Andrew Hadley is a fish fixer. As the heir-apparent to the Hadley Company, an international fish-processing and import-export business, he steps in when a New England casino calls on a Thursday and says it needs 600 pounds of whitefish for the weekend. He loads the truck himself, drives it down to the casino and gently reminds the buyers to place their orders a little earlier in the week next time.

When he’s not attending to the unexpected, Andrew does a little bit of everything at the Hadley Company, which was founded by his father and grandfather in 1986 and owns fishing boats that ply the seas of the North Atlantic and North Pacific from home bases in Iceland, Norway, China and the Faeroe Islands. He has made cold calls and restaurant visits in his official capacity as a sales representative; he has handled the company’s clerical work; he creates promotional materials and works the crowds at food shows.

- Related articles

- Much more than school

- Molarity Redux: The Tuition Bubble

These days he spends much of his time tasting product before it leaves the company’s Marion, Massachusetts, warehouse. When the finished fish arrives from China, where it is sent for processing, he pulls out samples and cooks them in every way imaginable: frying, searing, boiling, microwaving. When the final product meets his satisfaction and exits the warehouse door, it might end up on your grocery store shelf, in the buffet line of a New England casino or on the table of your local restaurant.

Hadley has been working at the company since high school, and he has a job there as long as it exists. But that didn’t stop him from enrolling in college right after he finished high school. In the spring of 2013, his final semester of college, every Tuesday and Thursday morning he would be in my classroom, engaging in discussions with his classmates and me about such controversial topics as affirmative action or gun control as part of the coursework for Argument and Persuasion, an upper-level writing seminar.

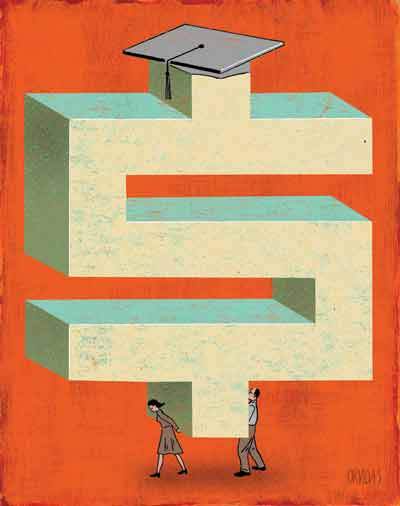

As we sat talking in my office one day after class, and I learned about his work outside of his studies, I wondered why Andrew had bothered to attend college at all. The full-boat payment at Assumption College in Worcester, Massachusetts, for the 2012-13 academic year, including tuition and room and board, rolls in at just under $50,000. With a job waiting for him from the moment he was born, what did he stand to gain from shelling out such a whopping sum of money for four years running?

When I posed this question to Andrew, his responses resonated with humor and good sense.

First and foremost, he said, college exposed him to the viewpoints of others and helped him find his place in the world beyond his small hometown. He identified that as the most important value of his college experience.

He also mentioned specific courses that would help him in his future career, including a few in marketing and management in which he was introduced to concepts he brought back to the company and tried to implement. He noted as well some courses he had taken in graphic design that helped him create or revise promotional materials for food shows.

The final point he made, though, seemed difficult for him to articulate.

“Getting the degree is important to me and my family,” he said, noting that his parents are both graduates of highly ranked universities. “It means something. I didn’t need to get this. My dad said I didn’t have to, but it gives a validity to what I’m doing. And if it doesn’t work out at the company, it gives me better opportunities to do something else.”

After he left, I thought about what he had told me. Most of us send our children off to college — as I will be doing for the first time this fall — expecting them to gain a world-class education that will enrich their lives and careers. Andrew is as thoughtful as any student I have encountered, but he could point to only a handful of his 40 classes that would enrich his career. Beyond that, the reasons he articulated were mostly related to socialization and accreditation — he learned about himself, and he earned a degree.

These are certainly valid reasons to attend college, and I suspect most graduates would put them on their list of payoffs for a college education. But are reasons like these enough to justify today’s college prices, which are pushing toward the $60,000 range not only for students at elite colleges and universities but also for those attending private institutions at second- and third-tier levels?

The more I thought about Andrew’s story, the more I began to wonder: Was Andrew making a good investment? Even if he was, where did all of that money he was investing into his college education actually go? Why was his college education so expensive?

The high costs of a college education

Tuition, room and board, and personal expenses will tally up to just a hair over $60,000 at Notre Dame for the 2013-14 academic year. You’ll save yourself $10,000 or $15,000 by sending your child to a smaller, regional college like the one Andrew Hadley attends. Should you choose to send your child to the local state university, thinking to save even more money, you’ll still find yourself shelling out more than you might expect. In my home state of Massachusetts, tuition at our flagship state university comes cheap, at just under $2,000 per year. But tack on room, board and a vast array of mandatory fees, and you quickly climb back up over $25,000.

It’s hard to find an escape from these big numbers, and, most disturbing for the parents of younger children, the future trend seems clear. “Between 2000–01 and 2010–11,” according to the National Center for Education Statistics, “prices for undergraduate tuition, room and board at public institutions rose 42 percent, and prices at private not-for-profit institutions rose 31 percent, after adjustment for inflation.”

More than a dozen years ago I remember sitting down with a financial planner who told my wife and me that we should plan for tuition prices of around $50,000 per year by the time our children arrived at college age. When he walked out our door, I told my wife I thought he was trying to scare up our business by engaging in some ridiculous hyperbole. If I could remember his name, I would track him down and apologize. He had it exactly right.

The worst part of the price tag of a college education today, at least according to some authors, stems from the speculation that colleges and universities are driving up prices through outdated hiring and labor practices, financial mismanagement, and arms-race spending on amenities like sushi in the dining halls and rock-climbing walls in the athletic center.

You can find this claim articulated in many places, but perhaps nowhere so thoroughly argued as in Andrew Hacker and Claudia Dreifus’ Higher Education? How Colleges Are Wasting Our Money and Failing Our Kids — And What We Can Do About It. In support of their contention, in the chapter “Why College Costs So Much,” the authors cite a number of factors that bear responsibility for escalating college prices:

Faculty pay: “Until the recent financial crash, academic salaries had been rising at a much faster clip than in other occupations.”

Burgeoning staff: “Since 1976, the ratio of bureaucrats to students has literally doubled, contributing to a tandem rise in tuition fees.”

Physical plant: “The colleges are caught in an extravagant amenities race, tripping over each other to provide luxuries, large and small, especially aimed at seventeen-year-old applicants.”

Executive salaries: “Between 1992 and 2008 . . . the salaries of most of the college presidents we looked at more than doubled in constant-value dollars. Some rose closer to threefold.”

These arguments seem so damning because none of the factors cited have a direct impact on what we all hope and envision as the main purpose of attending college: receiving that world-class education to prepare you for a meaningful and successful life. Surely, the argument seems to run, we don’t need million-dollar salaries for presidents or rock-climbing gyms in order to achieve that goal. If institutions of higher education were to strip back on the bureaucracy, reign in faculty and administrative salaries, and withdraw from the amenities arms race, they could return their focus to educating their students and save us all a bundle of money in the process.

This is an attractive argument for two reasons: It gives us a villain (greedy colleges) and a solution (austerity measures). Unfortunately, it does not hold up to close scrutiny. The picture turns out to be far more complicated than Hacker and Dreifus would like us to believe.

Why does college cost so much?

To gain a clearer view of that complex picture, we can turn instead to the work of Robert B. Archibald and David H. Feldman, economists at the College of William and Mary. Their book, Why Does College Cost So Much?, takes an innovative approach to understanding higher education prices by comparing them to the prices of a group of similar industries.

Archibald and Feldman point out, first and fundamentally, that we have to think of higher education as an artisanal service industry which requires staffing by highly educated professionals. Similar industries that spring immediately to mind, and for which they provide comparative data, would include medicine, dentistry and the law. Graph the prices of all of these industries together over the course of the past 70 years, and you will see lines snaking continuously around and between one another but never veering far apart. Since the middle of the 20th century, the prices of medical care, dentistry and legal services have risen in an exactly parallel fashion to that of higher education.

Archibald and Feldman’s explanations for this phenomenon are varied and complex, and best suited for those who went beyond my one semester of economics at Notre Dame in the early 1990s. But consider just one thread — less exciting than throwing firebombs at college presidents but much more firmly grounded in the data.

Over the last several decades, productivity in the United States economy, driven by rapid technological changes, has followed a strong growth path. A good that once required 10 workers to produce can now be made by one worker monitoring a machine. The more well-designed and efficient the machine, the less education or training that one worker needs. As a result, we can produce more of those goods with less cost (saving time and labor), thereby increasing productivity while lowering prices.

Compare this with the services provided by higher education or dentistry. While we certainly have more technologically advanced dental equipment and teaching facilities, we still need a highly educated professional to operate that equipment on an artisanal basis — teachers and dentists cannot simply mass produce their services to increase productivity in the way that a manufacturer can. They perform their work one client or classroom at a time, just as they have always been doing.

In fact, mass production and higher outputs in these industries are usually considered a sign of poor quality. Imagine a dentist who claimed that new technologies enabled him to treat patients on an assembly line, churning them out as quickly as possible. Would you trust your teeth to him? Likewise, which sounds like a better school for your child — the one that promises automated advising and increased productivity by putting her in a class of 10,000 students, or the one which promises a small faculty-student ratio, individual attention and mentoring opportunities?

So while productivity in such service professions as education and dentistry remains essentially stagnant, their costs are constantly rising. Fifty years ago a professor needed a chalkboard and a piece of chalk to teach 20 students in his senior seminar. Now his classroom comes equipped with the latest technology — all of which is expensive to buy and has to be maintained by well-paid information technology specialists — that enables the professor to use a wider variety of teaching techniques to work with those same 20 students. So the costs required to construct a modern classroom have risen as a result of the new technologies the professor uses; the number of bodies in the seats (his “productivity”) remains the same. Rising tuition must cover the difference.

We could certainly save some money by chucking the technology and returning to chalk and blackboards, but do we want that? Wouldn’t you prefer that our future doctors or engineers or financial analysts — or even the quality supervisor of your Friday fish dinner — have access to the latest technologies as they are preparing for their careers? While some outstanding teaching and learning can take place when 20 people are sitting in a circle talking about the meaning of life, some of what we have to teach our students today either requires or can be enhanced by digital technologies. With those technologies, anatomy students can take virtual tours of the human body in today’s science classrooms; writing students can use shared Google documents to co-author stories right in the classroom; art history professors can project images from any museum in the world.

Likewise, consider the administrative bloat that the authors of How Colleges Are Wasting Our Money point to. One area that has seen considerable growth in recent years, they correctly point out, has been in the supply of professionals devoted to working with students who might not otherwise succeed in college. Academic support center professionals, specialists in learning disorders, mental health counselors — all of these have indeed swarmed the offices of college and university campuses in recent years. And, once again, colleges must absorb their salaries without increasing productivity; the jobs of these professionals are designed to help existing students become more successful rather than increase the number of students in the seats.

But imagine the alternative. Without that learning-disorder specialist, your child with dyslexia may never make it through the first semester. Without that counselor, your child with anxiety or depression may not be able to manage life away from home. Without that academic support center, your athletically gifted but academically struggling child might never see graduation. Do we want to close off a college or university education to students like these?

Executive salaries in higher education have certainly risen — but so have executive salaries in most other industries. And the standard of living on a college campus, in terms of technology and amenities, has also certainly risen — but so have all of our standards of living. College students don’t want a return to the days of cinder-block dorm rooms with lumpy mattresses, any more than you want to return to the days of no smart phones, microwaves or cable television.

Such issues as executive salaries and amenities, which critics of higher education like to hold up for scrutiny and critique, are nibbles around the edges of the problem. As long as we continue to want individualized attention for our students, and not mass-produced higher education, prices will continue to rise.

Staring down the numbers

That sensible economic explanation of the problem proves cold comfort, however, when you are staring down the barrel of a college education, as my wife and I are doing.

We have five children. The oldest is 17; the youngest are 8-year-old twins. My wife is a kindergarten teacher. We have roughly equivalent salaries, so I can assure you from personal experience that my salary as a college professor isn’t the main driver behind the high cost of your college tuition. Throw into our income mix some additional money from my writing projects.

We are not poor by any means. We have two cars, live in a nice house, take vacations. My wife and I go out to eat a few times a month. But the amount of money we have saved for college payments for our eldest daughter, who will be entering college this fall, amounts to less than the cost of one year at Notre Dame. The amount of money we have saved for our other four children and their college education? Zero.

Even with five children and two teacher’s salaries, we should have saved more. We are working to get our financial picture in better order and to formulate a plan for putting aside money for the younger children, but that will be a challenge when we are paying for the college costs of our eldest daughter.

One way or another, we’ll get them all through. I will do more writing, and we’ll scale back wherever we can. We will take loans, and I suspect our children will have some loans as well. I will do my best to ensure that all of their loans stay at a manageable level, well below the $27,000 average student loan debt cited recently by Forbes magazine. I can’t yet see how we will make it all work, but I’m enough of an American to believe that I can still save myself by working hard and getting my financial house in order.

But now the time comes to return to our first question: Is it worth it?

The easiest way to answer that question involves sticking with the numbers, and the response could not be clearer: A college education, even at the priciest sticker tag, pays for itself two or three times over during a lifetime of employment.

The best recent data comes from a 2011 report from the Pew Research Center entitled Is College Worth It? The figures laid out in the final chapter, “The Monetary Value of a College Education,” reveal the basic economics. Over the course of a 40-year work life, the typical high school graduate will earn $770,000. Over those same 40 years, a college graduate will earn an average of $1,420,000. Even when we factor in four years of lost productivity for college workers, and the costs of college itself, the average college student will find herself a half a million dollars richer, over the course of her lifetime, than her un-colleged peers.

Dollars are not the only payoff. As the Pew report explains, college graduates gain in job stability as well. “In March of 2010,” the report says, “the unemployment rate of a person without a bachelor’s degree was 11%. The comparable unemployment rate for persons with at least a bachelor’s degree was 5%.” When recession hits, college graduate are less likely to find themselves on the chopping block and less likely to see wage reductions.

Andrew Hadley made this same point to me. If his family’s fish company were to falter in some future recession, his college degree would put him in a much stronger position to find another job. Part of that might come from the degree itself and part from networking opportunities available to college graduates, who are likely to have more connections to successful and employed peers than those who did not attend college.

In any case, the data suggests that if you want to provide your children with the best possible opportunity to lead a comfortable life and to remain employed throughout the unpredictable swings of a capitalist economy, you should send them to college.

Hacking your education

The college experience provides its students with much more than just better income and job stability, as Andrew also pointed out to me. Anya Kamenetz summarizes the functions of higher education in a more systematic way in her book DIY U: Eupunks, Edupreneurs, and the Coming Transformation of Higher Education: “You crack a book or go to a lecture and learn about the world; you go to labs, complete problem sets, and write papers, building a skill set; you form relationships with classmates and teachers and learn about yourself; and you get a diploma so the world can learn about you. Content, skills, socialization, and accreditation.”

But Kamenetz only summarizes these functions in order to pose a radical question: What if young people could find ways of fulfilling these functions on their own, without the traditional institution of higher education — and without the associated sticker price?

In fact, a growing educational movement in the United States is banking on just this prospect. With the increasing availability of online learning resources — from the rise of MOOCs (massive, open, online courses) and free or inexpensive online course materials such as the ones provided by the Khan Academy, TED or iTunes U — it may become possible for learners to pursue their education by constructing a personalized network that connects them to peers and teachers with similar interests, provides them with content and helps them build their skill sets — all without plopping down hefty tuition payments.

The most active proponent of this notion might be Dale Stephens, who founded a movement — and now, ironically, an institution — called UnCollege in January of 2011. Home-schooled for much of his early life, Stephens found himself unsatisfied with his educational experiences during his first year in college. So he dropped out and began planning an alternative.

As Stephens describes it on his website, “The mission of UnCollege is to change the notion that university is the only path to success.” For students who are interested in what the movement calls “hacking their education,” the UnCollege website provides links to hundreds of resources: free and open course materials, learning communities, study apps, tutors and more.

In a twist that should not perhaps surprise us, though, Stephens announced last year that UnCollege will begin offering a more structured educational experience for interested students. For a mere $13,000, students will engage in a “gap year” experience that will include a three-month residency in San Francisco and three months studying abroad. The first crew of academic hackers will begin their UnCollege experience this September.

Stephens can promise his participants three of the four outcomes that students can receive at any institution of higher learning: content, skills and socialization. What he can’t yet promise still carries most of the weight these days, especially when you are knocking on the doors of employers: accreditation. The UnCollege movement, by its very nature, eschews the traditional trappings of degrees and accreditation, and so will have no ability to stamp its “graduates” with that standard seal of approval.

As more and more alternatives to traditional higher education appear, some form of accreditation may yet arise for those who choose to hack their education. It’s difficult to imagine what that may look like, but that doesn’t mean it’s not coming.

Learning from the hackers

Eduhacking may never render traditional academic institutions obsolete, probably because a hacked curriculum depends heavily on resources produced in traditional academic institutions. The UnCollege resource page lists, for example, open courses or materials provided by Stanford, Yale, Harvard and MIT. Indeed, plenty of materials you find available for an online education can be traced back to a faculty member who has taken materials developed for a good old-fashioned college course and made them available online.

But those of us who toil in the fields of the academy should keep an eye on educational innovators such as Dale Stephens, because he may have something to teach us about how learning works — and about how we can help our students learn more deeply.

Ken Bain is the provost at the University of the District of Columbia and the author of a highly regarded book on teaching in higher education, What the Best College Teachers Do, published by Harvard University Press in 2004. Last year he published What the Best College Students Do, which analyzed the results of dozens of interviews he conducted with successful people about their college careers.

One of Bain’s most intriguing findings is that those students who gained the most from college were the ones who saw their time in higher education as the opportunity to answer some deeply held questions or pursue some passionate interest they brought to the experience. He cites the case of one student who came to college with four questions he wanted answered, beginning with “Why does anything exist?” and gaining in complexity from there. That student, driven by his own deep questions, took a holistic approach to his college education, gaining much more than a degree — he took full advantage of every opportunity that was presented to him, always seeking experiences and knowledge that would help him answer his questions.

Too many students, by contrast, come into college without any driving questions or interests behind them. They wander from class to class without any sense of larger purpose, checking off boxes on their degree audits, or they see the whole experience as an expensive means to find friends, earn a degree and get a job. These were the kinds of educational attitudes that nudged Dale Stephens out the door of college. These are the kinds of students who, no matter where they choose to matriculate, are probably paying too much for college.

Eduhackers such as Stephens can help remind us that learning happens most deeply when learners are pursuing their own questions or interests rather than the questions and interests foisted upon them by the institution. Some students may come to college with a strong sense of what they need to know and how college can help them; Andrew Hadley would fall into that category. When he enrolls in a graphic design course, he wants to know how it can help his company grow and succeed, and so his interests drive his learning.

Other students need help in discovering their questions and interests. Required general education courses, often derided by eduhackers, can aid in that process. Future philosophers, economists or scientists may never find their calling without that general education curriculum exposing them to courses they might never think to take on their own. But by and large, and as quickly as possible, we should want our learners to discover their own questions and interests, and provide them opportunities to answer their questions through our courses.

Happily, a strong and growing movement in higher education has begun to think hard about how to reshape curricula in precisely these ways. Spurred on by the work of researchers like Bain, and by the growth of research centers devoted to the improvement of teaching and learning in higher education (such as Notre Dame’s own Kaneb Center for Teaching and Learning, or Harvard’s Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning), higher education has been gradually shifting away from courses in which talking heads lecture to a roomful of glassy-eyed students and toward an array of more interactive and innovative teaching models.

One of the most common phrases you hear these days in the literature of teaching and learning in higher education is the “flipped classroom.” In a traditional higher education course the teacher presents course content to the students during class time, and the student then goes home to solve problems or answer questions or complete assignments. In the “flipped” classroom, by contrast, the student absorbs the course content before coming to class — through readings or video lectures or research — and then comes to the classroom in order to put that content to work: raising questions, solving problems, applying theories, engaging in discussion and debate. The flipped classroom allows faculty to provide guidance to students when they are attempting to put their learned knowledge and skills into practice — precisely when they need it most.

The shift toward such models of classroom practice has been a gradual one; colleges and universities can be sluggish animals, and the traditional teaching models that still exist in many classrooms have a long heritage. Faculty have been lecturing at rooms full of students, after all, since the Middle Ages. It will require a sustained effort of time and will in order to push the majority of higher education faculty into exploring the burgeoning number of alternative teaching models that researchers are presenting to us today.

The work of thinkers such as Ken Bain suggests that this will be time and effort well spent. The closer we move toward a model of education in which students are driven by their own deep questions and interests, the more we will provide students with a learning environment that makes a difference in their lives — and the more we will be offering them an education worth buying.

James Lang is the director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at Assumption College. His most recent book, Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty, will be published by Harvard University Press this summer.