I cannot recall the exact number of times I was prepped on “cultural shock” before I left for a semester in Rome in 2008. I was briefed on social differences, lectured on how to be reverent of a foreign society and reminded that, like Dorothy, I would not be in Kansas anymore. Four months later, however, there were no brochures or cutesy mantras to ease what was much worse: culture shock upon returning to the United States.

Sure, I knew that returning home to Phoenix would be light-years away from the neighborhood I lived in north of Vatican City, but these were changes I felt mostly ready for. My American peers and I joked about finally having ice in our beverages again, our groceries bagged for us, and catching up on episodes of The Office. And it is not as if we were immersed in an exclusive Italianate experience. Rome itself is “Americanized,” catering to the millions of tourists who dash through its museums every year; I even attended an American university in Rome. The Eternal City could be as Italian or American as you made it.

But I was shameless about shedding my American ways and diving head first into Italy. I enrolled in a high-level Italian literature course, where we read novels by 20th-century Italian female writers. I ambled up the street to our neighborhood pub several times a week, endeavoring to make new Italian friends over cigarettes. Marlboro Lights became my greatest social alleviant: They were an in, however brief and carcinogenic, to the social circles gathered outside Roman night spots.

Surprisingly, I found Italian youth were appreciative of my two-beer Italian and anxious to talk about American culture, though a little less excited to field my own questions about Italy. Francesca and Roberto and Lorenzo alike did not understand why I would rather talk about Berlusconi in the upcoming elections than fight over the best Beatle (why I chose George over John mystified them, but some things transcend cultural differences). During my semester’s worth of morning visits to the coffee bar by school, Lucia and her son Alessandro learned I always had my caffè macchiato. And in May, Alessandro winked as he snuck some homemade cream into my tiny espresso cup. The mark I had made it. I was a regular, and I was living the dream.

However reluctant I was, and still am, to admit this, traveling around Italy for four months with academics as a sort of an extracurricular is, sadly, not reality. I eventually had a 767 flight landing in the capital city of Reality, USA, and had to say goodbye. Arrivederci to my espresso mornings, my 40-minute cobblestone walks to school, and a country that taught me how to slow down and look around (the better to see life and its relationships, not to mention the five oncoming Vespas).

So there I was, in my first hours back in American reality, staring down at the sin of all sins: a to-go coffee. I looked down at the Starbucks espresso cup and could not fight the rising riot in my stomach as I drifted away from the bustling counter in Dulles Airport. They have it all wrong. We have it all wrong. An espresso . . . to go? Lucia and Alessandro would turn up their noses at such a thing. Yet there I was, toting my coffee to gate C12, holding in my hand the most tangible difference between American and Roman life.

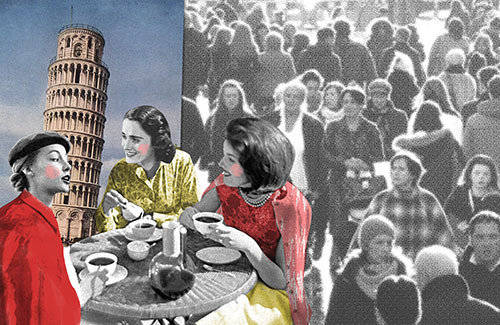

For Romans, a morning and afternoon caffè is part of the day but by no means an anxious necessity. There are no signs of the desperate coffee runs we are familiar with in the States, as the low-rung intern balances two trays of grande-no whip-nonfat mochas across the parking lot. Here, executives chug their house blend with a wild-eyed urgency, as if the Styrofoam contains their very lifeblood for the rest of the working day, for the week, for the year. Not in Rome. I have stood between a street cleaner and a museum curator at Lucia’s bar, both carefully accepting their saucer and espresso cup with a calm sort of reverence.

My purpose here is not to paint Rome as an elegant world where beautiful Italians sip their coffees and ask, “How is the family, Giovanni?” with a magazine smile. I overheard grumbled reminders of the money owed to Pietro, countless fights over the rival Roma and Lazio soccer teams, and one Italian grandmother crazily insisting her terrier have a caffè freddo as well. But all the customers shared the same experience: to pause at the counter, if only for five minutes, before continuing on. I cannot imagine what Lucia would scream in Roman dialect if I were to tell her that Americans no longer even have to exit their cars; the concept of drive-thru coffee would probably end her on the spot.

“I can’t drink take-away coffees, Mom,” I whined two days after returning home to Phoenix. My parents had dealt with my Italian elitism with grace, accepting that every sentence for the next few months would begin with, “This reminds me of that one time in Lake Como” or “They do it so much better in Florence.” As my mom whisked up her keys and purse before rushing off to work, she proffered a solution. People sit and enjoy their coffees at the local AJ’s every morning, she said. It seemed quite removed from but the closest I could get to a Roman cappuccino. I had become the desperate, jilted lover who would take even the slightest whiff of cologne to carry on. Next stop: AJ’s Fine Foods.

Never mind the actual ordering of the coffee. I cannot discuss my internal crisis when faced with a house blend called Caramel Pecan Supreme. That morning was more about an attempted emotional return to what was: taking a time-out for coffee. And there! On the shaded patio of AJ’s was a promise of perspective, three women in their mid-30s whose coffees confidently rested on the wrought-iron table. I sat just barely still in earshot as I glanced at the trio. Perhaps they understood the value of slowing down, even in the midst of the Scottsdale frenzy. Their conversation threaded through pregnancies, parties, a great new bistro down on 44th and Grey’s Anatomy to Peter’s law practice, the days of playing golf once a week are gone and Joe carving out time from the office. More than the conversation’s content, I was focused on the reason these women — and even I — were able to linger.

In America, a sit-down coffee is a luxury. These women led lives that allowed for a certain sort of idleness. My parents and their hard-earned livings allowed for my education, my post-abroad-elitism and my own morning of idleness. My pre-Roman self would frown at this word: idleness. Surely, I cannot be judgmental enough to classify a sit-down coffee group as idle people. Idleness is akin to an insult in our society, an indication of a lack of drive or intent, of someone who is not overly concerned for their own well-being or that of society. There are deadlines, there are overheads, there is no time to linger. That is, unless, you’ve earned it. Your hard work can earn the luxury for downtime, the luxury for vacations and pleasure cruises, the luxury of a sit-down coffee at a wrought-iron table in the sun.

Is that American life today? Is it the Visa commercial from a few years ago, where the bumbling person who pays in cash (and not the company’s shiny swipe-and-go innovation) is criminalized? The one where the music stops and there are no more costumed leaps across the neighborhood bakery, all because someone has messed with the consumer rhythm. Don’t be that person, we think to ourselves, the person who brings the doo-wop beat to a screeching halt. Move faster, work harder: Everyone’s still smiling, right?

But lo and behold, after my sit-down coffee, I would become the embodiment of the Visa commercial antagonist. Live in living color, stopping the oh-so-catchy American consumer beat, guilty as charged.

Let me first say: I never appreciated how gargantuan U.S. supermarkets are until I experienced the cramped market groceries abroad. I fought the urge to sit down in the middle of the Fry’s frozen food aisles (there are eight, by the way) and rock back and forth until my heart stopped racing. Dramatic indeed, but I came in through automatic doors for milk, and there I was with the onset of a panic attack.

It gets worse. Not even an American saint would excuse my behavior that fateful day in the check-out aisle: the express aisle. I casually dug through my purse for exact change, a courtesy in Italy expected by cashiers but a waste of everyone’s time here. The woman behind me audibly huffed at the 20 seconds I had snatched from her day, 20 seconds she would never regain, 20 seconds for which I should have personally apologized. As I scuffled away, dejected after my express-aisle trauma, I recalled the average 25-minute wait in the line of the supermercato. Twenty-five minutes, that is, until the two Italian grandmothers cut you in line. There’s nothing you can do about that, and you certainly wouldn’t be caught dead huffing at them.

Yet after the semester-abroad pixie dust settled and I sped into the future, that express-aisle day became only a distant memory. I have let out more than a few huffs in the grocery checkout. I have laid on my horn at the newly green light, mumbling curses toward the driver who added five seconds to my commute. I have snatched back precious time by fast-forwarding through the Visa commercials in my already-TiVoed Law and Order episode.

My Italianate sensibilities could not all hold strong, and clinging to them in America would have been as ignorant as throwing them by the wayside. But I hope that I haven’t forgotten the larger picture. We do not have to march to the faster, more efficient, on-the-go American beat. It would be tragic if we went on believing we had to merit, to somehow earn, the luxury to linger with a coffee. If we idle five minutes, if we don’t accomplish those three other tasks, will the music really stop?

Katie Palumbo Shinnick is the assistant principal of a Catholic elementary school on Chicago’s southwest side.