After last year’s contentious presidential election, the Associated Press sent a correspondent to Appomattox, Virginia, where Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee met in 1865 to bring an end to the Civil War. Near the beginning of the dispatch focusing on just some divisions separating Americans during the 2012 campaign, the reporter offers a series of descriptive phrases: “Red or blue. Left or right. Big government or small. Tea party or Occupy. Ninety-nine percent or 1. Employed or out-of-work. Black or white or brown.”

Beyond these categories, you could add some social or cultural differences with their own sharp edges: Rural or urban. Coast or heartland. Junior or senior. Church-going or nonreligious. Married or single. Straight or gay. The list goes on, and what makes all these divisions significant is their internal coherence in shaping an identifiable, differentiated group. It’s almost as though separate tribes now populate the country, each with a definite outlook in conflict with the opposite viewpoint or condition.

This current clustering reflects a broader cultural trait that’s been evolving in America during the past three decades. Advances in communication — semantically illustrated by following the movement from “broadcasting” to “narrowcasting” to “slivercasting” — gave rise to the niche or audience segment most receptive to a specific message. Translate that principle to likeminded people who use the new technology of social media (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc.), and you move beyond a niche to the mobilization of individuals with definite characteristics or objectives.

What’s missing in this new environment is the broader, common experience that contributes to a sense of unity with national scope.

Divisions are, of course, nothing new in America, with the Civil War our most tragically obvious consequence of those that existed in the 19th century. A century later, the 1960s brought differences to the fore again, and the author Garry Wills traveled throughout the United States to write a book-length chronicle with the foreboding title The Second Civil War.

Interestingly, in its first edition of 1970, Time surveyed the upheavals of the previous year —dissent over the Vietnam War, racial conflict in cities, rebellion on college campuses — and named “The Middle Americans” as the magazine’s “Man and Woman of the Year.” The cover story makes a case for its choice by celebrating the traditional values under assault from so many sides: “Above all, Middle America is a state of mind, a morality, a construct of values and prejudices and a complex of fears. The Man and Woman of the Year represent a vast, unorganized fraternity bound together by a roughly similar way of seeing things.”

During the 1960s, the basic tension animating the period involved the friction between a set-in-its-ways establishment and what was termed “the counterculture,” with its new ideas about race, gender, personal behavior and all the rest. Amid the decade-long actions and passions, separate purposes seemed to mark each side.

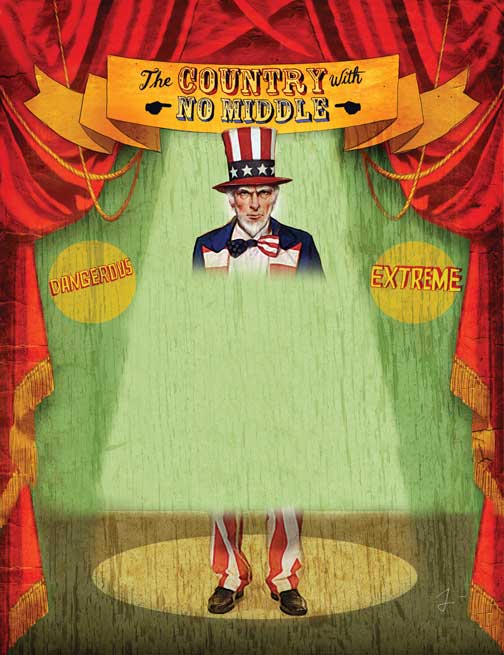

What’s striking today, four decades later, is the absence of an easily identifiable “middle America,” even one with prejudices and fears. To talk of a “state of mind” that might provide a metaphorical anchor or sense of community sounds more quaint than relevant to our time.

More important, the mention of any semblance to “middle America” confronts the reality that it is increasingly difficult to locate a, let alone the, middle in critical dimensions of national life. The mainstream is less recognizable because individual tributaries now collect more followers, receive greater attention and exert unprecedented influence.

As Exhibit A, when considering America’s vanishing middle all you have to do is take the related realms of politics and government. In recent years, partisanship between Democrats and Republicans has escalated to hold-your-ground-at-any-cost polarization, making compromise less an operating principle and more a suspect maneuver. With each party firmly planted on either side of the political spectrum, the center is a no-person’s land — and problems never seem to get resolved.

Just how polarized is American politics today?

Political columnist Ronald Brownstein surveyed contemporary Washington and, like Wills before him, thought the depth of the divisions deserved appropriate dramatization. He called his study The Second Civil War, adding a precise subtitle: How Extreme Partisanship Has Paralyzed Washington and Polarized America.

Vigorous partisanship is fundamental to any vibrant democracy. Competing ideas provide the sparks of civic action. It’s when partisanship veers to the extreme that stasis results and the game changes — from, if you will, bridge to solitaire.

Brownstein isn’t alone in offering a warning. Writing in The New Yorker early last year, Ryan Lizza observed, “In Washington, the center has virtually vanished.” He supported this conclusion with research findings of political scientists who measure ideological performance in Congress.

“In the House, the most conservative Democrat, Bobby Bright, of Alabama, was farther to the left than the most liberal Republican, Joseph Cao, of Louisiana,” wrote Lizza. “The same was true in the Senate, where the most conservative Democrat, Ben Nelson, of Nebraska, was farther to the left than the most liberal Republican, Olympia Snowe, of Maine.”

Lizza goes on to remark that “both the House and the Senate are more polarized today than at any time since the eighteen-nineties.” Tellingly, not one of those four members of Congress continues to serve in office today. Both Bright and Cao suffered defeats at the polls, while Nelson and Snowe decided to retire rather than seek re-election.

Analyzing all Congressional votes during 2011, the nonpartisan National Journal rendered this summarizing judgment, “Polarization remains endemic. Lawmakers march in lockstep with their party. Heretics are purged.”

In today’s political environment, the “heretics” are moderates, those inclined to work across party lines on legislation. When Snowe decided not to seek re-election in early 2012, it was a clear sign that the center was shrinking within what’s often called “the world’s most exclusive club.” In one interview after her announcement, the three-term senator, who also served 16 years in the House, lamented, “There’s no longer political reward for consensus building.”

Several intertwining factors make Washington a difficult place to conduct the public’s business, as the tortured bargaining over taxes and spending during the “fiscal cliff” melodrama illustrated a few months ago. At one point, with talks stalled and prospects for a comprehensive agreement out of reach, West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, a Democrat, spoke for more than himself when he said, “Something has gone terribly wrong when the biggest threat to our American economy is the American Congress.”

Describing why accomplishing anything now seems a Herculean task — analysts consider the 112th Congress that ended on January 3 of this year the “least productive” on record — Gerald F. Seib in The Wall Street Journal sketched out some reasons. “Conservative Democrats are an endangered species, and liberal Republicans are essentially extinct,” he wrote.

“Increasingly precise congressional redistricting designed to keep Democrats in safe Democratic districts and Republicans in safe Republican ones has only reinforced the pull away from the center. The tendency is furthered by each party’s financial machinery and outside megaphones, which are dedicated to enforcing party discipline.”

So where’s the middle ground in this political and communications landscape? Hyperpartisanship keeps office holders apart and reluctant to reach out to anyone on the other side. Then, the rise of aptly termed “wedge issues,” explicitly intended to divide voters (such as same-sex marriage, gun control and school prayer), exacerbates the situation and can lead to single issue or polarized voting.

Making matters worse is the current emphasis in elections to use virtually any means to destroy one’s opponent in winning an office. In many races during the 2012 campaign cycle, victors emerged with both bloody noses and dirty hands as a result of all the attacks that swamped the airwaves — and sickened voters.

The borders between politics and government are notoriously porous.

However, when the conduct of governing is likened to “a permanent campaign,” as political analysts now claim, this means electioneering tactics become fair game for use by either side in debating legislation or an appointment requiring confirmation. A middle ground of possible agreement is more elusive when each party approaches a subject or individual as a pre-planned pitched battle.

It hasn’t always been this way. Back in 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law after Republicans in greater percentages than Democrats supported the legislation in both the House and Senate. By contrast, in 2010, the Affordable Care Act, championed by President Barack Obama, became law with his signature — and the votes of just Democrats in both Congressional chambers. Not a single Republican in the House or Senate voted to approve the bill establishing health care coverage in the United States.

Between the tumult of the 1960s and today, American politics experienced identifiable sea changes. The parties became more regional and ideological, with Republicans most prominent in the South and Southwest, and Democrats dominant in the Northeast and on the West coast. Conservative Southern Democrats and liberal Northern Republicans vanished.

In this altered environment, battles in Washington assumed new-found intensity. Two seemingly unrelated events that occurred during the summer of 1987 signaled the no-holds-barred approach and, in retrospect, represent two partisan sides of the same political coin.

In July of that year, Robert Bork had been selected by President Ronald Reagan to be a Supreme Court Justice, and Democrats decided to kill the nomination. Charges that the former Yale law professor and federal appeals court judge was “a right-wing loony” and “extreme ideological activist” were repeated often — and a new verb was born.

According to no less an authority than the Oxford English Dictionary, “to bork” means “to defame or vilify [a person] systematically, especially in the mass media, usually with the aim of preventing his or her appointment to public office.”

At exactly the same time Bork was being stopped by the Democrats — and it is less a coincidence than a convergence of similarly motivated and malevolent intentions — Newt Gingrich, then a back-bench Republican member of Congress, started plotting to bring down Speaker of the House Jim Wright, a Democrat. In Gingrich’s memoir, Lessons Learned the Hard Way, he offers “August 1987” as the moment when he began his planning, and then he kept pushing as forcefully as he could for removal. Not quite two years later, on June 6, 1989, Wright was replaced as speaker, the first to resign amid scandal.

What’s come to be known since then as “the politics of personal destruction” contributes to the ferocity of partisanship and the resultant polarization. With increasing frequency, Democrats and Republicans keep to themselves, rarely venturing from whatever the party line might be.

How divided politically has America become?

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy that ravaged the East Coast last October, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, a Republican, received a blizzard of criticism from his party for praising the response of President Obama and his administration in dealing with the destruction. The plainspoken Christie committed a sin of candor by commending an incumbent Democrat for cooperation between his state and the federal government.

Within Republican Party ranks, Christie quickly became persona non grata, a target of ideological talk-show hosts and columnists who view any traffic between the two parties as nefariously consorting with the enemy. Even the long-term implication of what the governor said and its impact should he decide to run for president in 2016 received airing. “It hurt him a lot,” one GOP stalwart in Iowa told The New York Times. “The presumption is that Republicans can’t count on him.”

Although partisanship occurs most visibly within Democratic and Republican circles, the people at large are changing along with their elected officials and the party workers. In a study involving more than 3,000 respondents that was conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Washington Post prior to last year’s election, the number of “strong” partisans measured in the survey markedly increased. During the past 14 years, the percentage of Democrats and Republicans identifying themselves as definitely partisan grew from less than half to almost two-thirds in each case.

That level of partisanship intensity was reflected in the November balloting, according to exit polls. Obama captured only 6 percent of Republican votes and Mitt Romney 7 percent of those cast by Democrats. True independents, the elusive as well as prized swing voters, still exist, but their number shrinks at the same time the middle of our politics becomes smaller.

When Obama emerged as a national figure with the keynote address he delivered at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, he emphasized a message of unity: “[T]here’s not a liberal America and a conservative America — there’s the United States of America.” What he said struck a chord not only with Democrats but also with others weary of perpetual conflict between “red” and “blue” America.

However, the Obama who developed as a centrist from 2004 through his election as president in 2008 stands in stark contrast to the public’s perception of him during his first term in the White House. Obama couldn’t bridge the current political divide — and his campaign for re-election in 2012 was entirely different from four years earlier. This time Obama knew what it took to win, and he made no real effort to project himself as someone wanting to straddle “red” and “blue” America.

But our politics and government don’t operate in a vacuum. Today’s protean partisanship is nurtured and sustained by media outlets that thrive on opinion and argument rather than facts and reporting.

At the same time politics became more polarized, new communication technologies challenged mainstream sources of information — and decreased the audience and influence of traditional outlets. Michael Gerson, a columnist for The Washington Post who served as President George W. Bush’s chief speechwriter, described the current mediascape and its political role:

“Because of the ideological polarization of cable television news, talk radio and the Internet, Americans can now get their information from entirely partisan sources,” Gerson observed. “They can live, if they choose to, in an ideological world of their own creation, viewing anyone outside that world as an idiot or criminal, and finding many who will cheer their intemperance.”

Since the 1990s, as media proliferated and targeted their messages for specific audiences based on demography or ideology, the significance of a common, shared pool of data means much less for the simple reason that fewer people are swimming in that pool. Sources featuring political opinion strengthen partisan viewpoints and never mention the possibility of bringing different sides together.

During the 2012 campaign season, a new phrase began appearing in political discourse to describe this new communications culture. Observers termed the charges and countercharges of the presidential candidates as illustrations of “post-truth politics.” With so many media sources fixated on distributing partisan opinion instead of verified information, assertions of dubious accuracy are now circulating unchallenged and seeding themselves in public thinking.

At the end of last year’s White House race, Politifact, a nonpartisan project to evaluate truthfulness in political rhetoric that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2009 for national reporting, found that of the 453 statements by Obama that were analyzed, 45 percent could be classified as true or mostly true. The majority (55 percent) fell into the categories of half true, mostly false or false. For Romney’s 202 examined statements, 31 percent were judged true or mostly true, with the rest (69 percent) as either misleading or false.

High school civics classes always teach that a well-functioning democracy depends on an informed citizenry. What happens, though, when large portions of the public rely on sources propelled more by a partisan viewpoint than a rounded, factual account? It’s little wonder that three weeks before Election Day, Time devoted its cover story to “The Fact Wars,” posing the dispiriting question “Who is telling the truth?”

In one of his more arresting aphorisms, Friedrich Nietzsche warns: “Convictions are more dangerous enemies of truth than lies.” As polarization in politics becomes more pronounced —with assistance and amplification coming from accomplices in the media — it’s increasingly difficult to arrive at consensus (or even swallow-hard compromise) when convictions approach the stature of a belief system. Truth, too, takes a backseat in this new political-media ecosystem.

It’s one thing for a person to feel trapped in the crossfire of partisan messages, driven more by fury than the sound of rational discourse. It’s another to worry that the problems politicians can’t seem to resolve are, at least in part, responsible for jeopardizing someone’s socioeconomic place or standing in today’s America.

Globalization, technological innovation, financial chicanery and other forces toss a large monkey wrench into established work patterns, disorienting millions and creating fear about the future. This anxiety is felt most acutely by those in the middle class, which for decades has served as the nation’s bulwark.

Last August the Pew Research Center on Social and Demographic Trends released a 138-page study, “The Lost Decade of the Middle Class,” as statistically stark as any partisan pronouncement from the left or right. While those in politics have moved away from the center, the percentage of people defined as being in the middle class also declined — and alarmingly so.

According to this methodical analysis, between 1971 and 2011, the number of middle Americans dropped from 61 to 51 percent. The past decade proved especially destructive, with median household income falling from $72,956 in 2000 to $69,487 in 2010, and median net worth plunging from $129,582 to $93,150.

What Pew calls “the hollowing of the middle” increased both the “upper-income tier” (from 14 percent in 1971 to 20 percent in 2011) and the “lower-income tier” (from 25 percent in 1971 to 29 percent today). The study bases its findings on a three-person household with an income range between $39,418 and $118,255.

Numbers, however, tell just a fraction of the story for the majority of Americans who seem to be on an economic treadmill, taking them nowhere without strengthening their position for the future. To be sure, the Great Recession, which lasted from the end of 2007 through the first half of 2009, proved a chief culprit in the drop of household wealth and mounting personal doubt. But a gnawing fear took root throughout the decade in the thinking of those feeling squeezed at the middle.

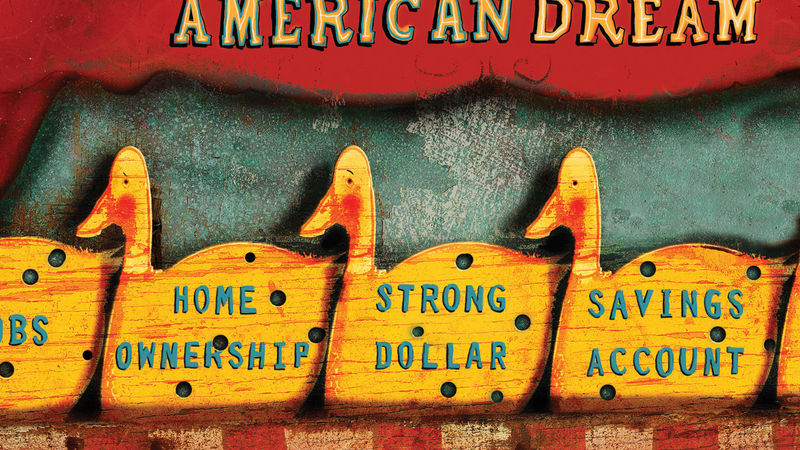

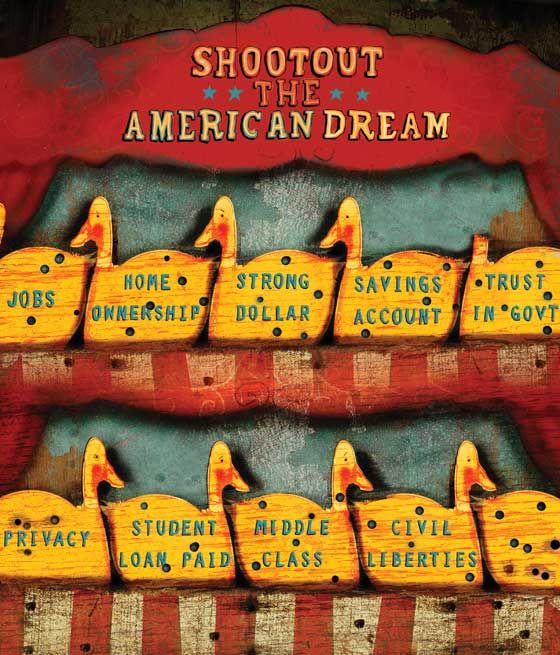

One of the nation’s most cherished ideals, the American dream, began to seem too remote, as people struggled to keep a job, buy a home, pay school tuition or just meet day-to-day obligations. As different segments of the economy suffered downturns, working to provide a more secure and prosperous opportunity for the next generation’s tomorrows — an essential element of this shared reverie — proved less important today than simply scraping by.

Last year alone, this middle-class angst brought two sobering yet revealing books: The Betrayal of the American Dream by Donald L. Barlett and James B. Steele, and Who Stole the American Dream? by Hedrick Smith.

A refrain of all this attention to the middle class and threats to the American dream is that the distance between the “haves” and “have-nots” keeps widening, as those with greater wealth discover ways to enhance their position. Whether it’s influencing tax policy, shipping jobs overseas or reducing pension payouts, economic profits come with a human price. For many midlevel employees, wearing white, blue or pink collars, corporate decisions produce individual consequences that often lead to a broader impression: the nation’s middle-class backbone is getting weaker.

For last year’s Pew study, researchers asked “self-described middle-class respondents,” enduring more difficult straits than a decade ago, who deserved the most blame for recent economic problems. Congress, that bastion of polarization and gridlock, was the choice of 62 percent for “a lot” of the culpability, followed by banks or financial institutions and large corporations.

The inability of Congress to tackle and solve long-term concerns leads people to think that work vital to their own welfare is not being transacted. Moreover, the legislative branch of government, consumed with partisanship that impedes action, also ranks lowest among institutions when surveys inquire about trust and confidence.

The declining fortunes of the middle class assume political significance and receive continuing lip service for the simple reason that there are more votes in this economic stratum than either above or below it. Worry about the future and more pronounced economic divisions comes into bold relief by considering recent data.

Last summer The Wall Street Journal reported about pay disparity in the United States: “Total direct compensation for 248 CEOs at public companies rose 2.8% last year, to a median of $10.3 million, according to an analysis by The Wall Street Journal and Hay Group,” wrote Leslie Kwoh. “A separate AFL-CIO analysis of CEO pay across a broad sample of S&P 500 firms showed the average CEO earned 380 times more than the typical U.S. worker. In 1980, that multiple was 42.”

Evaluating similar data for 2011, the Associated Press included additional comparative statistics and context in a dispatch that appeared in late May. “The typical American worker would have to labor for 244 years to make what the typical boss of a big public company makes in one,” the wire service reported. “The median pay for U.S. workers was about $39,300 last year. That was up 1 percent from the year before, not enough to keep pace with inflation.”

As the pay gulf widened, so, too, did the distance between the boss and the average employee.

While CEOs worried about sheltering income from taxes or made sure their parachutes were truly golden, workers kept looking over their shoulders to see whether a move to downsize might affect them — and jeopardize their place in the middle class.

What’s called “the great divergence” captures this new reality for people in America’s economic center. They don’t begrudge economic success in our free-market system, but many view themselves as closer to the lower tier than the upper one. This apprehension about the future comes primarily from what they remember about the past. For anyone who grew up between 1950 and 1975, a place in the middle class meant stability and security. Strength came from numbers and a shared outlook of progress and optimism about the years ahead.

Today’s constant fretting about what it will take to keep up with bills and maintain a middle-class lifestyle is more than nostalgia for an earlier, less economically divided time. An egalitarian temperament is a national characteristic with deep roots in the country’s soil. Indeed, the metaphor of the American dream was first formulated by historian James Truslow Adams in 1931 during the Great Depression. At that time, amid bleak circumstances, a collective sense that “we’re all in this together” created similar footing, common ground, for people to occupy.

To show the long tradition of this way of thinking, a century before Adams coined his phrase, the young Frenchman, Alexis de Tocqueville, toured the New World and wrote about his visit in Democracy in America. The first two sentences of his introduction set the foundation for the two hefty volumes that follow: “No novelty in the United States struck me more vividly during my stay there than the equality of conditions. It was easy to see the immense influence of this basic fact on the whole course of society.”

As the middle class declines in “conditions” and becomes smaller in number, this impression of equality is threatened. An “us versus them” mentality develops, and competition rather than cooperation takes precedence. Rungs on the American ladder — a fair chance, access to opportunity, the pull of upward mobility, promise for the next generation— seem unable to support everyone wanting to make the climb.

The “hollowing out” of the middle class is taking place at the same time as the flight from the middle in politics, the media, and other aspects of American life. In his poem “The Second Coming,” William Butler Yeats describes a world where extremes hold sway without the benefit of an anchoring center:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world. . . .

In contemporary America, we somehow need to find a new divining rod to locate a center or middle ground that can, indeed, hold and effectively handle problems demanding attention. This is especially true in the realm of politics and government because extracting the poison of polarization might bring consensus on several vexing issues to help not only strengthen the middle class but also dial down the decibel level of media discourse. Our body politic would be more fit.

Simplistic as it might sound, it’s really a matter of developing a greater sense of proportion with a wider angle of public interest that combines viewpoints across the spectrum of thought. America’s founders drew inspiration from Aristotle and his concern for seeking “the golden mean” between extremes to achieve “the happy life.” Indeed, our governmental system of shared powers, checks and balances builds on Aristotle, stressing the necessity of compromise and moderation.

The trick, of course, involves seeking resolutions acceptable to different outlooks and approaches. Where’s a potential meeting point? How can we arrive at common ground? What will it take to occupy a sensible center?

Such questions deserve answers when so much is at stake. With the pursuit of middle-class security, not to mention happiness, in jeopardy for so many, the urgent need to look beyond differences and blunt sharp-edged divisions couldn’t be clearer.

In his first message to Congress as president in 1901, Theodore Roosevelt said, “The fundamental rule in our national life — the rule which underlies all others — is that, on the whole, and in the long run, we shall go up or down together.” Roosevelt understood the centrality of a nation’s cohesion. Recognizing that larger purpose today involves looking beyond whatever keeps people apart and discovering what might bring them together.

Near the end of Michael J. Sandel’s recent book, What Money Can’t Buy, the Harvard professor argues: “Democracy does not require perfect equality, but it does require that citizens share in a common life. What matters is that people of different backgrounds and social positions encounter one another, and bump up against one another, in the course of everyday life. For this is how we learn to negotiate and abide our differences, and how we come to care for the common good.”

Our divisions — in politics, culture and economics — keep likeminded people too much among themselves and removed from an agreed-upon public square near the middle of their respective positions. Finding a way to reach common ground among disparate groups can, ultimately, lead to uncommon accomplishment and, possibly, even the common good. Though the first step might be tentative and seem treacherous, it’s a necessary one for all of us to try to take.

Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor of American Studies and Journalism at Notre Dame, where he directs the John W. Gallivan Program in Journalism, Ethics & Democracy.