Editor’s Note: Notre Dame football’s independent status has been a subject of internal discussion and external debate for decades. Ten years ago, to commemorate the program’s 125th anniversary, we explored the historic roots of Fighting Irish independence — and whether it could be sustained in a changing college football landscape. As a new season kicks off amid more tumult in the sport, the factors addressed in this Magazine Classic by Malcolm Moran, a longtime sports reporter who now directs the Sports Capital Journalism Program at IUPUI, have renewed relevance.

On a clear, crisp Friday afternoon in early February of 1999, 39 members of the Notre Dame Board of Trustees silently departed from a building off Trafalgar Square in London, having declared their independence.

Several hours earlier, at the end of a 90-minute discussion preceded by weeks of intense speculation and debate throughout the Notre Dame community and beyond, a voice vote determined whether the University would pursue membership in the Big Ten conference and its unique academic consortium, the Committee on Institutional Cooperation. The issue had been compared to a pair of decisions that had altered the University’s identity: The establishment of a lay Board of Trustees in 1967, and the admission of women in 1972.

- Related articles

- A Land of Myth and Legend

- More than a Game

This time, however, an identity traced to the 19th century was preserved. “Notre Dame always will be Catholic and always will be private,” Rev. Edward A. Malloy, CSC, the University president, said at a press conference. “Even in terms of size, we will not become appreciably larger. Given these realities, we have had to ask ourselves the fundamental question: Does this core identity of Notre Dame as Catholic, private and independent seem a match for an association of universities — even a splendid association of great universities — that are uniformly secular, predominantly state institutions and with a long heritage of conference affiliation?

“Our answer to that question, in the final analysis, is no.”

The emotional link between the nature of a football program and the University had been settled, it seemed, for another generation. Most of the athletic teams had established their home in the Big East conference, but the national identity of football, which had given the University its unique place during the Rockne era, remained intact.

The preservation of that status had been built upon a premise recently articulated by Gene Corrigan, the former Atlantic Coast Conference commissioner who, as Notre Dame athletic director in 1985, became The Man Who Hired Lou Holtz.

“There are not many people that don’t want to play Notre Dame,” Corrigan said.

More than a decade after Notre Dame’s football status was defined that day in London, the questions linger: Can that premise remain part of a successful strategy? Is football independence a quaint, outdated tradition or a sustainable approach in the 21st century?

“They’re like the only self-inflicted independent in football,” Corrigan said. “Everybody else is either in a conference or wanting to be in one.”

As the institution of Notre Dame football marks its 125th anniversary this autumn, the direction of its future can appear as challenging and complex as the place it occupies in the national landscape. Some of the most successful programs in the nation, including Ohio State and Southern California, have been found to have committed violations so damaging to the credibility of college sports that NCAA President Mark Emmert convened a summit meeting of university presidents during the summer of 2011. That discussion took place nearly three months before the child-abuse scandal at Penn State and the allegations against former defensive coordinator Jerry Sandusky that led to the departure of Hall of Fame coach Joe Paterno and university president Graham Spanier, became a dominant national topic of conversation.

A series of shifts in conference affiliation, elevating revenues to once-unimaginable levels for some leagues and placing the future of others in jeopardy, has led critics to maintain that universities have become more interested in leveraging unpaid athletes to gain access to additional millions in television revenue than they are in providing a meaningful education and the chance to earn a degree. The Big East, which had faced the possibility of a breakup as long ago as the winter of 1994, before Notre Dame’s arrival, is dealing with the latest round of defections and the search for a commissioner at a critical time.

The changes have become as complicated as the negotiated future of the Bowl Championship Series and as clear as the more modest anticipation of an excited, incoming freshman.

In the late 1990s, when football independence was preserved, first-year Domers would approach the ticket windows on the east side of the stadium, off Juniper Road, and pick up their tickets in late summer with the expectation that at some point in their four-year experience they would look to the roof of Grace Hall and see the 8-foot-high No. 1 sign lit up to signify a national championship.

When the Class of 2016 arrives near the end of this summer, the inconsistencies of recent seasons and the shifting priorities of the national post-season structure have combined to revise that hope.

In 1993, the year the Fighting Irish defeated Florida State in an epic No. 1 vs. No. 2 game — remember the bed sheet that read NOBODY LEAVES #1? — the Bowl Coalition determined that Notre Dame would be included in a seven-victory season, or a six-victory season if mutually agreed upon by the bowls and the University. That is how the 1994 Irish, with a regular-season record of 6-4-1, received a bid to the Fiesta Bowl. As 1988 national champions and consistent title contenders, Notre Dame was considered such an essential part of the landscape that the post-season structure all but guaranteed its inclusion. A one-sided loss to Colorado in that bowl game led to a change in the system.

As contending status became a more distant memory, something happened. Decision-makers appeared to determine that a thriving post-season was no longer dependent upon the presence of Notre Dame, whose decision to end its absence of 4½ decades had immediately made the bowl structure more relevant in the early 1970s. The minimum standard for Notre Dame’s inclusion in the best publicized and most lucrative post-season games gradually rose. Now, an automatic berth in the Bowl Championship Series is guaranteed if the Irish are in the top eight positions of the final BCS standings. That’s a long way from a Fiesta Bowl slot for a team not much above .500.

That difference helps explain the renewed questions about potential conference affiliation as the Big East struggles for survival and leaders of colleges and universities attempt to anticipate the next seismic shift in the landscape. Reports have confirmed that since that Friday afternoon declaration in 1999, Notre Dame representatives have conducted conversations — directly or indirectly — with multiple leagues, including the Big Ten and Big 12. That uncertain landscape, and the place Notre Dame occupies in it, can be traced to discussions which took place as the Rockne era had reached an elite level.

In his book, Shake Down The Thunder, Murray Sperber described the outcome of the 1926 discussions with the Big Ten:

In the end, the Big Ten’s failure to admit Notre Dame was based on misperception, not reality. The conference adamantly refused N.D.’s request “to appoint a committee to visit” the Catholic school and “conduct an investigation of all conditions, both academic and athletic.” Instead, the faculty reps chose to believe the rumors about Notre Dame, especially those spread by [Michigan coach Fielding] Yost and [University of Chicago coach Amos Alonzo] Stagg. For “Academic Men,” representing universities that considered themselves on the cutting edge of the scholarly research of the day, their acceptance of anti-Notre Dame gossip was reprehensible.”

Sperber’s analysis of the breakdown described two missed opportunities for reform. With Big Ten schools making a greater investment in football and presenting coaches with higher levels of influence, Sperber reasoned that conference members would have benefited from Notre Dame’s effort to see that a power coach such as Rockne was working within the interests of the university. And Notre Dame, Sperber wrote, would have been aligned with a conference membership publicly committed to reform efforts during a period when there was greater concern over the excesses of college sports.

Nearly 75 years later, as that 1999 discussion triggered emotional responses, decision-makers received thoughtful letters with variations on the same theme: They turned us down in 1926. How dare you talk to them again?

As that response became validated by the vote of the trustees, something else was happening to the nature of the football program and its place in the national landscape. Notre Dame’s success, all the way back to the Knute Rockne era and the mythology created by the New York press, had been built upon national championships that could be secured without having to play in a bowl game. Eight of the 11 championships — as recent as the 1966 title under Ara Parseghian that was secured with the emotionally charged 10-10 tie with Michigan State — were won before the Associated Press permanently established a poll that followed the bowls.

Post-season football was considered more of a curtain call, a chance to see the team once more in a warm, comfortable place, and Notre Dame’s absence from that process from the mid-1920s through the end of the 1960s did not hurt its chances. Even at the end of the 1977 season, on one of the most gripping bowl days in the history of the sport, the Irish could wake up on Jan. 2 with a No. 5 ranking, defeat No. 1 Texas in the Cotton Bowl, and anticipate a national championship vote by the time they went to bed.

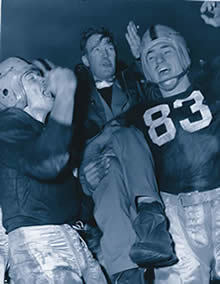

That was the backdrop that created the 20th century measurement which would separate Notre Dame coaches for the ages from others who were perceived to have failed. The third-year national championship had come to define a successful tenure under coaches Frank Leahy, Parseghian and Dan Devine, right up to the 1988 season, Holtz’s third, and the Fiesta Bowl victory over West Virginia that sent him up on to the shoulders of his players and into the status of Notre Dame legend. Freshmen could arrive on campus each summer with the realistic expectation — or even the demand — that a similar celebration would happen in their time.

But as conference commissioners became convinced that the credibility of the bowl system was being threatened by the popularity of expanded professional playoffs, the deal-making, free-market nature of the post-season was replaced by a more antiseptic and structured process. A matchup of the two top-ranked teams, considered a rarity for decades, suddenly became an annual goal.

At the end of the 1992 season, the first year of the Bowl Coalition, the fifth-ranked Irish played in the Cotton Bowl and defeated No. 4 Texas A&M, 28-3. A decade and a half after a convincing victory in Dallas became a launching pad to an argument over the title, this victory was an afterthought to a national audience focused on No. 2 Alabama and its upset of No. 1 Miami in New Orleans. The days of leapfrogging to the top had ended.

Politically, Notre Dame had isolated itself by entering the landmark television deal with NBC in 1991. The University had created a significant source of income for an endowment for undergraduate, nonathletic scholarships, and its national reach had been extended by guaranteeing that home games would not be subject to regionalized coverage. But the political polarization that had characterized the national response to Notre Dame through the ages had intensified in athletic circles.

For most of the Holtz era, none of that seemed to matter. “He was just the right guy for that job,” Corrigan remembered. During the spring prior to the 1986 season, the new coach of the Irish stood before an audience of 200 alumni in the Waldorf-Astoria in New York and described the hiring process. Holtz itemized the non-negotiable realities of the place: the core curriculum, the necessary standardized test scores. Then Holtz remembered the point in the conversation when Corrigan had gotten down to the really hard part.

“He said, ‘You play Michigan, Michigan State, Purdue, Alabama, Pittsburgh, Air Force, Navy, SMU, Penn State, LSU and USC.’”

The room was silent as Holtz paused just long enough.

“He said, ‘Would you like the job?’”

Already, the coach knew his audience.

“You aren’t interested in how rocky the sea is,” Holtz said. “You are interested in seeing the ship come in.”

The frustration of the Gerry Faust era, for all the conversation it inspired in the early 1980s, only lasted five seasons. From a distance, a perception had grown that the performance of the program had evolved into its own cycle. Extended success would lead to a period of self-consciousness, which would lead to adjustments that created disappointment, which would lead to greater resolve and a return to success.

For decades now, the reality has been far more complex.

In his autobiography, God, Country, Notre Dame, Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, addressed the speculation that developed during his presidency in the 1950s.

It was during [Coach Frank] Leahy’s time, or just afterward, that there were some stories going around that I was de-emphasizing football at Notre Dame. Not true. I never deliberately did anything to cut back on football. My belief is, and always has been, that the university ought to do everything — academics, athletics, you name it — in a first-rate manner. That means doing everything not only well, but honestly, too. . . .

With our checks and balances, we set up an honest system in our athletics a long time ago and we have kept it that way. We expect no less from our coaches. In my day, before officially signing on a football or basketball coach, I would sit down with him privately and ask if he had read our rules and was prepared to keep to them carefully. The response almost always was that our system for integrity was what attracted him to Notre Dame in the first place.

Despite all the changes taking place nationally, the Holtz era did not feel threatened by change until the end. The balance of a demanding academic structure and elite-level competition appeared to be met. The opportunity for a teenager named Chris Zorich, whose arrival could only take place after he attended a vocational high school in Chicago from 7 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. in his final high school semester, demonstrated the value of the system as he overcame academic self-doubt and became a leader on the field.

During the summer that followed the most recent national championship season, Zorich ’91, ’02J.D. admitted to developing an ulcer during his freshman year, and he told a story on himself. He remembered having a conversation with a female student soon after his arrival on campus, when students awkwardly search for common interests and experiences. They were talking about college board scores when the woman mentioned that her score had been 800. Zorich, whose overall score had been 740, was buoyed by the discovery, until the student became more specific.

“She said, ‘That was in math,’” Zorich remembered. “I thought, ‘Whoa.’”

The Holtz era inspired a stunning rise in hotel rates, the required two-night minimum, and mandatory attendance at the Quarterback Club lunches and pep rallies. It all seemed to work until the very end, when the University’s concern about preserving its high graduation rates introduced another discussion about the price of success. Holtz’s cryptic remarks in a press conference before his final home game in 1996, when he repeated the words “the right thing” without additional explanation for his departure, created more questions than they answered.

The coaches to follow have come from a variety of prototypes. Bob Davie was a highly regarded assistant who would likely have gotten away had he not been hired to succeed Holtz. Tyrone Willingham had taken Stanford to the Rose Bowl, and his presence as the first African-American head coach at Notre Dame placed the University in a leadership role in an industry defined by an absence of opportunities for qualified minority candidates.

When Willingham was fired at the end of the 2004 season, a new and more damaging perception was created. Dave Anderson, the Pulitzer-Prize-winning sports columnist from The New York Times, wrote: “In dismissing Tyrone Willingham after three quick seasons as football coach, Notre Dame, without realizing it, turned pro.

“And maybe it’s finally time for every college with a big-time football program — or big-time basketball program for that matter — to turn pro.

“Stop pretending that big-time college sports are all about ‘the kids’ and academics and graduation rates. It is really all about what should be known as campus pro sports — the big money from television, the football bowl games, the basketball tournament that evolves into the Final Four, the big money from alumni contributions when a college has a hot team.”

The following summer, with the campus community anticipating a new era under Charlie Weis ’78, with his memories from days in the student section and his Super Bowl championship credentials, a reporter paid a visit to a faculty member to tweak him about Charliemania.

“Charlie Weis cannot fail,” the faculty member said.

“What do you mean?” the reporter asked.

“If we keep firing head football coaches every four or five years, a decade from now we could be closer to Vanderbilt than where we think we belong.”

The thread of the Davie-Willingham-Weis years became a continuation of academic success plus athletic achievement that, in the end, did not meet the standard established in another world nearly a century ago. As the University made an unprecedented investment in its football program — with the $50 million expansion of Notre Dame Stadium, the creation of the Guglielmino Athletics Complex, and the dramatic increases in coaching salaries and the size of the athletic administrative staff — the old standard has appeared more and more difficult to meet.

As Brian Kelly starts his third season, the one that established the perception of greatness or failure as recently as a decade ago, that dated measure has received significantly less attention in media reports and analysis. As the status of the Bowl Championship Series was redefined this summer, Corrigan said he believes Notre Dame will be able to preserve its independent status in football and maintain its access to the biggest post-season games.

“Can they keep it there?” he said of football independence. “Yes, they can. But it’s going to be more difficult.”

The mindset of this year’s freshmen, without anything close to a championship season in their lifetimes, is harder to figure out.

Before Lou Holtz’s first season, as he stood in that ballroom in New York, he was asked to define a successful season at Notre Dame. More than a quarter century later, Holtz’s answer still applies.

“Having the opportunity to coach here again,” he said.

Malcolm Moran, the Knight Chair in Sports Journalism and Society, is director of the John Curley Center for Sports Journalism at Penn State University.

Photos from University of Notre Dame Archives.