Midsummer, I was standing in the shade of a tree outside Port-au-Prince’s international airport with a cluster of Americans, helping to load our hired van. The scene outside the airport was calm, nothing like the chaos of my only other arrival in Haiti, five years earlier in the terrible weeks after the 2010 earthquake.

The relative tranquility of the moment allowed me to ask myself a familiar question that would haunt me over the five days of my visit: What am I doing here?

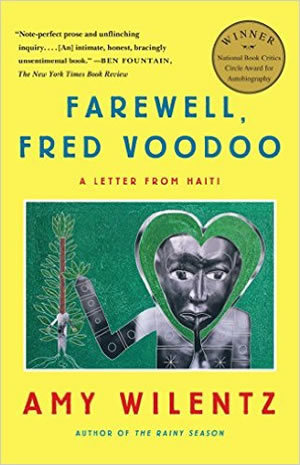

I’ll be the first to say I know nothing about Haiti — or about solar energy’s future there, the subjects of a story I’m trying to write for our winter issue. I’m also wary of parachute journalism, the practice of dropping a writer into a story without prior expertise. Columbia Journalism Review assures me parachuting is okay, as long as my own ruck is “packed with research.” So I picked up Farewell, Fred Voodoo, journalist Amy Wilentz’s 2013 “letter from Haiti,” which I took to be my best bet for getting to know this extraordinary country a little better in 310 pages or less.

I wasn’t disappointed. All parachute journalists have to start somewhere if they’re going to pivot toward authority, and Wilentz was there in 1986, when Jean Claude Duvalier, “Baby Doc,” fled the country and effectively ended 30 years of a brutal despotism handed down to him by his father, Francois, in 1971. Wilentz pitched the decline-and-fall story to Time, boarded a flight from JFK and found a Haitian guide named Milfort Bruno, who “realized quickly that I would interview anyone who had anything to say.”

With Duvalier in exile, she discovered, “everyone had something to say. The whole country had burst out talking (they haven’t really stopped since).” So Wilentz talked to everyone, from the tenuous new occupants of the presidential palace to the residents of the capital city’s most dangerous slums, as well as to the foreign nationals who have always been around and who continue to see in Haiti either a receptacle for well-intentioned charity or a land fertile with opportunity.

In Wilentz’s early days, veteran Haiti correspondents, mostly British, respected her reporting talents but chided her sources. “Ah,” one would say, “you’ve been interviewing Fred Voodoo,” the Haitian person on the street rendered in the now-unfashionable slur of the time. “[T]hat’s what I had been doing,” agrees Wilentz. “Fred Voodoo always had a lot to say.”

Over the next 27 years, Wilentz traveled to Haiti more than 30 times, once to live there for two years, bringing to her work for Time, The New Yorker, The Nation and other outlets a distinctive respect for her sources and the culture, history and politics of their country. All of which meant that when the earthquake struck, Wilentz’s reporting dove to a level far deeper than most American journalists could go. Her forays into the desperate camps and overcrowded hospitals, her analysis of what went wrong with the international relief effort, are richer for the years she’d spent walking the city, observing the customs of religion, food and commerce, watching children grow up and a string of would-be political leaders flare up and burn out. The result is a portrait that replaces caricature with character and assumptions with genuine, human story.

The same question that nagged me during my first and second visits tugs at Wilentz as well, even after all her trips. She questions the Bill Clintons and Kim Kardashians, who in her estimation got some big things out of Haiti while contributing relatively little in return. Sean Penn comes off well in Wilentz’s account, as does an extraordinary American doctor named Megan Coffee, who cooks spaghetti for her starving patients so their tuberculosis treatments might have a prayer of saving their lives. Journalist Mac McClelland, whose essay about her earthquake-reporting experience, “I’m Gonna Need You to Fight Me on This: How Violent Sex Helped Ease My PTSD,” does not.

But Farewell, Fred Voodoo examines the author’s own motives as much as those of others. In this, the book consciously echoes Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, James Agee’s 1941 classic but tortured study of Depression-era poverty through the lens of eight weeks in Alabama’s cotton fields. Agee suffered bitter pangs of conscience during his failed effort to turn his reporting into a story for Fortune; his anguished book contemplates the ethics of the journalistic enterprise in circumstances of gross inequity.

Wilentz’s self-criticism is similarly probing, but her conscience is clearer. She may not be a doer or a helper like Penn or Coffee; she’s “an observer, or (on a bad day) a leech.”

If that’s the case, then Wilentz is a profoundly better informed observer-leech than the likes of so many others like me. Farewell, Fred Voodoo is about discarding stereotypes and engaging something real that disturbs us without indulging in the impulses to impose, to exploit, or to “fix” — if by fixing what we really mean is making something more like us and like ours. Essential things to keep in mind, the next time I pack up my parachute.

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine.