I love watching people pray.

The other night at dinner in Notre Dame’s South Dining Hall, I could not stop myself from staring at the guy beside me. Before he touched the meal in front of him, he closed his eyes and gently crossed his hands on the table. He whispered the grace, the corners of his mouth curling into a subtle, perfect smile. And I overheard him finishing his prayer in a whisper: “In the name of the Father, the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

Thirty seconds of sincere prayer is all I need to grow a crush on a completely random guy.

Growing up in China, an atheist country, I never prayed before family meals. We didn’t pray before breakfast, lunch or dinner. In contemporary Chinese culture, religion is usually considered a bewitchment of the mind and faith is regarded as the illusion that you have someone to depend on. I am not an atheist myself, but I find it extremely difficult to believe.

I have tried to pray. I don’t know why, exactly, but I have tried. Yet I have always found it extremely difficult. Whenever I close my eyes, I cannot stop myself from doubting everything I do: “Is it really God I am talking to?” “Will He really hear me?” and, occasionally, “Wait . . . is there really a God?” As far as I can remember, a solid “No” has always been my intuitive answer to those questions. And as I grow older, I have come to see there is nothing I can do about it. I was brought up in a culture that did not accept religious faith, and it is part of my identity. I simply cannot pray.

Maybe that is why I developed a sudden crush on South Dining Hall Guy. He prays, and I do not. He is a devout Catholic praying before dinner, and I am an agnostic with a growling stomach. There are huge distinctions between us, perhaps even irreconcilable ones. And yet I find a mysterious joy in those differences. I find that when I look at them with an open mind, when I am willing to suspend judgment, I can see beauty in them, the beauty of irreconcilable differences.

I still remember the first Mass I ever attended. It was August of 2013, my first year at Notre Dame, in Geddes Hall. I had been preparing for the Mass for months. I had already familiarized myself with all the obscure theological terms: “liturgy,” “Holy Communion,” “the Eucharist,” “the Nicene Creed” . . . everything needed for me to behave normally in a Catholic Mass. I thought that with concrete knowledge of Catholicism and good will, I could perfectly blend in for just one hour, reconciling my atheist cultural background with my presence at Mass.

I was completely and fundamentally wrong. When the priest began the consecration of the Eucharist, the people beside me began to kneel. One by one, my friends and fellow students fell to their knees. All of a sudden, I was the only person in the chapel still standing. Well, not really. The priest was standing, too. My head urged me to simply conform and kneel down. But then my mom’s words started to echo loudly in my heart: “Never, never kneel down to others!”

I should explain that kneeling in Chinese culture means absolute submission of human integrity, and I have been told this for 18 years. Suddenly my legs were no longer legs. They became two pillars of integrity and refused to bend. I stood alone in the chapel, with the priest. I was so embarrassed by my own failure to blend in that I didn’t dare to raise my head.

The moment seemed endless. But when I was finally brave enough to look up, my eyes met the priest’s eyes, and I saw him looking at me respectfully, with no reproach, as if I were just another human being, a normal human being with an equally beautiful soul. Then I heard the piano playing softly and the choir singing. The music flew into my heart, and my embarrassment was replaced by something completely different, something joyful and grateful.

My roommate was kneeling beside me. I saw that she was smiling as she prayed. I smiled, too, involuntarily. Suddenly I was glad I didn’t kneel down. I was happy that I chose to stand and express myself in my own way. At that moment, standing was the only posture in which I felt comfortable and fully respected as a human being. And only in that way could I truly appreciate the beauty of the Catholic Mass. Yes, there were differences; irreconcilable differences. I was standing while all others were kneeling, but that difference was not important anymore and could no longer stop me from seeing the beauty of Catholic faith and of our shared human integrity.

After my first “standing” Mass, I enjoyed the Catholic Mass more and more, and I thought I had discovered the way to deal with those seemingly irreconcilable differences. I could not wait to return to China to share my stories with friends and help them appreciate the beauty of Catholicism as I had experienced it.

I returned home to Beijing the summer after my first year at Notre Dame. I was excited by all I had learned and could not wait to tell Nina, my best friend in high school, about my newly developed appreciation for Catholicism. We met over fish dinner, and I poured out all my deep thoughts about religion and faith. Nina looked at me strangely. She did not see the beauty of the irreconcilable differences I was explaining to her but instead thought I had been bewitched by the Catholic education at Notre Dame.

I was frustrated. I tried to explain to my friend, to make her see, to convince her to understand in the same way I understood. None of it worked. I felt myself becoming angry with Nina, but at the same time I was angry with myself, with my failure to persuade Nina to take “my side.” Yet I didn’t want to give up hope. Nina and I have been best friends for six years, and we have never had any communication problems. Surely, I thought, I could make her understand. Finally, I put my hand on her shoulder, looked straight into her eyes and whispered the most encouraging, comforting and convincing phrase I had heard in my single year of theology education at Notre Dame. “Nina,” I said, “God loves you.” (As soon as I heard myself speak those words, I was even less sure of what I believed.)

She looked at me with a big smile, took my hand off her shoulder and said, half-laughing and half-serious, “Okay, sure. Now can we focus on this wonderful fish dish?” That last response shut me up. There was an irreconcilable difference between us, and it would not be bridged by my attempts to change Nina.

So we focused on the fish, and we talked about all the things we always talked about: the future of Communism, China’s leadership changes and the revolution we planned to start in Beijing. Once again, we communicated without barriers. Though Nina could not understand my sudden curiosity about Catholicism, and I her immovable belief in atheism, I could still sense the similarities between us, two human beings with the same good will. We still had the same grand and idealistic dreams. We still had the same passion for life and future. We still loved each other dearly. And that was enough to temper all irreconcilable differences between us.

Now, a year and a half after my awkward first encounter with the Catholic Mass, I still have no intention to be converted or baptized. But I frequently go to the small chapel in Lyons Hall and simply stand there and watch my friends praying. I still talk with Nina about my life here at Notre Dame and listen carefully to her perfectly logical responses. The reality is that there are irreconcilable conflicts in the world and they are probably going to exist for a long time. The question is: How can we each fight for our deepest belief with whatever we have but without demonizing those who hold equal passions on the other side?

Buddhism has a concept called “absolute see.” It means seeing without judging. Through the “absolute see,” we fully accept the world as it is and give up those useless attempts to change others or ourselves. Finally, we are able to truly face up to those irreconcilable differences in the world and start to appreciate them. The “absolute see” of the world does not ask that we change ourselves and abandon our deepest convictions. But it should humble us, temper our passions, make us realize our excessive self-righteousness, and compel us all to open our hearts and minds to new beliefs.

All of which brings me back to my crush on South Dining Hall Guy. I understand now my crush was not actually on the guy. I realize now that I was not drawn to his words or gestures or even to his subtle, peaceful smile as he finished his prayers. Rather, my crush, my feeling of pure happiness, was on that flashing moment when I accepted the common beauty of human beings shining through our irreconcilable differences. This conflicting world is beautiful, especially when we choose to fully accept it.

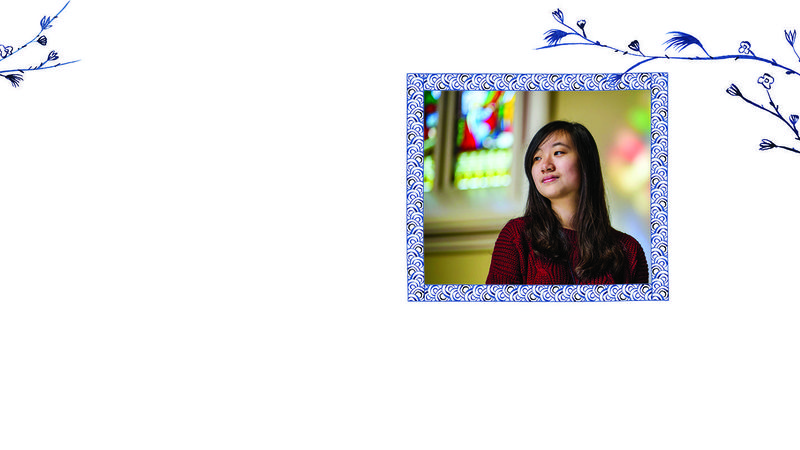

April (Dan) Feng is from Beijing, China. A sophomore at Notre Dame, she has a double major in political science and international economics.