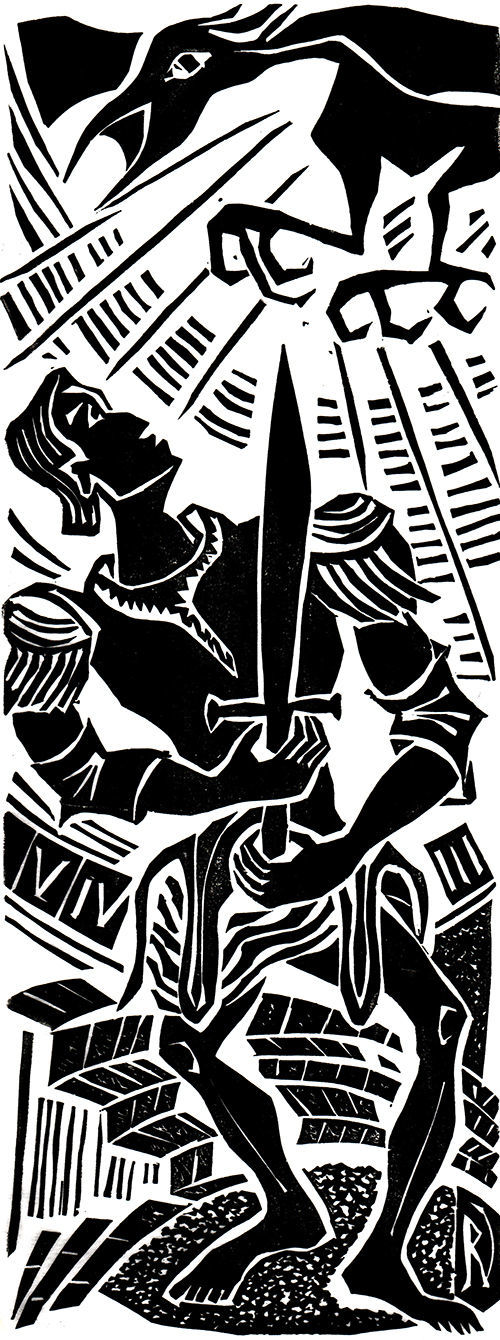

On a road in fourth-century Armenia, the story goes, a Roman centurion met a talking crow. The officer had resolved to convert to Christianity, and now the crow had come to ask him not to do anything rash, to defer his conversion for a day. The centurion, though, would not be put off. “I’ll be a Christian today!” he vowed. Realizing that the crow was, in fact, the devil in avian form arrived to tempt him, the centurion — who would later be venerated as Saint Expeditus, patron of procrastinators — stomped the bird to death.

I learned about Expeditus in the course of my research for this essay, research being one of my favorite ways to avoid actual writing. The fact that Expeditus is now believed not to have existed doesn’t keep worshippers from crowding services in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on his feast day or believers in New Orleans from praying to him for, among other blessings, the will to complete one’s work on time.

Unlike Expeditus, I have always been a procrastinator. This tendency makes me an easy mark, if not for talking crows then for many other tempters. The list of things I did when I might have been working on this piece, for example, includes reorganizing my underwear drawer; watching YouTube videos of someone else’s dog barking at a teaspoon; painting a radiator; inventing at least one new gin-based cocktail; vacuuming the stairs; shopping online for those great old Puma basketball shoes that Clyde Frazier used to wear; sweeping the kitchen floor unnecessarily; eating every last scrap of cheese in our refrigerator; trying, unsuccessfully, to repair a dripping faucet; and, my deepest, darkest shame, listening to sports talk radio.

Chances are good that you have your own techniques for putting off what needs to be done. Piers Steel of the University of Calgary, one of the more readable of the surprising number of psychologists, philosophers and economists writing on the topic, says that 95 percent of the population admits to procrastinating even when they know that they will be worse off for doing so. (Some of his fellow experts can be found at conferences on the topic, like the one at Oxford University that featured a “mañanarama” and such papers as “Idle Days in Baghdad: The Emergence of Bourgeois Time and the Coffee Shop as a Site of Procrastination.”)

Almost a third of U.S. undergraduates are “severe procrastinators,” according to a study cited recently on The New Yorker’s website. (Though I suspect that the current, earnest and service-obsessed generation of students is relatively incompetent at wasting time.)

Procrastination persists at work. One survey found that employees procrastinate away 100 minutes of every workday, accounting for losses of about $9,000 per worker per year due to reduced productivity. Economist David Laibson has pointed out that many Americans never get around to enrolling in retirement plans, thereby passing up vast sums of money in matching 401(k) contributions.

We put off getting married and having kids, too. The median married age has climbed since the 1950s from 22 to 27½ for men and from 21 to 26 for women. The Centers for Disease Control says the average age of first-time mothers rose from 21½ in 1970 to 26 in 2012.

Do these numbers mean that we live in a Golden Age of Hesitation? Is procrastination, as one academic article put it, “a malady for modern times”?

This procrastinator (married at 36, a father at 37) isn’t all that worried. I want to say a few kind words about procrastination. I want to argue that delay sometimes helps us see that some things aren’t worth doing. That dawdling sometimes turns into contemplation and then into creativity. That wanting to postpone the inevitable makes us human and more interesting. In his 1932 essay, “In Praise of Idleness,” Bertrand Russell railed against the “cult of efficiency.” I, too, want to applaud procrastinators for their mutiny against the rule of clocks and for their nonconformity amid all the methodical drones.

But it’s also true that I’m harder on other procrastinators than I am on myself. I certainly don’t want the EMT who someone someday calls on my behalf to be a dawdler. I get upset if my pizza delivery is even a little late.

Maybe it’s a comfort to know that the urge to procrastinate is nothing new, nor is the scolding of moralists and time-management gurus. The ancient world watched the clock just like we do. Steel has pointed to Egyptian hieroglyphs from 1400 B.C. that supposedly warn, “Friend, stop putting off work and allow us to go home in good time.”

Cicero, in an attack on his rival Mark Antony, warned that procrastination is “hateful,” especially in a warrior. His concerns were echoed 1,800 years later, during the U.S. Civil War, this time in reference to the Union general and infamous foot-dragger George McClellan. His fellow general Henry Halleck fumed, “There is an immobility here that exceeds all that any man can conceive of. It requires the lever of Archimedes to move this inert mass.” President Lincoln was characteristically pithier. He said McClellan had a case of “the slows.”

The Judeo-Christian tradition has little use for procrastinators, either. Listen to Rabbi Hillel: “Do not say, ‘When I am free I will study,’ for perhaps you will not become free.” I tried this ancient bit of wisdom on my 13-year-old son recently. He grunted and went back to posting on Instagram.

The New Testament is filled with admonitions to hurry up (“Settle matters quickly,” Matthew 5:25) and not put off the important stuff, like repentance. This accounts for my unshakable worry that by failing to patch the tear in one of our window screens in a timely fashion, I have sinned.

Not that the record of the early Church fathers is spotless in this regard. Saint Augustine, born not long after Expeditus is supposed to have been martyred, famously prayed for chastity, “but not yet.”

I’m not pointing fingers. Writers may be the world’s most persistent procrastinators, which is strange because in our trade the deadline is supposed to be sacrosanct. Author Douglas Adams said, “I love deadlines. I love the whooshing sound they make as they go by.” When he died in 2001, he was 12 years past deadline for his last book.

For some writers, procrastination is a kind of fuel. Geoff Dyer’s wonderful Out of Sheer Rage is a book about not writing a book about D.H. Lawrence. It is a masterpiece of indecision and distraction.

Writers are also unmatched at excusing their own sluggishness. Does anyone talk about “accountant’s block”? Does your auto mechanic claim to need a soulful, seaside stroll before he can get down to work? Even pacing the floor, that cliché of the creative act, is a kind of postponement. I used to think that when I paced I was summoning big thoughts, getting my mental gears going by putting the physical in motion. But maybe all that ping-ponging back and forth was just a simulacrum of my psychic vacillation, my irresolution: Should I sit here or sit there? Write this or write that? Should I even be a writer at all? Maybe there is a way for me to make a living that doesn’t require staring at blank paper, blinking cursors.

Some procrastinators blame their habit on perfectionism or fear of failure. The idea is that they can’t do anything until they know they’ll do it just right. But I suspect that simply having choices is what makes procrastinators of us. In the literature of indecision, no one has dithered as profoundly as Hamlet, the student prince and ancestor to today’s procrastinating undergraduates. If the old honor code of familial revenge had been good enough for Hamlet, his response to his father’s death would have been automatic. But Hamlet was a new kind of existential hero, which means that before he can do his job — killing the king, in his case — he has to agonize over who he is, what he is here for, the meaning of life, the mysteries of eternity. All of this is inconvenient, but it is what makes him one of us. He is undone by his own free will, by his choices.

This is why it is important not to confuse procrastination with simple sloth. Procrastinators aren’t necessarily lazy. Some of us accomplish a lot by not doing what we’re supposed to do. In his humor classic, “How To Get Things Done,” Robert Benchley writes, “Anyone can do any amount of work, provided it isn’t the work he is supposed to be doing at that moment.”

Still, like a lot of procrastinators, I am always alert to the things I haven’t got around to doing — the books not written, the Internet start-ups not started up. What bothers me about my procrastination is that I am not doing what some ideal version of me should be doing.

But for most of us, the things we do when we’re supposed to be doing something else end up being called our lives. The really dedicated procrastinator can create an entire identity out of the things he does instead of doing what he ought to. It’s not the most efficient way to live, but it’s more fun than always following the rules. If you think that people are defined by more than their resumé, then you are probably at least a part-time procrastinator.

If it’s true that procrastination can stunt us and frustrate our potential, it’s also true that it can be a way to realize ourselves and assert our agency. It can be self-defeating, but it can also be an opportunity to ask if the next item on the to-do list is really worth doing. Procrastination has a lot to tell us, if we bother to listen.

Yet procrastination remains a slightly guilty pleasure for me, because I fear that I am misusing my limited fund of time.

Just before I was due to file this piece I spent two days with my brothers and sister, standing around my mother’s hospital bed in Chicago while she took her last breaths. No one taught me more about work than my mother, and probably no one understood better my lifelong ambivalence about work. She would have shaken her head at some of my rationalizations, recognized them as a kind of excuse-making.

I paced a lot in those days in her hospital room, not knowing what to do but knowing there was nothing I could do. I paced just as I sometimes do when I’m writing an essay like this. My piles of notes for this piece were there, in fact, in the duffel bag I had brought with me from Brooklyn. There is nothing like a hospital room to remind you of clocks ticking, deadlines approaching. The urge to cure ourselves of procrastination, finally, comes from recognizing that time is passing, running out, and that it would be a sin to waste it. So the self-help section tells us to just do it. Buckle down.

But I want to believe that in our best lives we never get around to doing the big things we are meant to do. Rather, we do a million other things, inexplicably and in the interstices. And miraculously, some of them prove worthy and wonderful. You could try to break this habit, but wouldn’t that be a little like trying to cure the human condition?

Pacing and postponing, I’ll keep asking what I’m doing here. I’ll get around to figuring it out soon.

Andrew Santella (on Twitter @andrew_santella) has written for GQ, The New York Times Book Review, TheAtlantic.com, Slate and other publications. He is writing a book about why he has not yet written a book about the history of procrastination.