughest of your life.”

As the showdown unfolded, King felt like Gary Cooper in his favorite movie, High Noon, the Cold War era classic about a brave man stepping alone into the middle of the street to confront evil as his former allies cowered in the shadows. Like the Cooper character, King took on the fight as fellow Republicans looked on.

“Some of them had been 1,000 percent against impeachment, but then they wouldn’t take my call,” King says. “So I knew what was happening.”

A blue-collar background

King traces that stand, like much of what animates him, to the lessons he learned in the blue-collar neighborhood of his youth. Many of them came from his father, the son of Irish immigrants, whose picture has a permanent spot behind his desk.

“He always said, ’If you’re going to do something, don’t count on everyone being with you. Do it because you can stick it out yourself.’”

Those lessons explain his respect for the blue-collar families he regards as the bedrock of the American society, even if many Republicans turn the other way with their anti-union, low-wage politics.

“I like to give a break to the working guy,” says King, a friend of AFL-CIO President John Sweeney. He rails against Republicans who fight proposals to hike the minimum wage and attack labor unions as corrupt.

“Instead of going for solid working people, people who work hard, are patriotic and put their kids through school, the people who would be role models for Republican campaign commercials, we’re driving them away,” he said in 1996.

In recent months King has been skirmishing bitterly with Catholic bishops over immigration policy. Alarmed at illegal immigration, he is angry at the bishops’ denunciation of a tough bill passed by the House of Representatives at the end of 2005.

King’s suggestion that the bishops “should spend more time protecting little boys from pedophile priests,” outraged Bishop Thomas Wenski of Orlando. “To content himself at taking cheap shots at the bishops shows that he is unable to engage us on the issues — because his position defies logic and certainly does not represent the ‘compassionate conservatism’ of his party’s leader,” says Wenski

King’s long-standing willingness to criticize church leaders also has roots in his childhood, where he was both a victim and witness of cruel physical punishment by the nuns at Saint Teresa’s elementary school.

He recalled for Newsday, the Long Island daily, the story of a nun’s frustration with a girl who struggled with an arithmetic problem.

“I saw the nun standing behind her grab her by the hair and smash her face into the blackboard. Her nose was bleeding, and the nun started talking about the family’s tragedy, belittling her, telling the kid, ‘Is that the best you can do? Is that the best you can do?’’

Half a century later, King is still driven to restore order in an often chaotic and unjust world. He even tries to work things out in fiction.

The author of three novels, King shares his identity as a congressman and Notre Dame Law school grad with Sean Cross, the tough-talking central figure of his last two forays into fiction.

The books braid historical narrative into fictional ruminations about two crises in which King has immersed himself: the troubles in Northern Ireland and the new age of terror launched by the attacks of September 11. In Deliver Us From Evil, King’s novel on the peace process in Northern Ireland, he details his friendship with the IRA’s Gerry Adams and his close work with Clinton on the Peace Accord.

“Writing helps you make sense out of what you’re doing,” says King. He wryly acknowledges that he enjoys an author’s omnipotence and freedom from the Tom DeLays of the world.

“You can kill people. You can resurrect people. You can save people,” King says. “I like that.”

Jerry Kammer is a correspondent in the Washington office of Copley News Service. Immigration and U.S.-Mexico relations are his beat, though he spent most of 2005 investigating the bribery scandal involving disgraced former California Representative Randy “Duke” Cunningham.