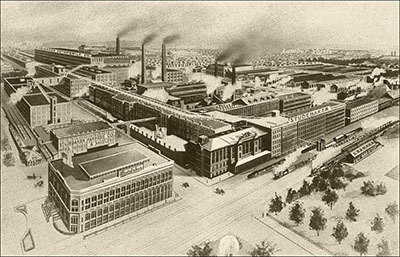

In 1852, Clement Studebaker and his brother started a blacksmith forge in South Bend, Indiana, with assets of $68 to their name. Over a half-century, the family business grew into the world’s largest maker of horse-drawn wagons and buggies. Studebaker sales were nearly $3 million in 1897 when Clement’s son informed him that times were changing.

“We better produce a motor car or we’ll be ancient history,” said Clement Jr. “Nonsense,” his father replied, according to one company historian. The horseless carriage was a “novelty,” and no carmaker had made even $300 that year. But the younger generation kept pushing, and Studebaker produced its first automobile within a year of Clement Senior’s death in 1901. His brother John, the last of the founders, still wasn’t convinced, pronouncing motor cars “clumsy, dangerous, noisy brutes which stink to high heaven, break down at the worst possible moment and are a public nuisance.” Yet John presided over the company’s timely transformation.

- Related article

- Putting South Bend enFocus

There were more than 5,000 makers of horse-drawn vehicles in America at the turn of the 20th century, but only Studebaker made a successful transition to manufacturing automobiles, driving their business and the country from the agricultural era into the industrial age. Sure, Studebaker shut its doors in 1963, putting 7,000 people out of work, but its century-plus run was remarkable for adapting to monumental change.

Today, a group of entrepreneurs and leaders in South Bend is taking aim at a similar and ambitious dream: Transform the Studebaker legacy, an industrial eyesore and symbol of bygone glory for the last 50 years, into a bustling hub for the high-tech data and cloud-computing businesses of the future. They believe the same fundamental components of geography, infrastructure and invention that helped Studebaker put northern Indiana on the global map can lead to another rebirth, dragging the region from the rusted era of manufacturing into the technology age. Fueled in part by Notre Dame’s growing research and commercialization efforts, a nascent success story is slowly turning around the Bend.

“South Bend has a gift for reinventing itself,” says Mayor Pete Buttigieg, a 33-year-old Harvard graduate and Rhodes scholar. “Drawing on Studebaker’s historic example, the city’s economic comeback reflects the innovative spirit that drove its proud past.”

A quick list of recent progress hints at the potential. Data Realty, a data management company, became the first to progress through the pipeline from Notre Dame concept to off-campus incubator to a technology park arising on former Studebaker land. At 140 acres and 4 million square feet of old factory space removed, the Studebaker Corridor is among the largest brownfield remediations in the state, and plans just taking hold could turn it into a significant economic redevelopment project. F Cubed, a DNA diagnostics company, is preparing to move into one of two buildings under construction there now. The other new building will become home to the Notre Dame Turbomachinery Facility, where research and testing on gas turbine engines is expected to draw companies supporting the aerospace industry.

When it comes to turnarounds, perception is everything. If you start at the airport and drive toward downtown and the failed College Football Hall of Fame, the trip includes dilapidated buildings spotted with liquor and check-cashing stores, closed industrial businesses and boarded-up homes.

But try another route: Start south of Notre Dame with the high-tech incubator at Innovation Park, browse the stores, restaurants and apartments at Eddy Street Commons with its college-town feel, drive by the beautiful new homes in the Triangle and on Notre Dame Avenue, turn right at the new St. Joseph High School, view the new riverside restaurants and apartment complexes by the East Race, stop downtown for lunch at the rehabbed bank building that Café Navarre calls home, tour the bustling Internet carrier hotel that Union Station has become and end at Ignition Park, where the legacy of Studebaker laid the foundation that tech companies need: cheap space, plentiful power and transportation routes that became the information superhighway.

The difference between these driving paths explains how Newsweek could include South Bend on its list of America’s Dying Cities in 2010, yet Cisco’s Smart + Connected Communities initiative could place South Bend in its 2012 list of Cities in Transition, alongside Barcelona, San Francisco and Rio de Janeiro.

“I had some folks in from Chicago who hadn’t been here for a few years,” says Rich Carlton, president of Data Realty. The group stayed at the rebuilt Morris Inn and took the second route through town. “These guys were blown away. They couldn’t believe the changes they saw.”

City-tracked statistics reveal dramatic differences. Private investment in South Bend leaped from $29 million in 2013 to $180 million last year. New jobs announced in that period quadrupled from 330 to 1,368. Ten years earlier, fewer than 200 new jobs were announced.

Three major factors have sparked the turnaround. Notre Dame’s investment in research has recently exploded into a commitment to commercialize — to turn intellectual capital into marketable products, often made nearby. In demographics, the desire of empty-nest Boomers and mobile Millennials to live in cities instead of sprawling suburbs has revived prospects for urban-core redevelopment. Third, the city’s location south of the Great Lakes and along a corridor that runs north of the Appalachian Mountains means the region’s highways and railroad easements make it one of the densest corridors in the country for transcontinental fiber-optic cables, the backbone of the Internet economy.

Change didn’t come from outside factors alone. Past city leaders have paved the way with some hits and misses, but Buttigieg, the first South Bend mayor born after Studebaker closed, is slowly convincing people to simultaneously celebrate the past and let it go.

“Often times, community development is an ‘overnight’ success that’s been 30 years in the making,” says Scott Ford ’01, ’09M.Arch., the city’s director of community investment. “The same fundamental tenets that made this region attractive to the pioneers are still in place today, especially in terms of transportation and logistics. We have an excellent history of manufacturing, a culture of productivity, plus a tremendous resource in a world-class university at a time when people are rediscovering cities. I think South Bend is poised.”

###

Perhaps no single story better exemplifies this small-city tech explosion than that of Kevin Smith ’78, whose goal is to turn the last large Studebaker industrial building into a beehive of high-tech businesses.

The dilapidated, six-story Assembly Building — also called No. 84 or Ivy Tower — and two connected buildings loom just southwest of downtown, a million-square-foot albatross hanging around the city’s neck, reminding people of Studebaker’s demise. It was never torn down because the city couldn’t afford the cost. But Smith saw the building for what it could be. His vision has precedent elsewhere — in River North warehouses in Chicago and in former tobacco plants in Durham, North Carolina, both now booming tech incubators.

“It’s what has been holding us down as a community,” Smith says. “How fun would it be to take this negative icon and transform it into this 21st century positive icon, to take a building that once moved us a century forward and see if it can take us another century forward?”

What makes Smith’s plans more than idle dreams is his track record. His father, Earl Smith, started Deluxe Sheet Metal in his garage in 1971, bringing in the 15-year-old Kevin to help make gutters and roofing materials.

In 1979, Earl Smith bought the freight area of Union Station for the family business. Two years later, Kevin, who had studied psychology at Notre Dame, purchased the passenger side of the station out of bankruptcy for $28,000 to house his first tech company, a software developer for the construction industry. The 86-year-old Art Deco structure sits across the railroad tracks from Ivy Tower and across the street from South Bend’s minor league baseball stadium. It had once been a major transportation link where three railroads came together, but it was abandoned after passenger train service stopped in the late 1970s. There wasn’t even a key for the unsecured building, which had become a hangout for local gangs.

The younger Smith followed his passion for architecture in restoring the station’s Grand Hall. By 1983, it was being used for formal events from proms to wedding receptions. Four years later, Rochester Communications approached Smith about placing equipment in Union Station. The telecom company was using a string of transponders to push microwave signals along the railroad easement, and it needed to boost the signal power. Smith designed and built the space and utilities to fit their needs and learned plenty about the business. His company’s ductwork experience helped advance the region’s burgeoning tech sector by engineering a patented system to draw off and recycle the excess heat created by high-tech machines.

“I bought Union Station for the family company and because I loved the building,” Smith says. “There was some serendipity that it had access to this right-of-way” just as telecom companies were laying lines and, later, fiber-optic cables along the easements. So Smith developed the abandoned depot into the modern equivalent of a telephone switchboard, where signals are received, intermixed and reconnected. Today Union Station is Indiana’s second-largest carrier hotel, a data center whose customers, including Notre Dame, pay for network and server space and interconnection.

By 2001, more than 20 telecom companies held long-term leases in Union Station. Then the dot-com bubble burst. Smith saw an opportunity. He offered to trade his tenants’ lease liability for an asset they now undervalued — dark fiber.

When fiber-optic lines are laid, the largest cost is digging the trenches, not the wiring itself, so telecom companies often install hundreds of strands and only “light up” what they need. The rest is dark fiber, and Smith collected miles and miles of it. Two years later, the first of about two dozen enterprise companies moved into the station, looking for a place with cheap power and fast connections, no longer restricted by location in an economy of remote computing.

Government and economic development leaders in South Bend, Mishawaka and St. Joseph County had earlier formed a nonprofit called Project Future to promote regional planning. They discovered that a lack of linking infrastructure — the costly last mile of connectivity from an organization’s building to an Internet trunk line — was holding small cities back. So Project Future, funded by seven large data users, including Notre Dame, created a fiber network — more than 50 miles of it — through public traffic signal conduits. Opened in 2004, the Metronet features unlimited bandwidth, speeds 6,000 times faster than a powerful T-1 Internet connection and lower prices derived through the competition of carriers housed at its Internet exchange point — Smith’s Union Station. The Metronet now has nearly 200 local nonprofit and corporate customers.

“The Metronet gave you an opportunity to pick your [telecom] services,” says Pat McMahon ’72, ’75M.S., who led Project Future for 30 years before becoming Notre Dame’s director of technology commercialization in 2012. “By addressing this, we leveled the playing field with any big city, allowing this area to be price-competitive for any data-centric business. That’s a big deal.”

Another big deal: Smith’s business had been growing at 40 percent a year. Union Station was nearly full in 2011 when his gaze strayed across the tracks to Ivy Tower, Studebaker’s old assembly building.

###

Back when Studebaker employed as many as 26,000 people, the Assembly Building could pump out a car body every 12 seconds. The firm stopped making wagons in the 1920s and moved its car-making operations from Detroit to South Bend. The Assembly Building, erected in 1923 from concrete thick as a bomb bunker, took in materials from train cars unloaded on the first floor. Automobile bodies were assembled on conveyer belts and elevators zig-zagging up through the building, ending with upholstery installation on the sixth floor. Huge windows admitted natural light to cavernous spaces interrupted only by sturdy pillars. It was in this period that Studebaker hired Knute Rockne, Class of 1914, as a spokesman and motivational speaker.

By 1950, nearing its 100-year anniversary, the company churned out a high of 400,000 cars and trucks yearly. It finally folded in 1963, mainly because Detroit companies had the scale to sell at a discount and absorb losses.

What Smith found in the Assembly Building nearly 50 years later was a solid shell in disrepair. Ivy Tower had become a rusting warehouse for car bodies, boats and piles of junk ranging from thousands of 1,800-pound diesel engines to boxes of that ancient computer paper with the edge-feeder holes. The building needed hundreds of new windows, environmental remediation and a major makeover. Smith made the city a proposition: Rather than spend up to $10 million to tear it down, use that money instead to renovate it. He promised to invest at least an equal amount to create more space for companies like those in Union Station.

“I said, ‘Let’s take the Studebaker foundation and not discard it but repurpose it,’” Smith related during a 2013 tour of his newly acquired building. “I can bring the core of the new economy and plant it and let it grow in this big building. How often are you given an opportunity — and a responsibility — to give your community another chance?”

Acquiring the building had taken longer than expected. The city finally announced the deal on Dec. 20, 2013, on the 50th anniversary of the shutdown of the assembly line. Twenty spotlights shining into the sky around the city highlighted innovative success stories developed since Studebaker closed, with the last spotlight illuminating Ivy Tower. Smith unveiled ambitious plans that include data centers, enterprise business space, first-floor retail, a glass-topped courtyard, top-floor condos with green-roof patios overlooking the minor league baseball field, and an innovation center that would retrain workers for the new economy. He promised space to the Studebaker Drivers Club and a group of civic-improvement entrepreneurs, recently graduated from Notre Dame, called enFocus.

The design renderings for the Assembly building and its two smaller neighbors that Smith now calls the Renaissance District are inspirational. They may also be unrealistic. Some question whether enough tech companies will want to pay for space half a mile from downtown in an old building between the county jail and noisy train tracks. More to the point, will they pay enough to make the expensive retrofit profitable?

Smith believes his success at Union Station shows they will. He plans to again harness heat from the computer servers to reduce utility costs, and he has committed to move Deluxe Sheet Metal and his other businesses in as anchor tenants.

“You have to be a patient visionary in a place like South Bend,” he says. “This could take 10 to 20 years to unfold. But I’m already getting approached by people who need lots of space, so who knows?”

Remediation work has plodded along, but asbestos and PCB removal were completed in 2014, and lead paint was nearly all stripped by March. Smith expects to have tenants by Christmas. At the very least, he says, the 10 companies he owns could use nearly half the space, about 400,000 square feet, within five years. That would help settle those who worry the project could fail and become a black eye on the city’s comeback story. Many are taking a wait-and-see approach, but city officials say turning a fallen cultural landmark back into an economically viable space will help the community in the long run. “Given the scale of the space, it’s a longer-term expectation,” Scott Ford says.

###

Plans for the rest of the former Studebaker campus south of Ivy Tower are moving forward rapidly. The rebirth began across town in 2007, when Notre Dame announced the creation of Innovation Park, a business incubator to transform University innovation into market-ready ventures. That building opened just across Edison Road from campus two years later, filled rapidly and now nurtures dozens of startups ranging from the makers of superbug antibiotics and nanotech powders to 3D printing innovations and a virtual fitting room. A year after Innovation Park opened, South Bend launched its sister, Ignition Park, on the Studebaker land with the hope of enticing spinoffs from Notre Dame’s growing commercialization enterprise.

Using a combination of local, state and federal resources, the city spent about $30 million to acquire the land, demolish most of the buildings and clean up what they couldn’t destroy, plus another $2.5 million for new roads and utility infrastructure. Some taxpayer advocates objected, but city officials plowed ahead. Their faith began to pay off in 2011. Data Realty, the data storage firm started in Innovation Park, built a $15-million facility in Ignition Park and recently announced plans for an expansion. Notre Dame is both an investor and a customer.

“With improved connectivity, more things are going to cloud-based applications and businesses can be located anywhere,” says Carlton, Data Realty’s president. “I look at the next five years at Ignition Park, and I think we’re going to be surrounded by thriving technology companies and thought leadership that will impact the communities of South Bend and Notre Dame in some significant ways.”

Call Brad Toothaker another believer investing in that vision. The commercial developer and managing partner of Great Lakes Capital is building the two Ignition Park buildings that will house Notre Dame’s turbine testing facility and other high-tech companies. Toothaker began without committed tenants but now has agreements with startups like F Cubed and plans to open the buildings this summer. Future plans call for eight buildings and half-a-million square feet of research and development space, with common areas where creative types can mingle and generate ideas. The company also renovated two prominent downtown buildings that are now home to its own offices, Café Navarre and the software startup Vennli, launched by Gary Gigot ’72, the benefactor behind Notre Dame’s Gigot Center for Entrepreneurship.

Toothaker sees the range of projects stretching from Eddy Street Commons to Ignition Park as more complementary than competitive, building momentum when they succeed financially. He thinks the city is rising “like a phoenix” from the Studebaker ashes.

“A vibrant urban core is the biggest barometer of how you see a community,” he says. “You have to create a certain magnitude. And Ignition Park is turning out to be what was intended — the next stage of life for research coming out of the University. It’s happening quicker than I thought.”

Truthfully, Notre Dame got into research parks late in the game. Stanford University’s parks helped spawn Silicon Valley, and Purdue University now has four parks across Indiana that house 200 companies. But ND has recently increased its commitment, investing heavily in the Office of Research since appointing Robert Bernhard as a new vice president in 2007.

“Like Purdue in West Lafayette, we can create an ecosystem of entrepreneurs here, with some having the potential to grow into major operations,” Bernhard says.

Notre Dame research funding increased from $73 million in fiscal 2005 to $182 million in fiscal 2014, according to data from the Association of University Technology Managers. Today more people and protocols on campus are available to help researchers at every step: to apply for grants and patents, develop an idea and launch a business at Innovation Park; to find investors through a group called Irish Angels; and to grow a company to maturity at Ignition Park.

Buttigieg says a city boasting a world-class research university is “more valuable than an oil well for making it in the knowledge economy that’s on the rise.” As leaner companies and tax-wary governments made cutbacks, universities have increasingly filled the void in research and development.

“‘Commercialization’ used to be a bad word around here,” says David Brenner ’73, the executive director of Innovation Park. “But recently, we’ve come to see it as a way to fulfill our mission to be a source of good, to bring our research to the world.”

It was that kind of institutional support that convinced Gary Gigot to move his family and start a marketing software company in South Bend rather than Seattle, where he’d built a successful career at tech powerhouses such as Visio and Microsoft. He founded Vennli in 2013 with Joe Urbany, a marketing professor in the Mendoza College of Business. He says he found in South Bend everything the business needed: top-quality lawyers and accountants, capital from several sources, talented local employees and professional expertise.

“At 64, you don’t start a software company and move across the country if you don’t have belief in the potential,” Gigot says. “I think South Bend can go far down the path of transforming itself, but it takes companies that are successful to get the flywheel turning. Then you need a whole ecosystem of companies to fill in the gaps, not just one that can move away.”

###

A look at South Bend’s history reveals a sometimes forgotten record of economic greatness. In the late 1800s, cheap power from a dam on the St. Joseph River and mills on the East Race helped sustain 140 factories and the country’s largest companies in three key industries — transportation, farming and clothing. Besides Studebaker’s wagons and buggies, which were used by U.S. presidents and militaries across the world, the inventor James Oliver created an improved plow design with hardened steel to cut through the difficult Great Plains dirt. Oliver Plow converted to mechanized farm equipment before being absorbed in a series of mergers after 1933. Meanwhile, the Singer Sewing Machine Co. produced cabinets at a South Bend plant that employed 3,000 people when the company captured three-fourths of the world market in 1914. Post-war production dwindled after consumer tastes shifted to store-bought clothes.

South Bend’s industrial golden age carried it through the tough times of the Depression. Vincent Bendix, a groundbreaker in the auto and aviation industries, started a company in 1924 that employed more workers in the area than Studebaker. A college education wasn’t needed for a good job. Manufacturing grew to more than half the city’s employment, so the slow ebb at Bendix and the sudden stop at Studebaker hit hard by the 1970s.

It’s often reported that South Bend lost a third of its population in the following decades, but local historians tell a different story. Many people moved to Granger at a time of suburban flight, staying in the county but putting distance between their families and the city’s problems, and unemployment actually stabilized within two years of Studebaker’s closure. The worst sting from Studebaker’s demise was psychological.

Mayor Buttigieg says a part of his job is to convince people that a company like Studebaker is not coming back — and that’s fine. “Frankly, I’d rather have people working 200 at a time at a hundred companies, so that if some come and go, we can absorb that,” he says. “I think South Bend is getting its groove back. You can just feel that people believe in the city again, and that’s contagious.”

Major challenges loom as the city celebrates its 150th anniversary this year, but Buttigieg says the city’s defining quality has been “taking what we have and fashioning it into something new.” Ignition Park and Ivy Tower are part of a tradition, he says, that includes the East Race. Filled with debris for years, the waterway that once powered South Bend factories was transformed into North America’s first urban man-made kayak course in the 1980s. The East Race now draws thousands of tourists a year.

Buttigieg often carries an antique pocket watch to make his point. He explains that the 1909 beauty was made by South Bend Watch and features the city’s name on its face “because the name South Bend was a byword for workmanship and excellence” — a brand powerful enough to sell products. The company folded by 1930 because “they persisted in making the best pocket watches of the early wristwatch era.” They didn’t adapt. But they didn’t need to start making iPods, he says. They just needed to evolve with what they had. “That’s innovation, South Bend style.”

Brendan O’Shaughnessy, who works in communications for Notre Dame, is a former teacher and Indianapolis Star reporter.