Eds. note: Eleven score and 19 years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty. We might mark the occasion with parades or picnics, bunting and fireworks, beaches or baseball. At its best, it’s a day of traditions and family. Former associate editor Tara Hunt ’12 wrote this essay in June 2013, reflecting on a time when the Fourth of July meant all of the above.

As a kid, my summer always began with cobwebs. Memorial Day weekend we’d make our first trip of the year up to our lake house — a one-room cottage with no cable, no Internet, no real air conditioning — and we would begin by dusting away creepy crawlies and running rotten-smelling, rusty water until it came out clear. We’d pull weeds and pick up sticks and complain about the dreaded task of picking up the goose droppings that dotted the lawn. We’d clean the boat, put in the pier, fill the sandbox with fresh sand. And the entire time we would whine and cry about how we hated the cottage and its ugly wood paneling and its list of chores, how we wanted to go home and play with our friends and watch television and go to the pool and have a normal summer vacation like everyone else.

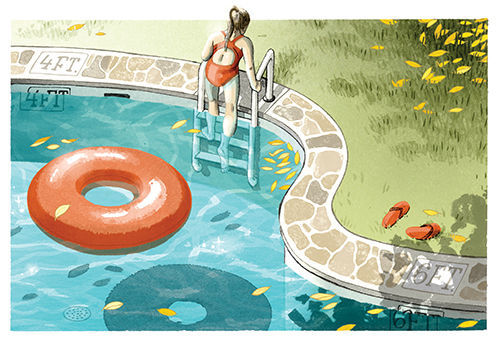

For years, my parents would shove us four pouting children into the car insisting summer weekends were meant to be spent at the lake, together. And they were right. We’d all bicker and fight all week long — he punched me, she took the remote, he’s annoying, she’s a brat — but come the weekends, when we had no one and nothing but each other, we’d set aside our ammunition. During the daytime we’d attach our noodles and floaties together and see how far we could swim out before Mom started yelling, or we’d catch toads in the garden and see how many we could fit in a bucket, or we’d laugh so hard that we’d let go of the tube being dragged behind the boat and go skipping across the water like pebbles. Then in the evenings we’d sit down and peacefully play cards together for hours, forgetting that we fought nearly every other minute of our lives.

Despite the fun we had once we were there, our weekday complaints persisted. We joined sports camps and got summer jobs and started going to the cottage less and less often. And when we were there, the togetherness withered once friends started joining us more regularly and a satellite dish was installed and a loft bedroom was added to give us more space.

This year, the Fourth of July is upon us and we have yet to clean the annual cobwebs. Independence Day was once a second Christmas for us: We’d run around in our swimsuits all day, swimming and sunburning, hang streamers on the boat for our lake’s annual boat parade, eat ribs and corn from the grill and s’mores from the fire pit, watch fireworks from a pontoon rocking in the middle of the lake. It was a day spent entirely outdoors, a day spent together. But this year we’re not even certain the six of us can be in the same state, let alone the same boat watching fireworks.

And the cottage, the place of my childhood memories, the foundation of my friendship with my siblings, is for sale. True, we need less coaxing to spend time together nowadays, but the consistency, the routine, the guarantee of our summer family time is no more.

It’s indicative of the phase we’re entering into — where we make time for new, individual families, and new, individual traditions. But letting go of a place that has been a constant in our lives for 20 years now is difficult and uncomfortable. Letting go of a place that brought us all together, even if it was small and cramped and had only one, persnickety toilet and lots of little critters, is like letting go of summer.

Part of me selfishly hopes the cottage doesn’t sell so my siblings and I can fill it with our own children years from now to teach them the importance of family and togetherness. But since my family has three college tuitions to pay, I realize selling the lake house is the best option.

It will be upsetting to let go of our summer retreat, but I hope a new, young family will receive the gifts we inherited from the home for so long. And if it does sell, at least I won’t ever have to touch goose poop again.

Tara Hunt is an associate editor of this magazine. Email her at thunt5@nd.edu.