‘The perfect hall for public entertainments’

Washington Hall has been a busy place since its dedication in 1882, and nearly everyone who has studied at Notre Dame has some memory of it. Some recall attending orientation meetings there when they first arrived or convocations when they were about to graduate. Those getting married may have taken Father Theodore Hesburgh’s renowned Pre-Cana class there. Notre Dame students have filled the auditorium in Washington Hall to see their peers act in plays, to watch movies, to experience music in all its forms, to attend lectures or take classes and examinations. Some have heard the world’s movers and shakers — from Tom Dooley to Mario Cuomo — speak from the Washington Hall stage.

Almost everyone who remembers anything about Washington Hall also has a ghost story to tell about incorporeal bugle players, the famed football player George Gipp, who died of pneumonia in 1920, or accident-prone steeplejacks.

If the Basilica of the Sacred Heart has been the venue for sacred assembly, then Washington Hall has served the vital complementary role for secular assembly in the heart of the historic campus.

When I first visited Notre Dame in early 1984, I walked into a Washington Hall auditorium that looked essentially the same as it had since 1956, despite ongoing renovation. The painted interior, tastefully executed with minimal decoration, had been central to the mid-1950s modernization plans of Father Arthur S. Harvey, CSC, ’47, who directed the University Theatre from 1954 to 1969. Today, few Domers can remember any interior but this modern one.

Similarly, not many Domers also know that Father Harvey’s renovation involved painting over an elaborate interior executed in 1894 by Luigi Gregori and Louis Rusca, the same artists whose efforts on the Basilica and Main Building have now been painstakingly restored. Their interior contained complex, emblematic frescoes and paintings that covered Washington Hall’s every surface.

From 1894 until 1956, audiences seated in the Washington Hall auditorium saw a proscenium arch that included the surnames of the two patriarchs of Notre Dame’s music programs, Professor Maximilian Girac and Father Edward Lilly, CSC, along with trompe l’oeil “statues” of the great classical orators Demosthenes and Cicero. Intertwining images of musical notes, scores and books with the names of contemporary European composers — Rossini, Haydn, Balfe and Gounod — climbed up the arch to the top, where over the stage a stern George Washington, father of the country and namesake of the building, held the Declaration of Independence. Banners proclaiming Pro Deo et Patria and E Pluribus Unum surrounded him.

Beyond the proscenium arch and occupying niches along the curved upper walls sat the emblematic personifications of Tragedy, Comedy, Poetry and Music, accompanied on the ceiling proper by portraits of Shakespeare, Molière, Beethoven and Mozart. Faux marble columns with gold Corinthian capitals surrounded the seating area and appeared to support the entire building, with every surface between them flamboyantly decorated.

It is little wonder Scholastic magazine described the newly completed interior in June 1894 as “this gem, this perfect hall for public entertainments.”

Audiences during the period heard fiery speeches by Williams Jennings Bryan and lectures by G.K. Chesterton and saw films from The Birth of a Nation to Knute Rockne, All American, projected from the back of the balcony onto a screen set up on the stage. They attended full-fledged minstrel shows and later iterations like the “Monogram Absurdities” and witnessed a long tradition of men, including famed football coach Knute Rockne, playing women’s roles before women played those roles exclusively.

They also experienced some of the greatest performers in the nation, from the premier acting troupe of the day, Augustin Daly’s Company of Comedians, to the avant-garde Merce Cunningham Dance Company (with composer John Cage) at the peak of their talents. They saw puppet shows, scientific exhibitions and travelogues. They did all of this under the watchful eye of the Father of Our Country and his supportive cast of painted characters.

Inspired by the work of Sophia Meyers ’10M.A. and Professor Robert Coleman on the former Vatican artist, Luigi Gregori, my archival research on Washington Hall reveals that by 1894 the University had commissioned Gregori, a Notre Dame professor of art from 1874 to 1891, to provide 11 pictures as focal points surrounded and supported by a detailed interior executed by Midwestern fresco artist Louis Rusca. While the original plan apparently called for those iconic portraits of Shakespeare, Molière, Dante and Mozart to be complemented with appropriate muse-like personifications, in the end Gregori seems to have painted Beethoven rather than Dante. We may never know why he made a change that would have compromised this clear and obvious partnering, but it nevertheless seems highly likely that it was Beethoven he wished to be placed adjacent to Poetry.

Gregori returned to Florence in June 1893 after his last visit to the United States. There, in declining health, he executed all 11 pictures on canvas. He had them shipped to Notre Dame, and Rusca installed them directly onto the proscenium arch, walls and ceiling of Washington Hall. Rusca prepared the rest of the auditorium interior, too, including the painted elaborate trompe l’oeil “frames” that would surround each of Gregori’s pieces.

When the pictures shipped, Gregori’s daughter Francesca sent James Edwards, a professor of history who helped shape the University archives, an instructional letter reminding him to be sure Rusca both had properly primed the surfaces where the paintings would be attached and had plenty of workmen on hand to lift the large canvases into place carefully without creasing or folding them (which would cause the paint to flake off during the process). Rusca’s installation of the 11 canvases was probably similar to how we might install wallpaper murals today.

Rusca, a Swiss-Italian who immigrated as a young man to the United States in 1866, deserves a great deal of credit for his timely labor. He got the venue fully prepared by May 1894, so Gregori’s paintings could be efficiently installed the instant they arrived. Since the interior seems to have been completed in time for commencement that June, Rusca had barely two weeks to finish his work.

The 1956 modernization may have destroyed all 11 of Gregori’s paintings. The canvases would almost certainly have been damaged by the scraping and sanding procedures the workmen likely used to prepare the walls and ceiling. Two tones of gray paint helped to transform the space from a late 19th-century multipurpose exhibition hall into a 20th-century purpose-built theatre where Father Harvey would showcase the work of the University Theatre over the next decade and a half.

With the 2004 opening of the spectacular five-venue DeBartolo Performing Arts Center on the south edge of campus, Washington Hall lost its status as Notre Dame’s premier showcase for the performing arts. What then will be the role over the next century for the innovative structure Willoughby Edbrooke designed soon after the Great Fire of 1879 as a key part of the architectural and ideological unity of the central campus?

As I have dug deeper into Notre Dame’s history, I have come to the conclusion that the time has come to restore and, if necessary, reconstruct the Gregori/Rusca grandeur of the past, just as the University has done with both the Basilica and the Main Building. While the ghost of Washington Hall lives in legend, in a very real sense the truer ghost is the work of Gregori and Rusca, some of which inevitably remains, awaiting a restoration that would allow this venerable building to regain its artistic integrity and assume once again its rightful place among the architectural triumvirate of the central historic campus.

Other institutions such as the University of Virginia with its Old Cabell Hall auditorium (1898) — replete with a glorious reproduction of Raphael’s The School of Athens — have done just that as part of larger restoration efforts. Notre Dame should do the same. The 1894 interior, once restored, would both complete the artistic vision we see today in the Basilica and the Main Building while reaffirming the larger vision for the campus’ most historical buildings. Perhaps it is indeed time to make Notre Dame’s first performing arts center once again the gem it was intended to be.

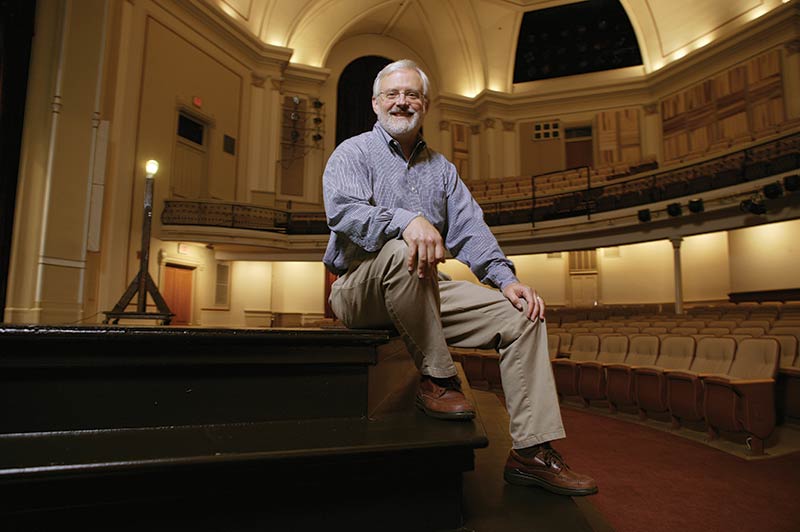

Mark C. Pilkinton is a professor of film, television, and theatre at Notre Dame who directed 10 plays on the Washington Hall stage between 1984 and 2004; 13 of those years he served as chair of the Department of Communication and Theatre. He is the author of Washington Hall at Notre Dame: Crossroads of the University, 1864-2004 . He co-edits the Theatre Chronology database accessible at archives.nd.edu/search/theatre.htm.