“The Catholic writer, in so far as he has the mind of the Church, will feel life from the standpoint of the central Christian mystery; that it has, for all its horror, been found by God to be worth dying for.”

— Flannery O’Connor

I once went as a “visiting writer” to the class of a friend who teaches third grade. No flies on these kids. “What is your genre?” one piped up. Another inquired, “When do you know to stop revising?” Finally, a little girl in a green sweater raised her hand and shyly asked, “Do you ever just sit and look out the window?” I thought: Now you are a writer.

I did not exactly choose writing. Writing chose me: wrenched me from a career as a lawyer when I was over 40, split me, shook me, gripped me hard and has never let go. I’d been sitting and looking out the window since the age of 3. I was thrilled to discover this was actually part of my vocation.

That I came into the Catholic Church at almost the same time I began writing — the mid-1990s — is no accident. Neither is the fact that I needed to get sober first. In the preface to her novel Wise Blood, the novelist and short-story writer Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) observed:

“That belief in Christ is to some a matter of life and death has been a stumbling block for readers who would prefer to think it a matter of no great consequence. For them [protagonist] Hazel Motes’ integrity lies in his trying with such vigor to get rid of the ragged figure who moves from tree to tree in the back of his mind. For the author, Hazel’s integrity lies in his not being able to.”

Over the years, O’Connor has become my literary mentor. From the beginning, I knew my life was to be ordered to writing: physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually.

From the beginning, I knew that writing was a sacrament, a marriage, a crucible.

From the beginning, I knew the stakes were life and death.

I knew those things without being told but, more than anyone else, Flannery O’Connor corroborated them: in her collected letters, The Habit of Being; in her essays, stories and novels; in her tragicomic view of life.

Stricken as a promising young writer by lupus, the same disease that had killed her father, she returned to her mother’s dairy farm in Milledgeville, Georgia. Fiercely intelligent, by all accounts a lifelong celibate, and a “hillbilly Thomist” (her phrase) who, health permitting, attended daily Mass, she lived out her life among people who had little appreciation of her work and died at the age of 39.

“I’m a full-time believer in writing habits,” she observed. “You may be able to do without them if you have genius but most of us only have talent and this is simply something that has to be assisted all the time by physical and mental habits or it dries up and blows away. . . . Of course you have to make your habits in this conform to what you can do. I write only about two hours every day because that’s all the energy I have, but I don’t let anything interfere with those two hours, at the same time and the same place.”

Nothing can interfere with those hours of writing, and all the other hours, I’ve found over the years, must go toward supporting them. Every morning I spend an hour in prayer: pondering the Gospels, listening to the birds. I eat reasonably well, try to get enough sleep, and exercise: not so much in service to “health” but so my nervous system will be calm enough for me to write. I don’t want to waste time cleaning up chaos, so I pay my bills on time, get my oil changed and put away my clothes. Human conflict causes me pain, and because I have many wounds and character defects that tend to create conflict, I work with a spiritual director.

I also struggle, like most writers, with the need to support myself. I struggle with a book publishing world in which the publisher gets roughly 90 percent and the writer gets roughly 10. I have spent long years coming to terms with the parable of the talents. I have fought for what I’m worth, and I have also come to realize that the talent is God’s. My job is to put my work out to the world and let go.

I’m not capable of doing any of this by myself; thus, I avail myself of the Sacraments. “The truth does not change with our ability to stomach it,” O’Connor observed. I need Christ in my stomach, my groin, my heart. Before giving a talk, I go to Confession.

I don’t mistake myself for O’Connor, who was a genius, nor do I flatter myself that she would have thought much of my work or even liked me. The master need not like the servant. What counts is that the servant hears, and what I hear is this: “A serious writer would gladly swap 100 readers now for 10 readers in 10 years or one reader in 100 years.”

I have never suffered from writer’s block. I’ve suffered frequently from disappointment, a sense of failure, borderline despair that I’m no good: a shortcut-taker, a hack.

I show up every morning anyway.

Within reach of my desk are a Bible, a breviary, an icon of Christ. I need all the help I can get so the half-remembered quotes, reflections and scraps of conversation that float through my subconscious at any given moment might cohere that day into the beginning of a paragraph or an essay or a post.

My desk is an altar on which are sacrificed a social life, most companionship and all hope of a life ordered to myself alone. I don’t watch TV, not because I’m anti-TV but because I don’t have time. My “door” is open and many enter: people who want to share their joys and sorrows; people who want to kvetch; people who want me to read their stories and give them feedback (which I can’t).

On an ideal day I work for several hours, and even on an ideal day there are many interruptions. The interruptions drive me to distraction and also help preserve a sense of humor: No one who swears as much as I do has any business trying to sound too profound, clever or holy. Every late afternoon or early evening I take an hour-long walk, during which I observe the tops of trees, the shapes of leaves, people’s faces. I play the piano for 15 or 20 minutes. I try to say Evening Prayer and do a short examination of conscience. I listen to the birds again.

Within that framework, inspiration flows: perpetually, abundantly, in ever astonishing and ever new ways. Inspiration flows and then I do the packhorse work of writing, shaping, revising.

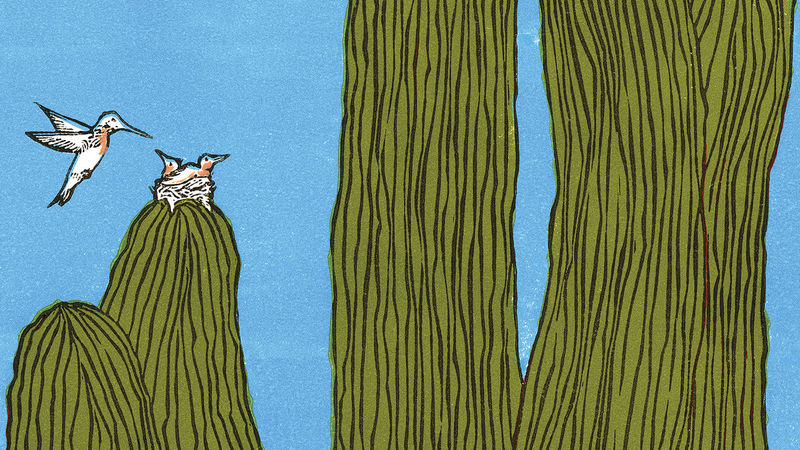

Packhorses need lots of solitude; at least, this one does. Recently, for example, I house-sat for a friend in relatively quiet Palm Springs. Outside the sliding glass doors to the pool was a cactus and way up on the cactus was a hummingbird nest with a mother hummingbird and, I eventually discerned, two tiny chicks. That hummingbird was the delight of my visit. I must have looked at that nest 500 times a day. I marveled, I took pictures.

One day a friend called from L.A. She’d just gotten her real estate license, and she was completely stressed out trying to run around making money. In the middle of her rant I reported, “There’s a hummingbird nest outside my window!” Silence. I could just hear her thinking, “Who cares about a stupid hummingbird nest: I have problems!” She couldn’t even hear me, God bless her. I mean, that little nest, the size of a pipe bowl, is more miraculous than any piece of real estate. So ask, seek, knock. Look out the window. The scales will fall from our eyes and that’s what we’ll find.

We’ll suffer, of course. No one wants to admit to suffering, to loneliness, and my strength as a writer, such as it is, may be that I’m not afraid to cop to my suffering. Single, aging, a mind that runs in obsessive ruts. Madly critical, especially of myself; violently impatient. Have not figured out how to have or to be in the perfect family, the perfect circle of friends, the perfect — or really any — relationship. Have never owned a house — have never even owned a washer-dryer! Seemingly incapable of writing a bestseller. And I sincerely believe I am possibly the luckiest person alive.

O’Connor suffered greatly, without self-pity or complaint. That she suffered, in and with Christ, was her genius. That is what makes her writing sublime.

And so one more morning I rise, pray, go to my desk. Always, in the back of my mind, is the ragged figure of Christ.

I pray to bear my own suffering.

I pray to be worthy to call myself a writer.

I pray for one reader, a hundred years from now.

Heather King is a Los-Angeles based writer, speaker and Catholic convert with three memoirs — Parched; Redeemed; and Shirt of Flame: A Year with St. Thérèse of Lisieux. She appears monthly in Magnificat and blogs at shirtofflame.blogspot.com. Her website is heather-king.com.