Somewhere around the time I became a teenager in the summer of 1962, I attended an Old-Timers’ game at Memorial Stadium in my hometown of Baltimore. The only thing I remember about it was my puzzlement at the way the old-timers ran the bases. They looked odd, almost comical, swaying left and right. Like ducks, I thought.

Now, more than half a century later, I understand that arthritis was the probable cause of the peculiar locomotion. Now the arthritic duck is me. I have two artificial hips, for which I am grateful every day. Before I got them, I had the mobility of the Tin Man — rusted tight until Dorothy grabbed an oil can and lubricated him for the trip to Oz.

And now I can tell the story of my own trip to a land of wonders. In January, while my neighbors in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C., were suffering through another snowstorm during the interminable winter, I was stepping off a bus from the Sarasota airport into the sunshine drenching the Buck O’Neil Baseball Complex, part of the Florida spring-training home of the Baltimore Orioles.

I looked past the palm trees to a wall that was an Orioles Mount Rushmore in paint. It carried the images of six Baltimore immortals: Brooks and Frank Robinson, Jim Palmer, Eddie Murray, Earl Weaver and Cal Ripken Jr., each a Hall of Famer. At the age of three score and five years I had come as a participant in the Orioles’ annual Dream Week.

I came in the spirit described by Frank Deford, a member of the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association Hall of Fame and a son of Baltimore, who wrote: “If you really care for a ball club when you are young — really care — I don’t think you ever get it out of your system, wherever you go, whatever the team does. It’s like any first love, a fantasy you see all the more precious through your imagination’s rear-view mirror.”

This deep loyalty to the hometown team is one of baseball’s great fascinations. It not only ties individuals to the team, it binds entire cities and regions together. Psychologists say such emotional instincts are part of our evolutionary equipment for forming large societies that cohere around great rituals and ideals that affirm our righteousness against rival groups. That’s why Orioles fans can call up at will the glory and euphoria of World Series triumphs in 1966, 1970 and 1983, while repressing memories of defeats in the World Series of 1969, 1971 and 1979.

The Orioles are a big part of my old hometown’s identity. So what a thrill it was to walk into the clubhouse in Sarasota and find something amazing waiting for me: Hanging from a hook in a hardwood cubicle was an Orioles jersey with my last name on it. I stopped to soak up the moment then texted a photo to my wife. The message: “When I was a kid, I KNEW this would happen.”

That’s why another name for Dream Week is fantasy camp. This one is a bucket-list indulgence, especially for me and the 10 campers older than my 65 years. It’s part of the process of negotiating a compromise — surrendering gracefully the things of youth and refusing to go gently into that long postseason.

We are at the far end of the camp’s age distribution, which the Orioles have defined as beginning at 30 and ending when the last dog dies. Our group of 114 men and three women included seven in their 30s; 45 in their 40s; 41 in their 50s; 19 in their 60s; and five in their 70s. The oldest, a 77-year-old retired dentist, came to camp with his 70-year-old best friend, a cardiologist he met after being rushed to a hospital with a heart attack. That was four decades ago. He is still going strong.

The Orioles charged a little over $4,000 for a package that included mid-January batting practice indoors at Oriole Park at Camden Yards, a round-trip flight from Baltimore, most meals, use of a clubhouse loaded with exercise equipment, daily laundry service for our uniforms, and access to trainers gifted in the art of tending the pulls, strains and pains that would have campers lined up at the training room every morning and night. Coolers were stocked with beer and soda, and buses shuttled us to our resort hotel on the beach of Lido Key.

Most of us probably had gone through a calculation that Cornell psychology professor Thomas Gilovich described last year to The Wall Street Journal. While some people choose to spend their money on items they can keep for years, others go for experiences. “We adapt to our material goods,” said Gilovich. Experiences, however, are more psychologically satisfying because, as the story noted, they can be “shared with other people, giving us a greater sense of connection, and they form a bigger part of our sense of identity. If you’ve climbed in the Himalayas, that’s something you’ll always remember and talk about, long after all your favorite gadgets have gone to the landfill.”

Dream Week’s principal activities were the 10 games — one every morning and one every afternoon — played by the 12 teams into which we were divided. But for many of us, those were the shiny gadgets, and the week’s highlights were the opportunities to socialize with the two dozen former players who had come to coach us while renewing their bonds with each other.

The oldest, looking remarkably good at 80, was Jim Gentile, who ruefully described the indignity of having to haggle with Orioles management for a $30,000 contract after hitting 46 home runs in 1961. Many were veterans of the 1983 team that battled through one of the most dramatic, maddeningly inconsistent and ultimately triumphant seasons in the history of the O’s.

That was the season of Orioles Magic, when they persevered through two seven-game losing streaks, won their division and then stomped the White Sox in the American League Championship. A week later they celebrated their World Series win against the Phillies in the usual champagne-drenched locker room where catcher Rick Dempsey — the Series MVP and now a Dream Week coach — took a call from the White House and told President Reagan, “You can tell the Russians we’re having an awful good time over here playing baseball.”

Baseball and Baltimore

In 1957, when I began playing Little League, the Orioles had a rookie third baseman named Brooks Robinson. He was a man of surpassing social as well as physical graces who played his entire 23-year career in Orioles orange and black, and made baseball’s All-Century Team. In an era when slugger Reggie Jackson moved from town to town, getting a candy bar named after him and becoming the prototype of the mercenary genie released by the onset of free agency, Brooks stayed with his team. Wrote Gordon Beard of the Associated Press, “He never asked anyone to name a candy bar after him. In Baltimore people name their children after him.”

To understand the importance of the Orioles to Baltimore, it helps to understand a little local history, including two Baltimoreans whose baseball careers streaked across the national sky, an HBO dramatic series, a depressing Randy Newman song, and Oriole Park at Camden Yards. These touchstones explain the city’s pride as well as its insecurities.

We Baltimoreans love the fact that during the War of 1812, after the British burned Washington, they sailed a bit farther up the Chesapeake with similar intentions for our town. Fat chance. They were pushed back in the Battle of Baltimore, during which Francis Scott Key, held prisoner in a British ship off Fort McHenry, celebrated the city’s resilience with a verse about a star-spangled banner that was still waving after the bombardment had ended and the Brits had sailed away. Now when the national anthem plays before a game, the crowd roars the “O” in “O say can you see.” We are the O’s.

That story from two centuries ago is proudly fixed in the historic and psychological self-perception of my city. It has fought off what seemed to be a death spiral of urban decline by redeveloping a huge, rotting industrial landscape through the never-say-die determination of William Donald Schaefer, the city’s mayor in the 1970s and ’80s. In cooperation with some visionary developers, he transformed the Inner Harbor to the gleaming source of local pride that draws admiring visitors from around the world. The American Institute of Architects called it “one of the supreme achievements of large-scale urban design and development in U.S. history.”

But the Inner Harbor’s vibrant yin is paired with a Dickensian yang down the street. It’s the Baltimore Randy Newman wrote about nearly 40 years ago in the baleful ballad that carries the city’s name: Hard times in the city/In a hard town by the sea/. . . And they hide their faces/And they hide their eyes/’Cause the city’s dyin’/And they don’t know why.

Written in the 1970s, Newman’s dreary anthem confirmed a view of Baltimore that millions of travelers still see as they pass through town. That is because Amtrak’s line between D.C. and New York runs past block after block of diseased neighborhoods hollowed out into ghostly shells of brick and despair. This is the Baltimore often seen on The Wire, the television drama created by a former reporter for The Baltimore Sun.

One critic, who taught a college course titled " The Wire as American Noir,” described it as “Greek tragedy writ across a modern American City.”

The tragedy came horrifically to life in late April, when riots ripped through neighborhoods familiar to viewers of The Wire. The circumstances that bred the violence have received intense scrutiny, with the political left pointing to police brutality and social injustice, and the right citing the absence of fathers in the lives of so many young black men.

As someone whose family has deep roots in a neighborhood that is now a blighted ghetto, I care deeply about these issues. But this article, drafted weeks before the violence that shook the city and stunned the nation, is about baseball in Baltimore. So for now, I’d like to turn to Babe Ruth and Cal Ripken and Oriole Park at Camden Yards. Let’s talk about how Baltimore saved baseball.

George Herman Ruth was born in 1895 to parents who a few years later found him so unruly that they packed him off to St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys. It was a combination reform school and orphanage run by the Xaverian Brothers, one of whom, Brother Matthias Boutilier, soon discovered that he had a baseball prodigy on his hands.

Everyone knows that Babe Ruth transformed the game with his titanic home runs. Most aren’t aware of Ruth’s heroics in pulling the game from the public wreckage caused by eight members of the Chicago Black Sox accused of throwing World Series games in return for payoffs from gamblers. As baseball historian and documentarian Ken Burns wrote, “After the 1919 Black Sox gambling scandal corroded trust in the sport, baseball was rescued by the advent of the incomparable Babe Ruth.” The Babe — aka the Sultan of Swat, the Caliph of Clout, The Great Bambino, the Big Bam, the Wazir of Wam — gave fans a reason to believe again.

Seventy-six years later, after the game had suffered the disillusionment of the players’ decision to walk off the field rather than accept the salary caps demanded by owners, it needed another redemptive jolt. The strike played out like a tawdry tale of greed and ego in a country increasingly worried about the great divide between the super-rich and the rest of us. Ripken dispelled that disillusion with a glorious run as the Iron Man, a superstar with a lunch-bucket ethos and a love for the game.

The September 6, 1995, nationally televised celebration of Ripken’s 2,131st consecutive game, breaking Lou Gehrig’s record, was one of the most cathartic and euphoric moments in baseball history. It gave Ripken a place close to Ruth in baseball iconography and the story of Baltimore. Burns wrote, “It is baseball’s rare good luck that both times the modern game seemed in mortal peril, it has been saved by the achievements of an extraordinary individual from Baltimore.”

Burns also saw a continuation of Baltimore history with the beginning of a transformational era of baseball-stadium architecture. “It all started in Baltimore, naturally, with Camden Yards,” he wrote. “The Orioles’ new park was the progenitor of a style that came to be known as ‘New Major League Classic,’ a deliberate attempt to evoke the beloved original concrete and steel ballparks built in the 1910s, unlike the multiple-use cookie-cutter suburban stadiums that had proliferated in the 1970s.”

Paul Goldberger, architecture critic of The New York Times, hailed the ballpark as “a building capable of wiping out in a single gesture 50 years of wretched stadium design. . . . This is a design that enriches baseball, the city and the region, all at once.” It miraculously transformed baseball architecture, ending an era of monstrously clumsy stadiums. Said Bob Ryan of The Boston Globe: “It is a ballpark that asks the question, ‘How could people have been so flat-out stupid in the 60s and 70s?’ City after city constructed horrifying concrete mausoleums, each one more boring, ugly and numbing than the last.”

Fantasy vs. anatomy

Speaking of stupid, it’s time to acknowledge the event that harshed my Dream Week mellow.

The warnings were in the air, carried by soft whispers and confirmed by silent shakes of the head. One told of a former camper who broke two ribs stepping off the bus from the airport. Another featured a guy who fractured his wrist diving back to first base. Others concerned diverse dramas of muscle, ligament, cartilage and joint. The word went out to dial our exertions back. Its most concise formulation was a wry aphorism: “Start slowly, then taper off.”

Bill Stetka, the camp’s amiable director, waved the caution flag at our first group meeting in the cafeteria where we had a fine breakfast and lunch every day. “Nobody is being scouted,” he admonished us. “Nobody needs to blow up his hamstring on the first day.” He laid out the rules intended to minimize pounding for those of us with compromised skeletons. There would be liberal use of “courtesy runners,” for example, so batters wouldn’t even have to run to first base.

But alas, Stetka’s Monday morning warning couldn’t forestall my folly, which had presented itself on Sunday afternoon, after we had donned our uniforms, loosened up with group calisthenics and fanned out to shag flies or take grounders. It was a sort of scouting minicamp. The former players who would coach the teams took notes they would use to arrange an even distribution of talent and age in that evening’s “draft.”

I took my position at third base. That was my first mistake, the tragic flaw of hubris amplified by an absence of geriatric self-awareness. I was an old guy remembering a young right arm. It had thrown a no-hitter when I was 12. When I was 17 and my batting average had sagged as the speed of pitchers had accelerated, my arm and glove were my only dependable tools, and they allowed me to play at third or behind the plate. Even when I was 45, I won 85 dollars — five dollars each from 17 colleagues in the Arizona Republic newsroom who bet I couldn’t throw a football 50 yards.

Before Dream Week, I had tried to prepare my arm despite the limitations imposed by winter. Mostly I tossed a lacrosse ball against a wall in an alley behind my office in downtown Washington, D.C. I was following an old pattern: loosen up the shoulder and you are good to go. But on this day, my shoulder was not the issue. I was about to receive a lesson in anatomy, specifically about an aging body’s loss of elasticity.

I joined four or five other guys on the infield dirt at third. We joked about the oceanic distance over to first base. Someone suggested we put a relay man by the pitcher’s mound. Someone wondered if the rule for courtesy runners could be expanded to allow for courtesy throwers.

Like some of the other guys, I heaved my first throw to first on a bounce. For my second grounder, I moved up on the infield grass, fielded the ball, shifted it to my right hand, cocked my arm and brought it forward — a sequence my arm had performed tens of thousands of times. Then came my introduction to the cruel reality that as we get older, our muscles — along with other tissues — lose elasticity, the simple ability to accommodate strain.

My arm traced its arc toward the release point. When it got there and my wrist began to snap forward, something like an ice pick stabbed the inside of my forearm, just below the elbow. The ball dived and careened toward second base, like a pheasant winged by buckshot skittering into the brush. I loosed an involuntary scream.

The pain was bad. The embarrassment was worse. The Orioles trainers would tell me what an MRI would confirm. I had torn the flexor pronator. It was a muscle I had never heard of, a name that sounded as sinister as it was strange. It made me think of Lex Luthor, comic book megavillain and Superman nemesis. It had brought me low for the sacrilege and absurdity of trying to play Brooks Robinson’s position at age 65.

I was stunned, a little depressed and self-pitying. My arm had betrayed me, I thought. It had gone over to the dark side, joining the conspiracy of my arthritic hips. Was this how Caesar felt in his fatal final game against the senators in Rome? Et tu, Brute? You too, right arm?

But the arm I was lamenting wasn’t just a remnant of my long-lost claim to mediocre athleticism. The ability to throw is basic to our identity as human beings, as Homo erectus. As an article in the Journal of Anatomy notes, “the hominid lineage began when a group of chimpanzee-like apes began to throw rocks and swing clubs at adversaries . . . this behavior yielded reproductive advantages for millions of years, driving natural selection for improved throwing and clubbing prowess.”

So don’t ask for whom the flexor pronator tears. It tears for thee. Mine had ripped like a rusted cable on a suspension bridge, plunging my fantasy into the depths of Sarasota Bay. Within a few hours the internal bleeding and swelling had turned my entire forearm into a thickened Technicolor mass of red and purple and orange and black. I emerged from my next trip to the trainers’ room with a bulging plastic bag of ice hanging from my elbow like a feedbag.

Fortunately, the blown arm was the only bad thing that happened to me during the week. It was followed just a few hours later by the best thing.

At the camp’s opening dinner Sunday night, when the results of the draft were announced, I learned that I would be a member of Dempsey’s Dippers. That was the team coached by Rick Dempsey, the fiery, tough, funny catcher who was my favorite Oriole in the generation that followed Brooks Robinson. Sportswriter Richard Justice said Dempsey became “one of the most popular players ever to wear the [Orioles] uniform . . . by diving for foul pops, blocking the plate and throwing out base runners, by being a blue-collar guy in a blue-collar town.”

On Monday morning, I overheard Dempsey tell his assistant coach, former Orioles pitcher Dave Ford, that the team had already had a casualty. “It’s this guy Kammer,” he said, pointing to his clipboard. “Blew his arm out.” I told Dempsey I’d like to play and that first base might work. So he penciled me into the lineup for a few innings in a few games. I got a couple easy assists on ground balls. At the plate I was terrible. My biggest contribution to the team was a walk that loaded the bases and was followed by yet another walk that brought in the winning run. By Thursday I gave up the charade and watched the remaining games while sitting on the bench in street clothes.

So there wasn’t much fantasy on the field for me. But there were plenty of wonderful moments. Some came in the after-breakfast meeting, where there was an abundance of playful banter among the players and the coaches, who were awarding the symbolic gold ropes for outstanding individual performances as well as brown ropes for conspicuous achievement in screwing up. The brown ropes were more fun. One went to a catcher whose failure to catch a pitch allowed it to drill the umpire in the shoulder. Another went to a guy whose effort to cover second base for a force out came to an abrupt end when he tripped over the bag and “went down like he was hit by a sniper.”

An evening with Dempsey

My favorite part of Dream Week was the customary evening when each team treats its coaches to dinner, and the coaches reciprocate by treating the team with stories of old. Our evening gave us the chance to hear from Rick Dempsey, who passed around his 1983 World Series ring. Here are three Dempsey nuggets:

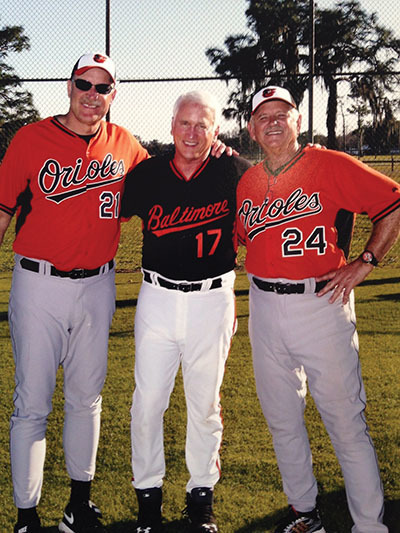

About catching Jim Palmer, the Hall of Fame pitcher (who appeared at camp for a few hours and had his picture taken with individual campers and his old teammates), “When the count was 0 and 2 he would say, ‘Call for a fastball, low and outside, and put your glove up about an inch from the corner.’ So I’d do it, and I could catch the ball with my eyes closed. That’s how good his control was.”

On playing for Earl Weaver, the irascible manager legendary for both his berserk encounters with umpires and sometimes his own players, and for his ability — well ahead of the statistical compilations chronicled in the book Moneyball — to draw maximum advantage from match-ups and situational analysis: “Earl was an ass, but he was the greatest manager I ever played for.”

On why he participates in fantasy camp: “I love it that you guys love the game enough that you’re willing to come down here and make fools of yourselves.”

Dream Week was indeed a wonderful week. What I appreciate most was that it strengthened my connection to the team, reaffirmed my identity as part of the city it represents. Those feelings had lost some of their elasticity during the Orioles 14-year losing streak that was induced in 1998 by Peter Angelos, the man Sports Illustrated would identify as the worst owner in baseball. But now Angelos seems to have brought stability out of the chaos, largely through the hiring of Buck Showalter as the manager and Dan Duquette as the general manager. Last year the team won the AL East.

I have only two regrets about the week. First, that I didn’t ask Mike Boddicker to show me how he threw the “foshball” — the forkball-change-up hybrid he used to whiff 14 bewildered and hopeless White Sox in Game Two of the 1983 AL Championship Series. I could have initiated contact many times but just didn’t want to intrude. We did have a conversation one day, as I walked past him in the clubhouse. I remember every word:

Boddicker: Good morning.

Me: Good morning, Mike.

The second regret should be obvious: I wish I had come to fantasy camp 20 years ago, when I was a young man of 45.

Jerry Kammer, a senior research fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington, D.C., lives in Rockville, Maryland. He previously was the Northern Mexico correspondent for the Arizona Republic, and in 2006 he won a Pulitzer Prize for his work on a Copley News Service team that exposed a political bribery scandal.