First-year student Sara Abdel-Rahim is a long way from her conservative Muslim family’s home in Florida, and an even longer way from the family’s homeland in Egypt. When she chose to come to Notre Dame, Abdel-Rahim didn’t even know it was a Catholic school. Spring visitation convinced her that this was her collegiate home — “There’s something in the bricks,” she says with a smile, showing that she knows her ND history.

In her culture, children generally stay geographically close to the family, but Abdel-Rahim doesn’t regret leaving sunny Florida for snow-covered South Bend. She likes Notre Dame’s “faithful” culture — even if that faith isn’t her own. She goes to Mass at least once a week, out of respect for the ND community and for her dorm, Farley, where she is dismantling stereotypes.

The one thing you wouldn’t think when you see Abdel-Rahim is “rapper.” And this girl can rap. She wins talent shows, writes her own rhymes and likes Lil Wayne and Drake. She brought down the house at the 2013 Black Images talent show at Notre Dame.

Abdel-Rahim, who wants to practice international law, hopes her presence will teach others about her faith and culture. She calls herself one of the faces of Islam at Notre Dame, which comes with its own set of difficulties but is something she takes in stride. Sometimes other students or professors confuse her for one of the few other veiled girls (all of whom are international students) at Notre Dame, talking to her about classes she’s not in or events she didn’t attend. Sometimes she corrects people; other times, she plays along. It’s part of the territory, she says, but hopes people will grow to know her beyond her hijab, beyond this overt expression of her faith.

Many of her raps are about her life as a young adult, as a woman, as a Muslim. Sometimes they’re about all three. But her rap performances all end with a signature line: “My name is Sara and you will see, there ain’t no veiled girl better than me.”

— Amanda Gray ’12, reporter for the South Bend Tribune.

When Katie Beirne Fallon ’98 moved into Pasquerilla East Hall in autumn 1994, she had her future mapped out: After studying government and international relations at Notre Dame, she would move back to her native Cleveland and run for public office.

“I got involved in student government the first week I was there, and I was freshman class president,” Fallon says. “Over time, as you can imagine, I developed other priorities at school.” Those included interhall football — she broke a finger during one championship game in Notre Dame Stadium — and studying hard enough to earn prestigious Truman and Marshall scholarships.

Fallon never did move back to Cleveland to mount a campaign. Instead, she carved a path to the epicenter of the political world: Last December, President Obama named Fallon his new director of legislative affairs, the White House’s top liaison to Congress.

It’s a critical post in the dysfunctional world of modern-day Washington. The Obama administration frequently is criticized for failing to engage legislative leaders from both parties. Meanwhile, partisan bickering has crippled Congress, leading to a 16-day government shutdown last fall.

Fallon brings a wealth of Capitol Hill experience to the job. She spent eight years working as a top aide to Senator Chuck Schumer of New York. While the White House benefits from her close ties with Senate Democrats, Fallon also focuses a lot of her energy on trying to repair relationships with congressional Republicans.

“As a Democrat in a Republican family I have had to learn over time how to put politics aside for a greater cause,” says Fallon, the second oldest of eight children. “That’s certainly been valuable for me in this town.”

That diplomatic approach is part of what makes Fallon, according to aides from both sides of the aisle, one of the most effective behind-the-scenes operatives in Washington. Just don’t expect her to step into the limelight anytime soon.

Asked if she still considers moving back to Cleveland to resuscitate the political career she left behind at Notre Dame, Fallon laughs and offers a one-word response: “No.”

— Kevin Brennan ’07, senior alumni editor of this magazine.

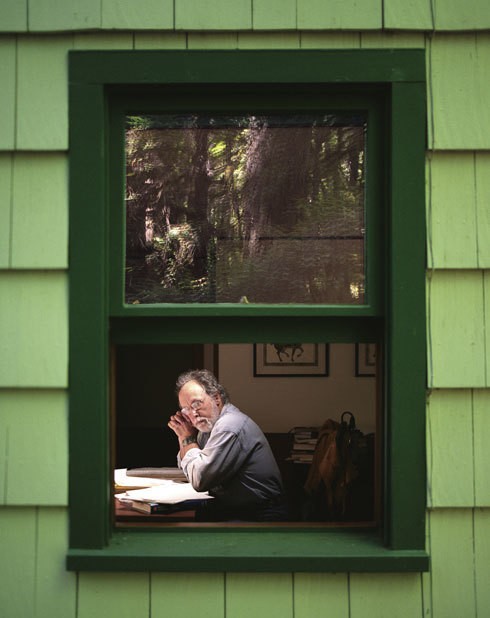

Here are some things to know about Barry Lopez ’66, ’68M.A. He had the childhood from hell and somehow survived it and built a gracious, gentle, generous self who has no kidding thousands of friends around the world, in every conceivable walk of life. He has traveled to perhaps a hundred countries in the course of his work as writer and naturalist and agent of reverence. He has traveled thoroughly in the hottest and coldest and wettest and driest and most dangerous places on earth. He is the author of more than 20 books large and small. He has lived in the same woods on a river in Oregon for more than 40 years. He is the most riveting speaker you ever heard, without any of the theatrical masks that famous speakers often use. He once told me quite seriously that his ambition was to overthrow the Enlightenment — not back toward chaos but forward toward genuine respect for the many other doors of perception and wisdom than mere reason.

He is a serious student of aboriginal culture, especially in his native North America. He was going to major in aerospace engineering at Notre Dame but became entranced by storytelling and wilderness and has never stopped being entranced by the way that stories are powerful and holy and deft levers for opening heads and hearts. He became one of the great storytellers of our time by traveling and listening and reading ferociously and leaving his ego at home. No one I have read or heard in my 40 years as a voting American citizen has been as intent and eloquent about communal responsibility, about the astounding possibility of Americanness still, about capitalism’s predilection toward savagery to the helpless and broken among us, about human beings’ epic, careless, breathtakingly arrogant destruction of other species also breathed into life by the Creator.

He is justly famous for his sinewy writing, but he should be famous for his insistence on reverence bigger and wilder than any religion can claim. He once wrote an essay about stopping to move smashed animals from the road out of respect for who they might have been in their cultures. No one I know has written more searingly not only of the savagery he suffered as a child but of the horrifying prevalence of rape in our culture and our horrifying refusal to do something about it; instead we sprint after the next new gleaming toy, and drool over the shiny new half-naked celebrity of the moment, and cover our ears to the screams of women and children.

If ever there was a case where what a man’s life and work meant was far bigger than his glittering resume, Barry is that man. Yes, he won the National Book Award for Arctic Dreams. Yes, he is the finest writer in the long history of the University of Notre Dame. Yes, he will be read in America and abroad for centuries to come. But I think he is a great man not for his masterful craft and surpassing eloquence; he is a great man because he will not concede that his country and his species are capable only of fitful grace and mercy and wisdom. He is a great man because of his unquenchable, unblinking hope, despite all the evidence against. No one I know has been such a relentless, imaginative, unswerving agent for reverence and attentiveness and moral responsibility. When I have dark days, I remember that Barry is at work, in a room in the woods by a crystal river, and hope rises up again in me like a fist clenched against the dark.

— Brian Doyle is editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland.

When Marianne Cusato ’97 decided it was time to leave Manhattan, despite how much she loved it, she looked around and chose to settle in Miami, Florida. “It’s all about finding that sweet spot,” she says, which includes thinking about the lifestyle associated with one’s residential area.

“Miami is an urban city; it’s easy to meet people,” the architect adds. “I was looking for a calmer lifestyle. . . . I love to walk.”

Small is big with her. And so is a water view. That’s why she lives in a one-bedroom apartment in a high-rise overlooking the ocean. The choice was a result of deciding what was most important to her.

Cusato is known for her award-winning design of the Katrina Cottage, a 300-square-foot hurricane-proof house suggested as alternative emergency housing in Mississippi for those displaced by the 2005 storm.

In her design work, Cusato says she always applies the principles she learned during her first architecture class at Notre Dame: firmness, commodity and beauty. When her team was working on designs to replace the FEMA trailers used after the hurricane, it translated those architectural precepts of Roman architect Vitruvius as “function, cost and delight.”

Functional and affordable were necessary, of course, “but if you don’t love it,” she says, “it’s not going to work.”

Which is why her team made a point of adding the delight to the Katrina Cottages, and probably why those small modular homesteads with their cute front porches and pastel faces earned numerous architectural awards, and why the cottages and their variations are now popping up throughout the country.

That doesn’t mean Cusato thinks her best work is behind her. She turns 40 this year, a milestone she views with optimism. “People practicing architecture don’t actually get good until they’re 40,” she says. “For me, professionally, I’m kind of hitting my stride.”

— Carol Schaal is managing editor of this magazine.

The first sea story Father Bill Dorwart, CSC, ’76, ’80M.Div. tells is so dark you feel hope leaching out of your chest.

He’s sitting alone in his chaplain’s office, late on a placid June evening in 1990. The aircraft carrier USS Midway, tied to a pier in a Japanese port, is a ghost town, its 5,000 residents seeking solace in phone calls home and other distractions. But the noise and images of the day are seared into Dorwart’s mind as he toils over arrangements for a memorial service.

The medical emergency alarm that pulled him from lunch. The chaos of the fire zone. The screaming boys and their blackened skin; the “silent, shocked men whose faces were white with horror.” The two “charred, unrecognizable figures” they found belowdecks at the explosion site, locked together in one final, human embrace.

As the priest continues preparing for the memorial, a knock comes at the door — a distraught sailor whose call home was answered by the local sheriff. Sitting practically knee to knee with the serviceman, Dorwart places a second call to the boy’s home. The sheriff answers again and explains that he has news he didn’t want to share with a young man alone. His parents have been murdered. His brother is a suspect.

The priest’s instinct is to get out of there, fast.

“Then you think, what does a chaplain represent? Nobody would know what to say. But you know you’re there, partly because God planted you there and because God himself is there for this person.”

Navy chaplains were there for Dorwart when he was a young aviation technician. They helped him find his vocation. A chaplain, he says, is a kind of steady hope, a consolation, a restorer of trust. The gentle, reserved Dorwart has been that for thousands of men and women in the U.S. Navy over two separate stints spanning 13 years since his 1980 ordination as a Holy Cross priest. “The chaplain becomes one of the few things in the machinery that says, ‘I’m here for you,’” explains the 64-year-old priest who served in Operation Desert Storm and returned to military ministry in 2008.

These days Dorwart, who plays guitar and composes psalms and hymns, is assigned to a Washington Navy Yard still anguished after the September 2013 shooting that killed 13 civilian workers and wounded eight others. He performs as many as six funerals or memorials at Arlington National Cemetery each day. But true to his Holy Cross identity, Dorwart’s hope is undimmed and he wants to go back out to sea. “It’s an adventure,” he says. “Sometimes it feels like work, but most often it’s a delight. I’d have to say that about the whole journey.”

— John Nagy ’00M.A., an associate editor of this magazine.

Jimmy Dunne ’78 is all about relationships. Whether counseling the families of Sandler O’Neill colleagues killed during the attacks of 9/11 or advising the financial executives from major banks around the world or negotiating the golf course, Dunne is a connector of people. He loves being with people, cares about people. He’s also a very competitive man. He needs golf to regulate his competitive drive and the sounds of the ocean on Long Island or Palm Beach to nurture and calm his soul.

He is also an incredibly generous man whose life has been largely defined by his response to tragedy. Dunne did not go into Sandler O’Neill’s World Trade Center office — the 104th floor of Tower Two — on the morning of September 11, 2001. Eighty-three Sandler O’Neill employees did. Sixty-six were killed, including the two close friends with whom he had launched the investment firm. Dunne comforted the distraught survivors, spoke at funerals and set up a grieving center at a New York City hotel to take care of the families. He paid the victims’ full salaries (plus bonuses) to their families through the end of the year and also provided them health insurance for five years (more years were later added). A foundation was established to pay educational expenses of the children of the deceased.

Dunne also rebuilt Sandler O’Neill, even though it had lost nearly 40 percent of its national work force, countless contacts and most of its financial records. The firm is today stronger, larger, more profitable than ever.

The University trustee is someone you can sit with in workout shorts and watch the Notre Dame-Duke basketball game or join as a spectator at the Masters at Augusta. He treats everyone the same, from the caddie room attendants to the head pro. Dunne is a talented and astute businessman, one of the great leaders of Wall Street. He is generous in spirit, a man of the people who cares about the world we live in and how we can make it better for the future.

— Scott Malpass ’84, ’86MBA, is Notre Dame’s vice president and chief investment officer.

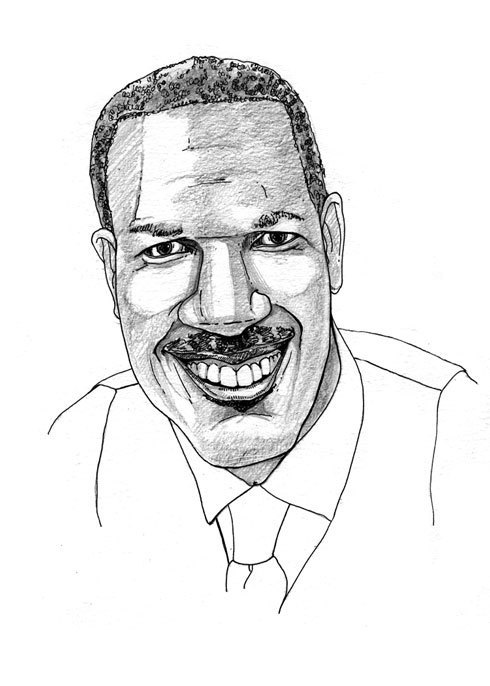

When Darrell Gordon ’88, ’89MSA interviewed to be the Wernle Youth & Family Treatment Center’s president and CEO, he drew a crowd.

“All the kids just started following me,” Gordon says, recalling the first impression he made on the residents, to say nothing of the staff and board members. A dozen years later, he’s still their leader.

The nonprofit agency recruited Gordon from the NCAA, where he developed “Stay in Bounds,” a youth character education program. The former Notre Dame linebacker, who had previously worked in sports management and at Advanced Drainage Systems for the late Frank Eck ’44, had grand ambitions.

“We revamped our leadership team and our directors. We re-evaluated our development prospect team. We rebranded our image and our logos. We went about fundraising differently than we had in the past, reached more people,” Gordon says. “And we re-evaluated our campus and found a way to better facilitate the needs of our kids.”

Those needs are immense. On its 72-acre campus in Richmond, Indiana, Wernle houses 79 males, ages 6 to 21, suffering from the tragic effects of abuse and neglect — social and educational problems, substance abuse, mental illness. A staff of 120 provides treatment with the goal of reuniting the residents with their families.

For Gordon, the job combines his professional aspirations “to transform an organization and transform a group of young individuals to live a better life.” In the throes of a $10 million fundraising campaign, he’s focused on the organizational level, but he makes time for the individual, too.

Students who earn straight As have lunch with the CEO as a reward. He always asks for their feedback. One resident responded with three pages of suggestions and one request: that Gordon present those ideas to the staff. “That gave him more joy,” he says, “than anything he had done on our campus.”

Gordon believes children develop emotional scaffolding to navigate life outside Wernle’s supportive structure from intensive treatment combined with those small moments when their contributions are recognized and put toward a greater good.

“We’re a strength-based organization,” he says — and one of its greatest is Gordon himself.

— Jason Kelly ’95, a former sports columnist for the South Bend Tribune, is an associate editor of the University of Chicago Magazine.

As one of 12 black freshmen at Notre Dame in 1965, Dr. Bill Hurd ’69 was a pioneer.

His life is one of giant steps like this. A five-time All-American sprinter — he still holds two Notre Dame records and nearly qualified for the 1968 Olympic team — Hurd was also an honors electrical engineering student and a standout jazz saxophonist who was named “most promising sax” at the Collegiate Jazz Festival.

In Hurd’s senior year, Ara Parseghian personally invited him to join the football team for a season (he played wideout). Father Ted Hesburgh, CSC, encouraged him apply for a Rhodes Scholarship (he was a finalist).

Now a practicing ophthalmologist with two U.S./foreign patents for ocular devices, the Memphis native annually travels to such places as Madagascar, Mexico and Kenya, where he performs pro bono eye surgeries for hundreds.

“Most of these people [have] never seen a doctor before, let alone an eye surgeon,” says Hurd, who is composing an autobiography tentatively titled Memphis to Madagascar.

Even with a career as remarkable as his — “I’ve been very blessed,” he says — Hurd is reticent to single out a defining moment. There is his latest album, Return of the Hip, which opened in 2014 near the top of the Memphis jazz charts. There is the NCAA Silver Anniversary Award he received in 1994 alongside Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and other legends. There is the pride, shared with his wife, Rhynette, of seeing their sons Bill Jr. and Ryan ’05 attend Notre Dame.

If there is a defining moment, it might be this: During one of his medical journeys to Madagascar, Hurd successfully restored vision to an elderly woman who “had never seen her grandchild before.” The surgery complete, Hurd removed her eye patch. As she saw her family for the first time, “She just started crying. And I did too.”

— Michael Rodio ’12 writes professionally.

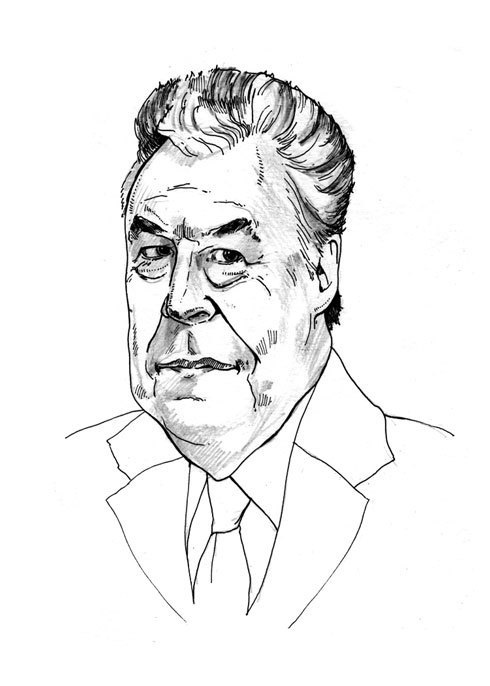

U.S. Representative Peter King ’68J.D., in his 11th term representing New York’s Long Island, is one of Capitol Hill’s most gregarious Republicans and an unapologetic moderate. He is also thinking about launching a long-shot presidential campaign. “Oh, I’ll be making a few trips to New Hampshire this year,” he says with a wink during an interview near the House floor. “I’m really concerned about where my party is heading, with Ted Cruz shutting down the government and Rand Paul going after the National Security Agency.”

King, 70, a regular on the Sunday talk shows, acknowledges that such a bid would be difficult, especially for an outspoken critic of Tea Party conservatives with a small national fundraising base. But he plans to explore the idea for the rest of the year, huddling with activists and talking up his views. On foreign policy, the former Homeland Security Committee chairman is a hawk and an ardent supporter of federal anti-terror efforts. On domestic policy, he is pro-labor and populist.

“We seem to always be pushing people away from the GOP instead of toward us, and that’s a shame,” King says. “We’ve got this group in the party that’s in an echo chamber. But we’ve got to get back to winning the blue-collar voters and former Reagan Democrats.”

In December, King founded a political-action committee to promote his brand of Republicanism. Trips to other early primary states are in the works. Last year, King, who gained national prominence in the 1990s for his support of President Bill Clinton during impeachment proceedings, drew notice again for opposing the shutdown, sponsoring gun-control legislation and fiercely battling conservatives who were opposed to giving billions in relief to victims of Hurricane Sandy.

King chuckles when asked whether he could compete with more prominent Republican hopefuls such as New Jersey Governor Chris Christie. “Come on, it’s early,” he says. “I don’t have a staff right now, no consultants — nothing. Just making these trips on my own. But I’ll tell you, it is fun, and after some long weeks here, it’s sure nice to get out there.”

— Robert Costa ’08, a columnist for The Washington Post.

Matt Knott ’92 says his four children, who range in age from 8 to 14, seemed to understand what his job as president of Feeding America entailed. Then they joined their father and their mother, Agnes Taylor Knott ’93, as volunteers at a local soup kitchen.

“I think that was a real eye-opening experience for them,” he says.

When Knott started at Feeding America in 2008, he had his own eye-opening experience. “The magnitude of the issue was a surprise to me,” he says. “Gosh, the nearly one in six who are struggling to feed their families, I never knew. . . .”

He knows now.

The Chicago-based Feeding America has a dual mission. The first is to feed the hungry through a nationwide network of member food banks. And that “hungry” is a rather shocking number: 49 million Americans are classified as “food insecure.”

The second is to lead the fight to end hunger, a complex mission that includes such things as securing food which would otherwise go to waste, advancing public policy solutions, and partnering with other organizations to create a collective impact that addresses the root causes of hunger.

During Knott’s visits to food banks across the United States, he says clients occasionally will share their stories of struggle, stories of mothers who skip meals so their children can eat or fathers who lose sleep because they are afraid they will never make enough money to keep the cupboards filled.

“It touches me emotionally,” he says. “It just strikes me as unfair that people should have to deal with issues of basic necessities in such devastating ways.”

At the same time, he says, “I’ve been really inspired by the people who are leading and working in food banks around the country,” people who must deal with the business side of their nonprofit, speak to the community and “also be very good at building a capable organization with limited resources.”

While Knott and his children were surprised at what they learned about the prevalence of hunger in America, he is also aware that “for people who are learning about this for the first time, it can seem difficult to understand how to make a difference.”

While Feeding America’s member food banks “provide the equivalent of about 3.2 billion meals annually to 37 million Americans,” Knott wants people to know that making small contributions or volunteering for an afternoon shift at a food bank can add up. “If everyone tries a little bit to help their neighbor, we’ll make a huge difference together.”

— Carol Schaal ’91M.A., managing editor of this magazine.

Corporate CEOs don’t often make the news for defying the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and championing sustainability over short-term profits. But that’s what happened when Mike McNally ’77, president and CEO of Skanska USA, one of the nation’s foremost construction firms, called out lobbyists’ efforts to weaken green building standards.

McNally, writing in The Washington Post last June, accused members of “the chemical industry and its cronies” of “putting their bottom lines first and social responsibility second” for advancing legislation that would effectively ban the future use of the LEED green rating system in federal buildings.

When McNally learned that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce supported the chemical companies, he asked the chamber to change course. When it didn’t, the Skanska CEO publicly withdrew his firm’s membership, creating industry buzz yet earning accolades from the U.S. Green Building Council. “Mike McNally was the one person in the entire world,” said the council’s president and CEO Rick Fedrizzi, “who stood up and said enough is enough.”

While reaffirming the need for construction firms to earn profits and serve both customers and shareholders, McNally’s Washington Post op-ed also noted: “Long-term success requires a longer view.” At Skanska, McNally said, sustainability is a core value and “the intersection of that responsibility and profitability is in green buildings.”

McNally, who began his career as an offshore engineer in Egypt, heads up U.S. operations for the global firm headquartered in Stockholm. With 8,300 U.S. employees in 39 offices across the country, Skanska USA generates about $6 billion in revenues annually, managing large-scale construction, infrastructure and commercial development projects in healthcare, education, government, sports and transportation. The firm recently completed the world’s fourth “Living Building,” Seattle’s Bertschi School Science Classroom, created entirely of healthy building materials and using zero net energy and zero net water.

“Sometimes you’ve got to act,” the Rhode Island resident says, explaining the stand he took. “It’s all about sticking to your values. The status quo is not good for the planet. What we’re trying to do at Skanska is to create a platform where our employees can make the world a better place.”

— Kerry Temple ’74, editor of this magazine.

Alex Montoya ’96 has been in two Steven Spielberg movies. Being on the set with Tom Cruise made him realize, he says, how much he and the actor look alike — from the neck down. He carried the Olympic torch in 1996 for the summer games in Atlanta, has written two books, earned a master’s in sports management and fulfilled a dream when he went to work for the San Diego Padres in 2006. He is the team’s manager of Latino affairs.

In 2000 one San Diego magazine dubbed him one of 50 San Diegans to watch, and in 2013 another tabbed him one of “40 under 40” San Diegans to celebrate. In 2012 he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from San Diego’s Hispanic Chamber of Commerce — at age 38.

Accepted into Notre Dame, he was set to be deported to his native Colombia before he could enroll, even though he had lived with his aunt and uncle in California since age 4. The irrepressibly, contagiously cheerful Montoya convinced a judge to rescind the order. In his four years at Notre Dame he was instrumental in changing the school’s approach to serving special needs students . . . because the most remarkable thing — maybe — about Alejandro Montoya is that he was born with one leg and no arms.

The doctors never knew why. Montoya, who shaves with his foot, chose to live an extraordinary life anyway. He gamely straps on prosthetic arms and hooks, which he operates with subtle shoulder movements, and makes the world a better place for everyone he meets.

“From St. Ed’s Hall to the Joyce Center, he seemed to know everyone as we’d walk across campus,” says Bob Mundy ’76, ’81M.A., the admissions counselor who became a close friend. “He had a way of making people around him happy. Despite his dramatic physical challenges, he just wanted to be, and was, another college kid — playing soccer on the quad, going to the weekend SYR or skipping the occasional class. He became a regular at our family dinner table and brought perspective and joy to our lives.”

Born in Medellin in 1974, Montoya faced a potentially grim future in Latin America. Acts of love transformed his life — the parents who let him go, and the aunt and uncle who took him into their San Diego home and raised him as their own.

— Kerry Temple ’74, editor of this magazine.

For Mary Ellen O’Connell, drone use is not just a legal issue, not just a moral issue, it’s a Catholic issue.

If national security comes “at the expense of what we as Catholics believe to be the greatest human value — and that is human life — we have become an immoral and corrupt society,” says the Robert and Marion Short Chair in Law and a professor of international dispute resolution at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.

Since the first drone attack in 2002, O’Connell says the United States has killed as many as 4,100 people, including hundreds of children, in nonconflict zones in Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan. The CIA-run program, which uses anti-tank Hellfire missiles meant for combat, defies international law, she says, and, in conjunction with NSA surveillance, has led even U.S. allies to grow wary.

O’Connell came of age amid the colliding influences of Pope John XXIII’s encyclical “Peace on Earth,” the divisive Vietnam War and Vatican II: “From that background, I knew I wanted to fulfill my vocation as a Catholic through working for peace,” she says. En route to her law degree, she studied under Oscar Schachter, one of the first lawyers of the United Nations and namesake of one of O’Connell’s English bulldogs. (Her other pup, Auggie, is named after Saint Augustine.)

She practiced international law before turning to academia, although the Department of Defense called her away for a three-year stint as a military educator in Germany. There she met her husband, Peter Bauer, a U.S. Army interrogator. “I thought it was my time to do my own service for my country. It was after the Cold War; it seemed like the time international law would be very much a part of the U.S.’s international policy,” she says.

O’Connell and her husband have since settled in South Bend, where she has become a prominent voice on the legality and ethics of drone use. She has testified before Congress, given the Hersch Lauterpacht Memorial Lecture at her alma mater, the University of Cambridge, and has contributed to The New York Times, CNN and NPR. She will soon begin a one-year fellowship underwritten by the Templeton Foundation at Princeton, studying law and religious freedom at that university’s Center for Theological Inquiry and its Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

“Since religious conflict is at the heart of so many armed conflicts,” she says, “this is a great topic for me to be thinking about.”

— Tara Hunt ’12, an associate editor of this magazine.

“You never know what kind of greatness can come out of an American garage,” intones a recent Cadillac ad that offers the Wright brothers, Amazon and The Ramones as examples.

Someone on the creative team missed InterVol.

Greatness began flying out of Dr. Ralph Pennino’s garage near Rochester, New York, 25 years ago in the form of castoff medical supplies and equipment. Pennino ’75 had returned from a medical mission to Siberia convinced that much of what U.S. hospitals were throwing away daily at a substantial cost could be saving lives overseas, or even closer to home.

The plastic surgeon and hand specialist arranged to have box after jumbled box of surgical instruments, gauze and even complex items like EKG and anesthesia machines delivered from area hospitals to his home instead. He rounded up colleagues and friends to sort, catalogue and ship the materials.

Today InterVol’s core program is endorsed by the American Medical Association. A rotation of some 500 volunteers redirects several tons of would-be medical waste each week via local warehouses to “shoppers” all over the world willing to pay a nominal per-pound fee and shipping costs. The goods find their way into hospitals, clinics, zoos and even biology and art classrooms.

But the jazz-loving, wine-collecting chief of surgery of the Rochester General Health System wasn’t finished. “If you stop, you get bored,” Pennino says.

With InterVol’s co-founder Dr. Timothy O’Connor, Pennino launched another program that sends Rochester-area doctors and nurses on medical trips to such places as Belize and Haiti. Organizing locally, rather than through big NGOs, means sharing the experience with colleagues from home and building a network that has mobilized collegiate, corporate, media and nonprofit partners along with Rochester’s world-renowned medical community.

“My strength is facilitating people who want to give back,” he says. When the 2010 earthquake flattened the Haitian city of Léogâne, he put InterVol’s resources into play, attracting other first-responders among the Notre Dame alumni. Constellation Brands, a big supporter, offered jets to fly the doctors in and out of the Dominican Republic. Pennino had three cell phones active at once, making arrangements to cover the rest of the way.

While many NGOs have pulled out of Léogâne InterVol remains. Pennino himself has returned 12 times to perform surgeries alongside other alumni doctors. He continues working through InterVol and its partners to reboot the city’s hospital, bolster a new primary care clinic and even rebuild an orphanage. “I’m not a builder,” the born connector of needs and people says. “How’d I get involved in that?”

— John Nagy ’00M.A., an associate editor of this magazine.

Annemarie Reilly was 28 in 1994 when the call came to drop what she was doing in El Salvador and report for emergency duty in Angola. The southwestern African nation was embroiled in a seemingly endless civil war that was flaring up again. Within three weeks, the neophyte Reilly ’88 and two Catholic Relief Services (CRS) colleagues had hired 40 Angolans and were distributing food to 90,000 starving people in the besieged city of Huambo.

She was discovering her life’s work and was hating every minute of it.

“I didn’t know what I was getting myself into,” she says. Danger was imminent, everywhere. One day, as thousands queued up to register for the United Nations’ food program, Reilly saw people starting to run. Seconds passed before she heard the approaching engines — Russian-manufactured MiG jets. “Tiny planes, unbelievably loud,” and so imprecise you never knew where the bombs would fall, Reilly recalls. It was her first visit to Africa, her first direct experience of what people she served had to endure every day.

It wasn’t her last. When the relieved Reilly returned to her comparatively calm post in El Salvador, she realized her gift for making good decisions under severe pressure with limited information. “I just knew that this was it,” she says. “This was what I needed to do.”

“This” was international emergency response work: Helping people and local institutions in such desperate situations as civil war or the aftermath of a tsunami; acting “quickly to meet their basic needs, protect their human dignity, get [them] back on their feet.” Over the next 20 years, on behalf of CRS, the international poverty relief and development arm of the U.S. Catholic bishops, Reilly would journey to some of the cruelest places on earth.

Her conviction soon deepened in Burundi, where international aid workers were being murdered and where Reilly, now in charge as CRS’ country representative, celebrated her 30th birthday alone under night curfew in a house with no electricity. By contrast with Rwanda, its neighbor to the north, Burundi was suffering gradual ethnically motivated killings, what one observer described as genocide “drop by drop.”

Burundi taught her how to empower her colleagues to do their best work in dangerous environments, but she began to feel it was like reinventing the wheel every time CRS personnel stepped out of their customary programs to respond to a crisis. The agency needed to provide formal training and guidance. So, in 1997, CRS brought Reilly “home” from a posting in Liberia to its headquarters in Baltimore, Maryland, to become its first emergency response adviser.

Reilly’s travels were a sea change for a young woman from a big family that had “barely left the tri-state area” around their New York City suburb. While her father, Kirk Reilly ’55, had instilled in her a love of the arts, by high school she had set her sights on a foreign-service career. Then came Notre Dame, the Center for Social Concerns, and classes with political scientists Peter Walshe and George Lopez, economist Denis Goulet and theologian Father John Dunne, CSC, ’51. Reilly found her mind shifting from diplomacy to human development and her heart opening to the role her mother’s example of love and kindness might play in her career.

After graduating she volunteered through a new program for young ND alumni, the Puerto Rico Center for Social Concerns, where she met fellow volunteer Thomas Kelly ’88. Their paths strayed globally for years until — with Reilly working in Baltimore and Kelly new on the economics faculty at Vermont’s Middlebury College — they ended up at least “on the same continent.” But not for long. Reilly’s ideas soon took shape in the creation of a CRS Emergency Response Team, based in Nairobi, Kenya, where she moved once more in 1999. Kelly followed on a Fulbright in 2001, and the couple soon married on the Kenyan island of Lamu.

Reilly says her years leading the emergency team were the most rewarding of her career. The team went everywhere CRS could alleviate massive suffering: to Gujarat, India, to help earthquake victims in 2001; to central Africa after the eruption of Nyiragongo the following year. She estimates having worked in some 60 countries overall.

Family life — her elder daughter was born in South Africa — led back to Baltimore, where Reilly helped coordinate the agency’s response to the Haiti earthquake in 2010. Today, as CRS’ executive vice president for strategy and organizational development, plotting a more efficient future for the 5,000-employee agency that serves 100 million people in more than 90 countries worldwide, she reports to the president and CEO, former Mendoza College of Business dean Carolyn Woo. At CRS, she says, “We see ourselves as an expression of the love and solidarity that American Catholics have for the poor and vulnerable overseas.”

Meanwhile, Kelly is a collaborator in the fight against extreme poverty, serving on the senior staff of the Washington, D.C.-based Millennium Challenge Corporation. At their Baltimore home, attending to their younger daughter who is home sick from school, Reilly acknowledges the attraction of again serving directly overseas. Where? Maybe through the CRS office in Jerusalem, where peacebuilding is part of the program and Reilly could walk with the poor, following the ancient footsteps of the man whose life has most inspired her own.

— John Nagy ’00M.A., an associate editor of the magazine.

Anne Thompson ’79 time-shares her dog — she and a friend in Manhattan take turns caring for the same pup.

“I travel so much I can’t have a dog on my own,” she says.

Recent ports of call: Sochi, Russia, for the Winter Olympics; Charleston, West Virginia, to cover the chemical spill; Australia; Costa Rica; Japan; the Amazon; Greenland on three separate occasions.

And, regularly, Rome, for whatever significant event involves the Catholic Church.

Thompson is a 17-year veteran correspondent for NBC News whose high-profile beats have ranged from politics to finance and, these days, the global environment. The Church stories fell to her when her NBC bosses, who needed some Catholic expertise, heard she went to Notre Dame.

“I was in Rome for 38 straight days covering the resignation of Pope Benedict and election of Pope Francis,” she says. Nice duty, but, she adds, “I also lived in Venice, Louisiana, on a houseboat for five months.”

Thompson was covering the 2010 BP oil spill on that occasion, a story so compelling she led all NBC correspondents that year in air time. “I learned something every single day.”

Viewers learned a lot from her coverage of such stories as the jobless recovery, for which she won a Gerald Loeb Award for distinguished financial reporting in 2004, and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which brought her and her Nightly News colleagues a duPont-Columbia Award and Emmy Award in 2006.

Her role as chief environmental affairs correspondent provides both endless frequent-flyer miles and stimulation. “The environment affects every aspect of our lives,” Thompson says.

It also invites much vitriol. Reporting on climate change has exposed her to hostile blowback she has never before encountered. “I focus on the science, not the politics,” she says. “But we know the climate is changing. I think some people are afraid of change, especially economic change that would affect their livelihoods. I’ve covered politics and religion and never gotten this kind of nasty response.”

Still, she is doing what she set out to do: cover news on television. “This is the only job I’ve ever had, and I’ve been lucky to do it as long as I have.”

— Bill Carter ’71 covers the television industry for The New York Times.

A high school teacher once told Denise Umubyeyi she would never get into Notre Dame.

Umubyeyi’s journey to that suburban Chicago high school classroom had been a difficult one. When she had landed in this country a few years earlier, she had never written a sentence. Perhaps the odds were against her. But her teacher’s doubt spurred a stubborn determination.

“Well, fine. I’ll show you that I can,” the young woman recalls thinking.

Now a senior at Notre Dame, Umubyeyi is majoring in political science and enjoying the educational success her parents always dreamed she’d have when they gave up everything to leave Africa.

Umubyeyi was about 2 years old when her family fled their native Rwanda to escape the genocide. They moved to Tanzania, but soon political unrest there caused them to pack everything they could fit in a white pickup truck and cross the border into Zambia. The United Nations eventually relocated them to Glen Ellyn, Illinois.

Placed in an unfamiliar eighth-grade classroom, Umubyeyi could read but not write. Her British English didn’t equate to the talk of the Chicago preteens, and she remembers embarrassing moments of misusing words.

A volunteer at an after-school enrichment center took interest in the young teenager who was struggling to fit in. The woman relentlessly pushed Umubyeyi to write better. If she forgot one punctuation mark, Umubyeyi would have to start over. She also was introduced to classic literature, which she read voraciously.

Her writing improved steadily, and she wrote in a journal every day. Toward the end of her high school career, Umubyeyi was taking Advanced Placement classes and earning As.

The Notre Dame student now volunteers at the Robinson Community Learning Center, working for enrichment programs that emphasize writing.

She doesn’t know what she wants to do after graduating from Notre Dame but hopes to be an advocate for students who come from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“Once you learn how to read and write well, you can conquer everything,” Umubyeyi says.

— Madeline Buckley ’11, reporter for the South Bend Tribune.

When senior Tom White took the stage at Notre Dame’s DeBartolo Performing Arts Center for a “Creating Knowledge Together” TED Talk, he began with a quote from Monty Python: “And now, for something completely different.”

It might seem counterintuitive for someone with severe Tourette syndrome — which manifests itself in White’s case with physical tics and involuntary, often inappropriate exclamations — to volunteer to speak to a crowd of hundreds. But White, a self-described extrovert, enjoys connecting with others.

At age 10, White wrote a résumé for his future self for a class assignment. It detailed how he’d leave Long Island to attend Notre Dame, making him the first member of his immediate family to do so. Three years later, he began to show signs of Tourette’s, a second voice constantly fighting for control of his one body.

“Every single second is a battle. It wants me to say things, it wants me to do things . . . and it just mounts and mounts and mounts until something comes out.”

White, who has lived that battle for a decade, is a few weeks away from achieving his goal of graduating with the class of 2014, although his youthful prediction of his four-year term as the leprechaun proved less accurate.

While other students might be coasting as second-semester seniors, White is taking 19 credits — because he thought better of trying to convince the registrar to let him take 23. A double major in Italian and the Program of Liberal Studies, White is writing a thesis on Machiavelli, researching communism for a professor at the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, and maintaining the 500-page weekly reading load in PLS.

Outside of his classwork, White is a grinding winger on the club hockey team. He also maintains an investment portfolio with his younger brother, and our 9:30 a.m. meeting had to be pushed back an hour so they could hedge their positions during a 200-point sell-off. After graduation, he’ll work in the healthcare sector at Huron Consulting Group, which he sees as a vocation to help others who regularly deal with medicine and doctors.

“I know my Tourette’s is something you can’t ignore, but in a way it’s a blessing,” he says. “If people can’t see beyond that, I know they’re not worth my time.”

— Jack Hefferon ’14, this magazine’s spring intern.

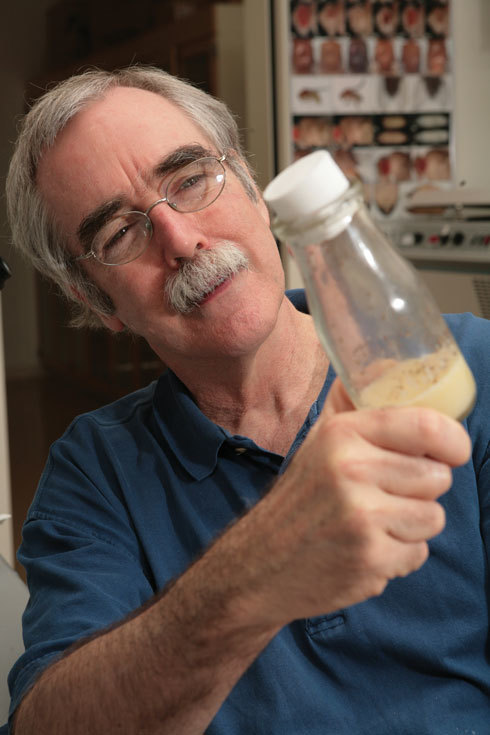

To earn spending money when he was a Notre Dame undergrad, Eric Wieschaus ’69 cared for the fruit flies in Professor Harvey Bender’s genetics lab. Were it not for Drosophila melanogaster, those flying specks that mysteriously appear when your banana goes bad, the ND grad may never have earned a share in the 1995 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. To his chagrin, the tiny insects, which he grew to loathe as he washed countless bottles in Bender’s lab, became the primary research tool throughout his career.

As a doctoral student at Yale and a research scientist in Switzerland, Wieschaus became fascinated with embryo development and used Drosophila to study the process. In a painstaking trial-and-error process that involved comparing thousands of mutant fruit flies in eight months of 16-hours-a-day work, Wieschaus and colleague Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard identified 139 genes that are crucial for normal development of the embryo. Until their work, no one had a clue how genes controlled embryo development. The Nobel committee took notice.

Since 1981 Wieschaus has been a member of the Princeton University faculty, where he continues to use fruit flies to study the genes that determine changes in embryo cell size and position.

With no regret, he has devoted his life to science. Other than family, Wieschaus says he has time for little else.

“Every morning when I go into the lab I think I’m going to do something wonderful,” the embryologist said in a 2013 video interview with a Princeton colleague. “I know I can do stuff and it will contribute to this whole of human knowledge that will live forever. I get the pleasure of doing it and figuring it out.”

— John Monczunski, freelance writer and former associate editor of this magazine.