The best class I ever had in college was a great class for small reasons, such as there were lots of girls in it, and it was late in the afternoon, and there were fewer than 20 students, and there were no blowhards or suck-ups or preeners or buffoons or conversation-dominators. It was in a cool mullion-windowed hall built of bronze stone, and a most amazing dogwood tree outside the window seemed to miraculously bloom 20 times that semester, so the enticing aroma of dogwood was always drifting into and eddying around the classroom. Dogwood is a lovely smell, evocative of vernal matters like baseball and lawns and holding hands and having your picture taken with your grandmother under a dogwood tree after your First Communion.

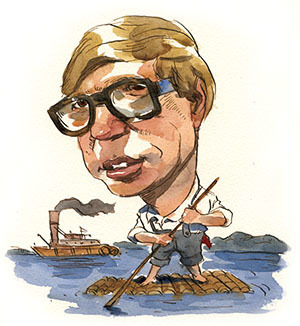

Also there were no exams in that class, as the teacher considered testing your knowledge silly, considering that what he wanted was essentially to get you to bloom as a person interested in and conversant with American stories, using the writings of Samuel Langhorne Clemens as fodder and spark. Also there was no homework other than writing papers on selected aspects of Twain’s writings, or any other writings sparked or influenced by that most unusual man. You could even, if you wanted, write your own essays, as long as they were in some way associated with Twain and his ideas and craft and humor and verve and concerns and adventures; this I did, of course, being even then fascinated by how essays sprinted off on their own once you allowed them their dreamy heads.

I have thought about this class for more than 30 years now, which is an amazing thing to say. While anyone who went to college can remember bits and flashes of particular classes, it seems rare to me that you would continue to contemplate a class, year after year, for more than half your life. But that class seems rather a zen koan to me, something you can consider endlessly and always find new angles and depths and epiphanies in it. This morning, while thinking about it yet again, I realized one of the secrets of the class was that the teacher, bless his soul, wanted us to think not about why, but what.

So much of my education in literature to that point had been about why — why the writer did such and such, why the story was built that way, why the story mattered so then and still. But this teacher gently pointed us back toward the what: What was before our eyes? What was the point and tone and energy of the tale? What music did it set going in ourselves? What did it do? It was easy enough to pick apart the craft of the thing, to identify the tools that had been wielded by a brilliant man from Missouri in service to laughter and fury and rage and reverence, but the deeper education was about how his work stimulated something in his readers.

Not all of them, of course; some students in that class were not jazzed and moved and startled by Twain, and millions of other readers might find him mildly amusing at best. But for most of us, and certainly and unforgettably for me, I was edged over a line — a shadow-line, as Joseph Conrad called it — that I have marked clean and clear ever since. The writing that matters most to me, and the writing I think matters most of all, is that which connects to and startles and moves the reader. I respect news and opinion and persuasion and edification; I smile at rant and roar, dark twins I sometimes commit myself; I dismiss lecture and command and pronouncement, for these things seem arrogant and pompous and incipiently bloody to me; but I love writing that is about the reader, that takes up residence in the country of her heart, that speaks to his innermost self, writing that hits home, that shivers and rattles and rivets the reader.

Such writing can be hilarious and silly, for it reminds the reader that laughter is holy and nutritious and peaceful, a kind of light that we need to survive, just as we need water. Such writing can be furious, for sometimes sharp words and sentences are the only darts that can slip through the armor of lies and fatuousness. Such writing can be abashed and embarrassed, for sometimes admitting your sins and stupidity is the only way readers will be moved to similarly admit their own stumbles. Such writing can use any subject whatsoever to talk about the only subjects that matter, in the end: grace, courage, love.

That teacher’s name was Thomas Werge. We called him Tom from the first moments of that class until the last. The last moments were funny and sad. He gave us back our final papers and shook our hands, and some of the girls hugged him. He was smiling, but I remember two of the girls were crying. The whole room smelled of dogwood again. How a tree can bloom again and again over the course of a semester is a mystery to me, but it seems to me it did bloom again and again, rather like that class, long ago, in spring, in a hall made of stone.

Brian Doyle is the editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland and the author most recently of the novel Martin Marten (St. Martin’s Press).