Act 1, Scene 1

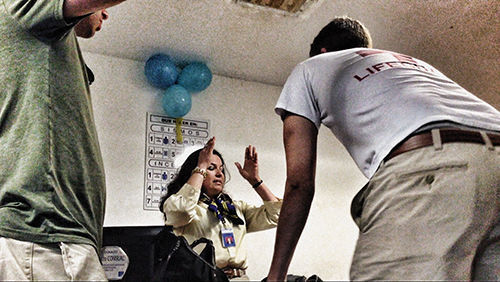

[Setting: Customs office in Managua, Nicaragua. After all of their photo and video equipment is detained, the What Would You Fight For crew members face off with an angry customs official who has determined that the process to retrieve their equipment will be as tangled as her blue and yellow scarf. The team has three days to shoot an ad that will air to millions of people nationwide and no equipment with which to film it.]

The walls were decked with a shrine to Che Guevara. As the What Would You Fight For crew members sat waiting for the customs official to return from her four-hour lunch break, they stared at the photos of the Marxist revolutionary. He stared back with a dark, steely gaze, forewarning the bureaucratic snarls to come.

In the summer of 2013, the team had flown into the Augusto C. Sandino International Airport in Managua, Nicaragua’s capital city, on assignment to shoot the ad, “Fighting to Build Bridges,” to air during the 2013 Notre Dame-USC game. The ad would focus on Notre Dame Students Empowering through Engineering Development (ND SEED), a group that has partnered with the nonprofit Bridges to Prosperity, which sends students to build bridges in rural, impoverished communities. The bridges provide better access to health care, education and markets, and permit easier travel during wet seasons.

But the bridge between Notre Dame and Nicaraguan customs had been neglected, leaving all but one camera on the other side of the bureaucratic wall. Though the team had been told it had fulfilled all the necessary procedures, the cranky customs official claimed otherwise. At first she alleged inadequate paperwork, then insufficient signatures, then typos on Nicaraguan documents that rendered them useless. Despite two days of negotiations, translations and pleading by Notre Dame senior Luis Llanos, the star of the two-minute spot and only Spanish speaker in the group, the customs lady would not budge. It was now Friday afternoon, offices were closing for the weekend, and the crew was to leave the country on Monday. They would have one basic camera with no extra lenses, lighting or audio equipment to shoot a professional-level ad that would air on national television.

“Our alternatives were to see what a Nicaragua jail looked like or to regroup,” says Mike Cloonan ’95J.D./MBA, line producer for the ads. “That’s when we decided to use the equipment we had and see what other resources existed on a Friday night in Managua because we only had that weekend to finish the shoot.”

To the Managua mall they went.

Act 3, Scene 1

The What Would You Fight For campaign began in 2007 when Notre Dame administrators approached NBC colleagues with the idea of producing commercial spots to highlight academic projects that would distinguish Notre Dame as a research institution. NBC agreed to grant two minutes of free premium air, the final moments of halftime, to Notre Dame during every home game. “We viewed it as a really collaborative effort to showcase some of the unique things happening at Notre Dame,” says Rob Hyland, NBC coordinating producer.

“The normal institutional ad is 30 seconds. Basically those are just a montage of scenes and a few words about how great your university is. But they don’t differentiate your university from another school because you only have 30 seconds,” Cloonan says. “By NBC giving Notre Dame two minutes, you can tell a story. You can capture people’s interest and attention, and they walk away knowing something more about what Notre Dame is doing to make a positive impact in the world.”

Two minutes of air time is an extraordinary opportunity, but it also means many more minutes of preparation, of travel, of filming. Ben Tishler, director of the campaign, says that for a typical two-minute ad, between 10 and 14 hours of film is shot. But the most difficult challenge isn’t breaking down that footage, he says. It isn’t the travel. It isn’t the preparation. The most challenging part, the crew agrees, is finding the right stories.

“There are a lot of neat things happening at Notre Dame, but that doesn’t mean there are a lot of things that translate well to a two-minute television feature,” says former producer Betsy Lazzeri Riley ’03.

Every January the team members sit down with their colleagues at Notre Dame to sift through a list of around 30 ideas that have been pitched by administrators, alumni and students. From there, they choose a dozen or so projects to investigate.

Because each ad slot is worth approximately $250,000 of airtime, each proposal must meet rigorous criteria, says Beth Lohmuller Grisoli ’87, ’90M.A., director of Multimedia Services at Notre Dame. “We’re particularly interested in research that has already had an impact or is having an impact,” she says. “When you’re seeing something go from a lab out into a community and making a difference . . . that’s exciting.”

That impact must be easily visualized and showcased, Grisoli points out. It must transform lives. It must solve a timely or timeless problem. If the topic can tie into one of the games, say, military research during the Notre Dame-Navy game, even better. It should also tap into the distinctive Catholic mission of Notre Dame, she says. Once it fits those conditions, along with a lengthy list of others, it has to be unlike any other ad slated to air that season. Cumulatively, the segments should show the full breadth of the University’s work. And, most important for NBC, the subject must be appealing to a football audience.

“I always challenge the school to remember one thing: These spots play within the context of a college football game on network television,” Hyland says, “so if they’re strictly research oriented, with no human connection, if it’s a bunch of test tubes and lab shots, no one is going to be grabbed. . . . You need to capture the attention of the football audience within the first 15 seconds of that two-minute spot or people are not going to pay attention at all.”

Over the years, team members have discovered that the best research does not always lead to the best ad. They need scholarly research, certainly, but they also need a compelling backstory, tangible results and relatability. They need to be able to quickly explain not only the complex academic research, like medications to treat lymphatic filariasis or how robots can help autistic children, but also how the solutions can change people’s lives.

“We try to work closely with [professors] to help translate the work that they do into a more digestible form,” says Tishler. “Ahead of time we try to do some interviewing to first understand their work, and then put it in as much laymen’s terms as possible.”

Act 1, Scene 2

[Shopping center, Managua, Nicaragua. Put aside any preconceptions of a Third World country’s mall. Luxury cars line the parking lot, and designer stores fill the two-story building. The crew is on a hunt for specialty cameras and equipment.]

“We went to the nicest shopping mall in Managua to see if the camera store there had any equipment we could buy to supplement the one nice camera our cameraman had wisely kept in his carry-on bag,” Cloonan recounts. “The camera store didn’t have anything that was suitable, but there was a high-end fashion show going on. On the media-photo deck, we saw this gentleman who had the same type of camera as our cameraman, which is a very high-end Nikon camera. We approached him and asked him if there was anywhere to buy equipment like that, and he said no. . . . He had bought his camera and all his equipment off of Amazon.com.”

With no hope of purchasing supplementary camera equipment, the crew thought of an alternate solution: How about hiring the Nicaraguan camera guy? For $200 a day, Dennis, their new Nicaraguan colleague, agreed to join them in a rural town to shoot the Notre Dame students building bridges and to provide all of his lenses, tripods and filters for their use, Cloonan says. The shoot still lacked microphones and booms, but a crew member had previously mailed a small, digital recorder for pre-interviews. With some duct tape and a pole, the crew captured sound bites during the interviews.

“We didn’t have the equipment we usually rely on, like dollies and boom mics,” says Cloonan, “so we had to be creative in how we shot the piece, and I think it was one of the best ads we’ve ever done.”

Happy with the content they gathered, crew members prepared to return home. But they had one more surprise waiting at the airport.

“Not only did we not get any of our gear, they also kindly charged us a storage fee for the privilege of not getting our gear,” Cloonan jokes.

They paid the bill and took their unused gear back to the United States.

Act 2, Scene 1

Nicaragua wasn’t the first time the What Would You Fight For team had experienced snags in its worldwide travels.

In Nepal, while covering the importance of women’s education, they hiked in the rain with all of their gear through rolling foothills of rice paddies, only to discover their feet and ankles were covered in leeches. They also awoke the next morning to discover they had been sleeping next to a herd of water buffalo.

In Paraguay, on assignment to tape footage of the gravesite of a child soldier, the car got stuck in the mud and the crew members had to hire a tractor to bring them the rest of the way.

“There are always moments in every shoot where things don’t go quite right, but when you’re traveling internationally, you’re just adding more variables,” Riley says. “When you’re traveling further away from the First World and cultures you’re more familiar with, the variables tend to increase.”

But for all the distance, all the trials, Riley, Tishler and Cloonan resoundingly agree they’ve never felt unsafe. NBC and Notre Dame have prohibited shoots in dangerous locations, like Egypt during Arab spring and Iraq during the War on Terror. For those ads, they’ve improvised — re-created scenes in American deserts, relied on stock footage and hired local cameramen to capture riots.

When the crew does land in a precarious location, it relies heavily on the professors who have done research in the places it visits. The professors provide information about cultural customs, like what is most appropriate for the crew to wear, safe places to stay and how to travel from place to place, Riley says. In remote locations, the partnership with NBC becomes indispensable, too. NBC is able to use its vast international network to book trusted fixers — locals who help translate, scout locations and assist with casting — as well as security personnel. The network also provides a skilled production management team that vets locations and personnel ahead of time and can step in to find solutions when misfortunes arise.

Act 2, Scene 2

[Setting: Eldoret, Kenya. The team has wrapped up shooting “Fighting to Protect the Sick,” an ad that features research by Professor Marya Liberman on inexpensive and efficient tests for counterfeit medications, which kill 300,000 people annually. On its last morning, the What Would You Fight For crew awakes bleary-eyed to the news that the Nairobi airport, where the team is to fly out later that day, is on fire.]

“The fire had been going on for hours,” Cloonan recounts. “There weren’t enough fire trucks, enough water. The first responders were looting as opposed to putting out the fire. It quickly became apparent that the international part of the airport was not going to open very quickly, so we needed to look at alternatives.”

The best bet to nab an international flight was the Entebbe International Airport just outside Kampala, Uganda. It’s nearly the same distance as the Nairobi airport but would require a border crossing that could prove impossible with expensive, American gear.

“That’s one of the really nice things of having a large company with global experience, like NBC Sports, behind you,” says Cloonan. “When you do run into a situation or a crisis internationally, they have the experience and resources to bail you out.” NBC often reports in Kenya before summer Olympic games because of the concentration of track and field athletes, so it has built an extensive network there.

At 8 a.m. local time, 1 a.m. in New York, Cloonan called the production manager who works for both What Would You Fight For and the Olympics. Using her contacts and knowledge of the area, she immediately began arrangements for a private flight that would allow the crew to transport its equipment across the border without hitting an additional customs checkpoint. Through the night, NBC personnel analyzed pilot logs, verified insurance records and determined the exact space and weight requirements for the luggage, ensuring a safe flight for the crew, student and professor. Within eight hours, all flights were rebooked out of the Entebbe airport, and a private plane would be sent the following morning to retrieve them from Eldoret, allowing them to skip the process of a border checkpoint.

Act 2, Scene 3

[Setting: Manhattan, New York. The What Would You Fight For editing studio is on the 10th floor of a building on 36th street near Broadway. There, the rough edit of “Fighting to Stop Tuberculosis” sits in pieces on hard drives waiting to be compiled before Saturday’s game. But Hurricane Sandy hits, knocking out power to that building and all buildings within a half-dozen blocks in any direction. Saturday’s game draws near, and the building and the video remain inaccessible.]

Any other weekend, the ad could have been bumped to the next home game. But the final home game of the 2012 season was set to run “Fighting to Develop Great Leaders,” a segment about Caitlin Crommett, a Hesburgh-Yusko scholar who started a nonprofit organization to grant the last wishes of hospice patients. If the tuberculosis ad were delayed, Crommett’s would get bumped to the next season and the featured hospice patients would likely die before it aired.

With just one day left to finish the ad, Peter Iannuccilli, editor of the spot, finally convinced the landlord to open the powerless building so he could retrieve the tuberculosis footage. Once inside, they knocked down a stairwell door, climbed 10 flights of dark stairs and then carried a computer, tapes and additional hard drives back down to a cab that would take them 15 blocks to NBC’s headquarters at 30 Rockefeller Plaza.

The trouble didn’t end there. The What Would You Fight For ads run on an entirely different system than the rest of NBC, Cloonan explains, so editors had to reinstall all their software before they could reassemble the ad.

“Even as of lunchtime [on Friday] we couldn’t say which ad would air the next day,” he says.

“Fighting to Stop Tuberculosis” aired, as planned.

Act 3, Scene 2

“What Would You Fight For” has just wrapped up its seventh season. Forty-six ads later, it is growing in popularity and recognition, and the number of story suggestions keeps increasing.

“Every year when we’re finished, we re-evaluate the campaign. At this point our philosophy is as long as there are great stories to tell, this campaign can continue,” Grisoli says.

So far it has covered treatments of concussions, cancer and Niemann-Pick Type C. It has discussed Catholic education and sustainable energy, war and peace, national security and social responsibility. It has recruited students, scholars and raised funds. And it’s given time and recognition to work that may have otherwise remained anonymous.

What’s next? Perhaps new places — China and India have yet to be covered. Perhaps new storytelling efforts. Or perhaps alumni stories in addition to the faculty and student ones, Cloonan says. Whatever the future, crew members are genuinely grateful for the opportunities they’ve had to tell great stories. And, Cloonan adds, for the frequent flyer miles.

Tara Hunt is an associate editor of this magazine.