I was lounging in a bathtub when the police called. Despite the messy relationship between flip-phones and water, I managed to answer.

“Would you like to come down to the barracks?” the state trooper asked.

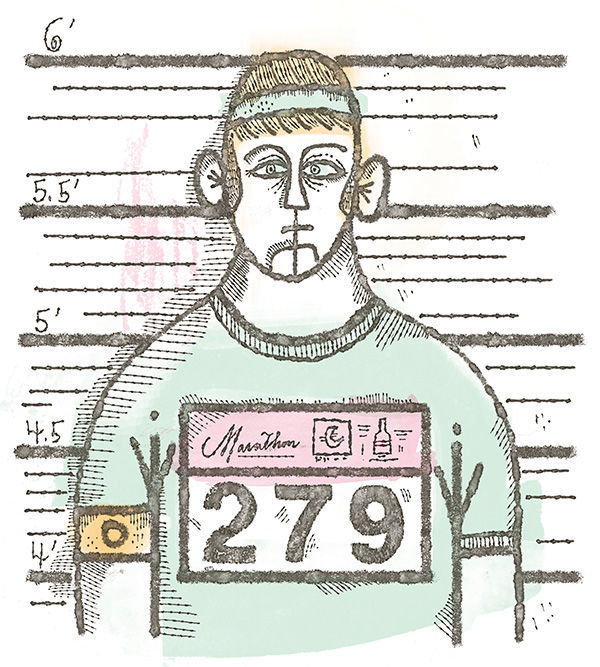

You don’t hide from the police, especially if you have something to hide. Good liars don’t feel the tremors, the sweat, the Sherman McCoy panic, the overall social ineptitude that plague me in these situations. That evening, as the trooper led me downstairs to the interrogation room, I struggled even to walk. I could go to jail. They say the steep downhill stages deep into a marathon burn your quads to ash. Descending those stairs felt like my 26th mile. Almost to the inch, it was.

Past the transparent bulletproof barrier that separates Pennsylvania’s finest from their waiting room, overflowing folders sat atop office furniture scattered amid a finished basement. The surroundings befit the alleged crime — ragtag but mysteriously so. The officer sat down at his desk calmly. This was a summit, not an ambush. “Why don’t you just tell me your story?”

“Sir,” I started, averting my eyes, as I do when toiling to formulate sentences, “I was running a marathon.” He did not do a double-take, nor narrow his gaze, nor ask the obvious: “What, here? Out there?”

It was early in January. The exact day, one circled in my planner for so long, somehow escapes my memory now. Little else does. The snow we’d received so far that winter had melted; Chester County’s mushroom farms and manicured lawns oscillate each winter between Christmas-card scenes and amber grass. The mere mention of snow would have repelled any real marathon organizer. I’d seen the other end of the spectrum. During the previous summer, my friend trained for the Chicago Marathon — the 2007 edition, the infamous 88-degree meltdown that was canceled midrace — and inspired me, in a one-upmanship sort of way, to try a marathon myself. I was an unaccomplished runner. I had never done more than five miles. But Google gave me a 16-week regimen for beginners, and my day arrived.

“Sir,” I told him, “no one knew I was running a marathon. You’re the first to know.” What a statement, yet he still betrayed no suspicion. I wanted to prove to myself that I could run it, of course. All first-timers want that. But I wanted more. Above all I yearned to have the humility not to brag about my feat. Do not announce it with trumpets as the hypocrites do. They have already received their reward. I wouldn’t tell a soul. I hadn’t throughout my training.

This clearly ruled out a major organized race. That would draw attention. Ticker tape, NBC10 crews, water stations. Energy packs. Fans lining the streets. Support. My marathon lacked all these. So on a map around my house I plotted 26.2 miles, notes in an ode to suburban Philadelphia and a hymn to self-reliance. At the finish line lived my boyhood love and close friend, whom I’d asked to drive me home, though she did not know why. The rolling hills would wind me through my upbringing, past heartbreaks on Little League diamonds and rejections at dances and first jobs and football glories and school recess courtyards, and atop the final climb I would fall to my knees, kiss Chester County and know that I could do anything.

“There’s my itinerary, officer,” I said, handing him a receipt-sized list of back roads. Ink ran; the paper spent the marathon in my pocket. Right Baltimore Pike, where Washington and Jefferson, the stories went, rode past the Red Rose Inn. Right 896. That was seven miles uphill straight into 30-mile-per-hour northwesterlies. Saliva froze on my cheeks.

Left Flint Hill Road. I trained during the semester in the slush at Notre Dame. Midwestern hills are speedbumps. Heartbreak Hill in Boston, known for ending the dreams of many marathoners, climbs 91 feet. Flint Hill, my marathon’s toughest, climbs 263 feet. The average grade: 5.4 percent. It’s almost twice as steep.

Right 841. This was to be my Champs-Élysées, three miles of a triumphant march into the finish. But I was sputtering, bobbing, jogging slower than I normally could walk. When would this incline relent? Why must there be another after it? You wanted to do this yourself, and that means you don’t have anyone handing you water or food. Not even Olympians do that.

At some moment on 841 I didn’t care — though I knew I would immensely later — that I could throw away four months’ preparation by stopping. I might have had more energy left. Maybe the cold and the terrain defeated me. I don’t think so, though. I searched for humility, and it was pride that defeated me. I crawled to a walk. It is one of the grandest failures of my life. Being incapable could be forgiven, but quitting could not. I had wanted to say I could do anything I worked toward. I was wrong because I would surrender. I had no discipline. I was a waste, a waste who had eschewed others’ help.

Now I desperately needed it. The finish at Sarah’s house sat two miles away. My legs were crippled by three-and-a-half hours outside, 25 degrees and falling. It would be dark in an hour. No cars were passing by. Sweaty clothes — my unraveling 1993 Phillies sweatshirt and Notre Dame shorts. I knocked on every door I found, a new one every eighth of a mile. No one is home at 4 on a weekday afternoon. I’m going to freeze alive out here. And soon I won’t even be able to walk.

“You didn’t bring your cell phone,” the trooper said. “She’d have picked you up in five minutes.”

“That would have been preparing for failure.”

Another house — this one with a driveway steeper than Flint Hill. An open garage! “That meant someone would definitely be home,” I told him. Knock. I called out for help. Nothing. I entered the garage. The door to the inside was closed. My numb hand could not feel it. Just get to a phone. Locked.

“The girl said you tried to break in.”

“I rattled the doorknob.”

There, on the garage floor. How to transport the bike back in Sarah’s Civic? How to pedal the bike? I wasn’t thinking. It was survival mode. I’d bring it back right away. I took it and breezed down the driveway and could see myself warming up in no time. Then I tried to pedal.

My legs were useless. I couldn’t propel the bike 10 feet forward. Couldn’t carry it back up that mountainous driveway. Off to the side of 841 South it went. Panicking, fighting to stay upright with every step, I searched for another house.

Instead, a minivan! It stopped, and a woman my mother’s age lowered the window. “Please, can you help me? Can I use your phone?”

“Is that your bike on the road?” she asked.

“No, it’s not.”

“Did you take it from —”

“I was trying to get —”

She was already raising the window. “I’m sorry I can’t help you,” she said frantically and sped off.

Finally, another quarter-mile later, an elderly couple took me in and let me call Sarah, who drove me home. On the way I saw the policeman at the open garage. Now we were sitting in the barracks.

“Well, I want you to know I believe you,” he said. “I’ll talk to the family in that house and see if they won’t press charges.”

A few hours passed, waiting for arrest or absolution. That night, the flip-phone rang again. They did not wish to press charges and ruin a college kid’s life. So I picked up an apple pie from Acme and thanked the elderly Good Samaritans for saving me from frostbite. Then I stopped at the other family’s home. I knocked, and this time the door opened.

“My daughter was home earlier,” the mother said. She couldn’t have been more welcoming. She showed me pictures; her daughter was pretty. “She even recognized you from church.”

“Why didn’t she answer?”

“I was the driver in that car. She called, and I came straight home. You looked like a crazed drug addict. You were foaming at the mouth.”

I could only laugh. “I’d just run 24 miles, I guess.”

She thought a second more about that encounter. “You always hear about people who won’t help others,” she said. “You think of the stories when a Good Samaritan tries to help and it backfires, some killer tricks them. You just never know who’s out there now.” She was tearing up. “I always said I wouldn’t be that person. I’d never turn someone away. And then today you were there. I’m so sorry.”

Michael Augsberger’s essay won first place in this magazine’s 2015 Young Alumni Essay Contest. The author still lives near Philadelphia and is an aspiring financial adviser at J.P. Morgan. He coaches tennis at his high school alma mater, Salesianum. He can be reached at michael.augsberger@gmail.com and his work can be read at maugsberger.blogspot.com.