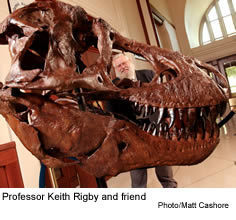

A new face with a toothy grin now greets patrons of Notre Dame’s Eck Visitor’s Center. A replica of the skull of “Peck’s Rex,” the Tyranosaurus rex fossil discovered in 1997 by a crew led by Notre Dame paleontologist J. Keith Rigby, Jr., went on display at the University in May. The 66-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus fossil, which derives its name from its discovery site near Fort Peck, Montana, made the national news when a ranch family claimed ownership and attempted to dig it up before Rigby’s crew could excavate it. Subsequently, legal authorities established that the family did not have title to the land and forced them to return the skull and other bones to Rigby. Recently, we had a brief chat with Notre Dame’s dinosaur hunter.

NDM: Just how significant is Peck’s Rex?

Rigby: There are approximately 25 known specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex in the world. Of that number, five or six are reasonably complete skeletons, 80 percent or more whole. This specimen would be in that elite group. We have found some pieces that are rarely found. We probably have the world’s only complete hand for a T. rex, including the very small third finger which is about the same size as your small finger. We also have the breastbone, akin to the wishbone in a turkey, which is the critical feature linking the dinosaur to birds.

NDM: Were you surprised by anything when you began analyzing the fossil?

Rigby: T. rex is supposed to be the top dog of the dinosaur world, “Mr. and Mrs. Tough,” that’s the popular image. But it might not have been the case. One of the intriguing things we’ve found is that Peck’s Rex has bite marks all over its skull. It fought. We see evidence of wounds and cysts. There are signs of arthritis in the jaw bones. It may even have had a serious case of bone cancer. The overall impression is of a creature not in good health. This is causing us to look at all the other dinosaur specimens more closely. In fact, “Sue,” the famous T. rex in Chicago’s Field Museum, has broken bones and bite marks. T. rex did not have a white-collar lifestyle. It lived in a tough neighborhood and survived by tooth and claw.

NDM: Finding Peck’s Rex must be a high point in your career.

Rigby: There’s a piece of me that hopes we never find another one. This has been very difficult. We’ve been assembling and preparing it for display for over five years and we’ve just now gotten to the point that we can begin to study it and publish our findings. The problem is you can’t analyze something sitting in a block of rock. This particular fossil was so difficult because the sediments surrounding the bones hardened shortly after the skeleton’s burial. Consequently, the bones never had any mineral content added to them. That means the surrounding rock is much harder than the bones, so recovering the fossil was like taking concrete off of marshmallows. We use these miniature jack hammers, about the size of a pencil, trying to knock off the rock and do minimal damage to the bone. After the bones are cleaned, molds are made and from these we make casts of the bones. It’s the casts that are assembled and put on display. The fossils themselves, which have an estimated value of $16 million, are kept in a vault at the Fort Peck Interpretive Center in Montana and are available only to researchers.

NDM: Are you on the trail of any other dinosaurs?

Rigby: This summer, from the same hill where we discovered Peck’s Rex, we recovered a triceratops, the plant-eating dinosaur that looks a little like a rhinoceros. We also excavated a hadrosaur, a duck-billed plant eater, and another human-sized dinosaur. Those were our three primary targets this year. We have leads on half a dozen other things as well. Besides dinosaurs we even have a fossilized stump of a bald cypress tree that is 17½ feet in diameter at the base and 8 feet tall.

(October 2003)