Robert Burns immersed himself in ND history, including the firing of Frank McMahon, to write "Being Catholic, Being American."

Robert Burns immersed himself in ND history, including the firing of Frank McMahon, to write "Being Catholic, Being American."

Editor’s Note: Academic freedom is a contentious issue today, but the debate over free inquiry and discourse in higher education — Notre Dame included — is nothing new. This Magazine Classic from 2013 looks back at the story of a philosophy professor “unceremoniously cashiered” from the University over political statements in 1943, the ensuing firestorm, how Notre Dame’s faculty and administrative leadership responded — and the book that revealed the previously unreported reason for the dismissal.

One of the most ambitious histories written about Notre Dame began as a question that came up during lunch among friends at the University Club.

The first two volumes of Being Catholic, Being American, published in 1999 and 2000, add up to more than 1,000 pages. They take the reader from Notre Dame’s founding in 1842 to 1952, when Father Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, became president. A third volume — covering the Hesburgh era — was never completed.

The author of this detailed and extensive narrative on the life of Notre Dame succumbed to cancer before he could finish what he started.

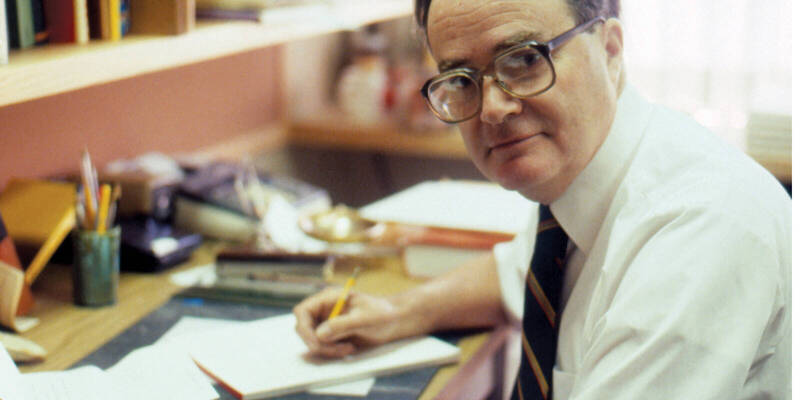

Robert E. Burns was a long-time member of Notre Dame’s history department and a scholar of Anglo-Irish relations in the 18th century. Even though Burns had held key administrative posts in the College of Arts and Letters, few would have anticipated his taking on such a comprehensive institutional history. But his broad-ranging intellectual curiosity and his readiness to plunge headlong into unfamiliar territory were set in motion during that collegial meal in 1987.

Bob often lunched with a group of veteran historians and other old-timers, and on that autumn day, conversation centered on a Chicago Tribune article about the death of Frank McMahon, a former professor of philosophy at Notre Dame who was summarily dismissed from the University in November 1943. McMahon had a national reputation as a Catholic spokesman for liberal causes. When he was unceremoniously cashiered in mid-semester, people — both on campus and elsewhere — assumed the University had caved in to political pressure from conservatives. The result was a firestorm of unfavorable publicity.

One of our lunch time group, M.A. Fitzsimons, a professor of history, remembered the incident vividly. Not only had he known McMahon as colleague in the 1940s, he had personally drafted a letter — to which 29 members of the faculty attached their names — protesting so blatant a violation of academic freedom. The episode itself aroused Bob Burns’ curiosity, and Fitzsimons’ involvement intensified it because Burns’ esteem for his senior colleague in British history bordered on veneration. If this was something Fitzsimons felt so strongly about, Burns wanted to get the full story.

That sparked his initial investigation. But as he plowed into the sources — newspaper accounts and archival documents — the scope of the project kept expanding. For readers to understand the incident itself, Burns had to describe its campus context. And because McMahon’s firing seemed clearly related to his off-campus political activities, it had to be set in the larger context of a nation embroiled in World War II.

The key link between the local and national scenes, Burns soon discovered, was forged in the great debate between “interventionists” and “isolationists” that took place in the two years before Pearl Harbor. For it turned out that Notre Dame had two nationally prominent figures representing diametrically opposing positions. McMahon, an interventionist, argued strongly that the United States had a stake in the battle against Nazi Germany and should provide all aid “short of war” to Great Britain and the Soviet Union.

His opposite number was Father John A. O’Brien, a diocesan priest from Illinois and a newcomer to Notre Dame’s religion department in 1940. O’Brien, already well-known as a writer of popular religious works, threw himself into the campaign to “keep America out of the war,” and soon made himself the most widely known Catholic isolationist in the country.

Working to untangle all the strands of the situation, Burns found himself moving continually backward in time. At some point in the process — which I doubt he himself could have identified precisely — his interest in the McMahon affair ripened into a near-obsession with the history of the University itself. As a result of his enthusiasm for the subject and tireless work in the Notre Dame Archives, Burns didn’t get to McMahon’s firing until Volume II of his history. But he didn’t skimp when he finally got there, devoting eight of the book’s 13 chapters to the affair, plus a chapter of detailed background on Father O’Brien’s earlier career.

Fortunately, Burns’ fondness for detail was usually balanced by an informal narrative style that could hold the reader’s interest and keep the story moving. In Volume I, for example, he dealt with the first 50 years of Notre Dame’s history in one chapter. However, it was the 20th century that really fascinated him. As a result, it took him 14 chapters to cover the years between Father Sorin’s death in 1893 and Father John F. O’Hara’s becoming president in 1934.

The 500-plus pages of Volume I provide full coverage of curricular issues and other academic developments. But the title Burns chose for his book — Being Catholic, Being American — reflected his primary interest in Notre Dame’s public history, the people and events that related the University to the larger society. Football and Notre Dame’s brush with the Ku Klux Klan were particularly relevant from that angle, and he explored both topics in depth.

Volume II begins with what Burns regarded as a major turning point in Notre Dame’s history — Father O’Hara’s taking the reins as president in 1934. Although he is better known in campus folklore for personally yanking books he considered salacious from the shelves of the University library, O’Hara also understood that Notre Dame had to improve its academic standing by promoting scholarly research. To reach this goal he encouraged his younger confreres in the Holy Cross community to pursue advanced degrees; he hired a number of well-credentialed young lay professors; and he recruited a cadre of outstanding European scholars fleeing political and religious persecution in Europe.

Among the group of promising lay professors was Francis E. McMahon, a devout Catholic and, in philosophy, a thorough-going Thomist. His firing in 1943 is the centerpiece of Volume II, and Burns devoted 270 pages to its complexities.

He also revealed a well-kept secret — and suffice it to say that the public relations disaster which McMahon’s firing brought on would have been much worse had the full story come out in 1943. For it was not the influx of mail from political conservatives that triggered McMahon’s dismissal, as the public believed. It was a directive from Rome.

In one of his many off-campus speeches, McMahon offended the government of Spain by referring to the regime of General Francisco Franco as “Fascist.” That prompted a protest by Spain to the papal secretary of state, who passed the matter along to the Apostolic Delegate in Washington. That official added a few of his own complaints about McMahon when he instructed Father J. Hugh O’Donnell, CSC, then president of the University, to silence his maverick professor.

Father O’Donnell considered himself bound in religious obedience to do just that — and without, of course, revealing that he was doing so under orders from the Vatican. Such was the hidden history of the McMahon affair, made known 57 years after the event by Bob Burns.

Even without public knowledge of the Vatican’s involvement, the result of McMahon’s firing was a serious setback to Notre Dame’s reputation as an institution of higher learning. And the embarrassment of that academic black eye was still fresh in everyone’s memory when Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, faced a somewhat similar, but much less serious, faculty disturbance in the early months of his presidency.

When the McMahon affair exploded, Father Hesburgh was in Washington, D.C., finishing his doctoral studies in theology. He returned to the campus in 1945 and played an active role in the administration of Father John J. Cavanaugh, CSC, Notre Dame president from 1946 to ’52. That was the last period dealt with in the pre-Hesburgh Volume II, and Burns shows how — first as head of the religion department then as executive vice-president — Father Hesburgh displayed the vision and leadership that made his appointment as Cavanaugh’s successor all but inevitable.

Father Hesburgh’s determination to raise Notre Dame’s academic standing is the leading theme of Burns’ unfinished Volume III. Burns emphasizes throughout that the new president aimed at making Notre Dame a university ranking among the best in the nation. That goal might, however, have been sidetracked at the outset by another potentially damaging academic freedom controversy.

When Hesburgh took office in the summer of 1952, the presidential race between war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican, and Illinois Governor Adlai E. Stevenson, a Democrat, was beginning to take shape. As it heated up in the fall of the year, a group of liberal-minded professors at Columbia University released a public letter endorsing Stevenson’s candidacy. This was followed by two letters from Brown University, one pro-Stevenson, the other pro-Eisenhower.

These precedents inspired similar action by Stevenson supporters at Notre Dame. Frank O’Malley, the legendary professor of English who was also a Democratic precinct captain, drew up a pro-Stevenson testimonial signed by 65 members of the University faculty. It contained the standard disclaimer that the signers were speaking as individuals and not as representatives of the University. That distinction was hopelessly blurred when the Stevenson forces used what they called the “Appeal from Notre Dame” in paid political advertisements all across the country — and when the former chairman of the Democratic National Committee referred on network television to “the Notre Dame Petition.”

Hesburgh, who had not been informed of what was afoot, was immediately deluged by protests from Eisenhower supporters and others who objected to this departure from the University’s traditional policy of strict neutrality in partisan political affairs. Although surely more than a little annoyed at being blindsided by the faculty letter, the new president’s reaction was marked by prudence and moderation.

First, he and a prominent member of the University’s lay advisory board made public statements denying that Notre Dame had officially endorsed either political candidate and condemning the Stevenson campaign for the misleading way it exploited the faculty letter. Then Hesburgh addressed the campus community in a separate statement that affirmed the right of faculty members to speak out on public issues as private citizens but sharply criticized their having done so in a way that involved the University.

Where did this leave the faculty? To be censured for “involving the university” when they had explicitly stated that they were not speaking for the University seemed to mean they could not speak out at all without running the risk of disciplinary action by the administration.

To many on the faculty, this amounted to saying that a private citizen effectively lost the right to free speech by becoming a professor at Notre Dame.

Sensing the depth of faculty disappointment and anger generated by this formulation of the issue — and no doubt remembering the McMahon imbroglio — Hesburgh composed a second letter to all the members of the faculty. In it he restated their right to speak out on public affairs in language that eliminated any ambiguity left by his first statement on the subject. But, he added, recent experience demonstrated that statements made by people at the University were easily misunderstood as statements of the University.

Noting that this was an ongoing problem, Hesburgh here executed what Burns calls a “dramatic démarche” by proposing something new in policy-making at Notre Dame: He called upon the faculty to assist him in finding a mutually satisfactory way of handling such matters in the future. As a first practical step in the process, he appointed an eight-member “Presidential Advisory Committee.” This body, composed equally of signers and non-signers of the Stevenson letter, was to review all aspects of the affair in consultation with their colleagues and make recommendations about procedures to be followed in the future.

The committee did its job conscientiously, creating a substantial file. Its report to the president was not, however, made public. In fact, that report was probably never seen by any faculty member other than those who drew it up — until Burns unearthed it in the archives of the University. From his account, it seems the committee failed to come up with concrete policy suggestions. What its report did do was document the intensity of faculty feeling about their right to speak freely on public issues — while conceding that some limitation on academic freedom was appropriate in respect to Catholic teaching on faith and morals.

Since this represented the consensus already existing among the faculty, and since Father Hesburgh got the message, what was to be gained by making the report public? By the time the committee delivered its report early in 1953, the election was long past, Eisenhower was president and the general feeling on the campus was, as the committee put it, “the Stevenson incident as such is dead and should be allowed to remain so.” In these circumstances, publicizing the report promised to do more harm than good, and it was quietly filed away.

Burns gives Hesburgh high marks for the restraint and good judgment he showed in averting a prolonged academic freedom controversy that could have done serious damage to his plans for upgrading Notre Dame’s reputation as an institution of higher learning. Burns also makes clear that the new president “got the message,” for he made regularizing the faculty’s status in the University one of the first items of business on his agenda of reform.

Besides the Stevenson-letter affair and the creation (and later revision) of a faculty manual, the draft version of Burns’ Volume III touches on all aspects of Notre Dame’s history from 1952 to the early 1970s — curricular reforms, successful fund drives, new buildings, the tumultuous 1960s, the shift to a lay board of trustees, the introduction of co-education, and, of course, the ups and downs of the football program.

In all this, Burns recognizes the crucial importance of Hesburgh’s leadership. And Burns drives home the point in a striking formulation — Father Hesburgh, he writes, was at first known as the president of Notre Dame, but within a few years Notre Dame was known as the university of which he was president.

Unfortunately, Volume III of Being Catholic, Being American was never published because Burns was battling cancer the whole time he struggled to complete the final volume, now in the University Archives. Sadly, he died in February 2010, leaving behind a rough draft of some 280 typed pages — unfinished and needing polishing throughout. The last section, a catch-all “Epilogue,” was most obviously written in haste. Clearly Bob Burns — my friend of 50 years — could feel the end approaching.

Philip Gleason, a Notre Dame professor emeritus of history, is the author of Contending with Modernity: Catholic Higher Education in the 20th Century, and other works. In 1999, he was awarded Notre Dame’s highest honor, the Laetare Medal.