The Holy Father’s recent visit to America brought back some warm memories from my very Catholic childhood, when the pope was something of a hero in our house. Not only had Paul VI made the post-Vatican II folk Mass in the St. Vincent’s gym possible, he also validated sprawling families like ours (14 kids) when he condemned contraception in his Humanae Vitae.

Like many of my boyhood peers, I grew up with an eye on the priesthood, but my interest in girls intervened. After completing 16 years of Catholic school, marrying my high school sweetheart in the same church where I was confirmed and starting the naval service required by my Notre Dame scholarship, I maintained my affection for the pope even as my dutiful submission to his authority waned.

My sense of dissatisfaction started with more abstract things, like pondering the justice behind a theology that consigned the unbaptized to hell and subordinated the female half of our species. Using the intelligence and leadership abilities of my mom, five sisters and wife as a baseline, I concluded the Church was missing out on some real human capital by excluding women from leadership roles.

Despite my growing misgivings, I still found comfort in the Church and the meditative familiarity of the Mass. When deployed on a destroyer in the Red Sea (during the conflict my children are required to describe as “The Great War: Desert Storm I”), I was always glad when a Catholic chaplain helicoptered aboard for a quick blessing and a Mass.

As the years went by and friends and siblings fell from Catholicism onto paths ranging from agnosticism to New Age mysticism, I felt an obligation to stick around and maybe even fix things. After all, I stood near the altar while strumming at the occasional guitar Mass, so why couldn’t I be the one to tackle the Church’s big challenges? In the calculus of my arrogance, I figured the Church was ready for a new hero to emerge from the ranks, namely me. The question was where to apply myself first.

It turns out the answer was at home. Four years after my wedding, my desire to save the Bride of Christ evaporated as my actual bride took a break from a marriage starved by Navy-related absences. Our neatly pressed life had buckled under the weight of my own ego, leaving me alone in a one-bedroom Dallas apartment, adrift in a sea of Baptists and Aggies. I needed help fixing things, and fast.

Since I’d been trained since birth to see priests as conduits of God’s wisdom, I made a token visit to the local parish for guidance but had doubts an unmarried cleric could be much help when it came to marital repair. I was also embarrassed at the prospect of a looming legal proceeding that would be a giant step toward possibly losing my lifetime membership in the Catholic club. So I left before they could fire me.

On consecutive Sunday mornings, I’d driven past a knot of well-dressed people smiling and waving from the curb outside the town’s fine arts facility, which was festooned with a banner advertising a church. They lacked the glassy-eyed stare of the typical cult, so I reached out to one of my brothers, who’d previously “gone evangelical,” for a cult check. Based on his assurances of their legitimacy, I paid a visit the next Sunday. From the comfort of a cushioned theater seat, I looked on in confusion as a rock band warmed up the crowd for a pastor in a fancy suit and shoes that sparkled in the theater lights.

My guilt associated with cheating on Catholicism melted away as this married pastor got rolling, connecting scripture to marriage with personal stories and preaching a “once saved, always saved” version of faith. I was hooked.

In short order, I became a regular attendee and discovered “altar calls” and “praying the prayer.” Most evangelical churches, I learned, preach that faith is a decision, a response to the prompting of the Holy Spirit to accept God’s offer of salvation. That acceptance comes in the form of a heartfelt prayer confessing one’s spiritual frailty, asking forgiveness and accepting Jesus as your personal savior. It’s what many call being “born again.” It’s usually followed with baptism by immersion (think O Brother, Where Art Thou? without as much pretty singing).

While I was meeting new people at church, my parents were 1,000 miles to the north and my wife the same distance to the south. At age 26, I was truly alone for the first time ever, humbled by my own failings. However, in the dark silence surrounding one who has finally hit bottom, I experienced that still, small voice the prophet Elijah heard. I knelt by my bed, feeling the weight of my failure, and decided to pray the prayer. No tongue of flame flickered above my head, but I genuinely experienced the presence of the Holy Spirit and the beginning of a root-level spiritual transformation.

In the following months, I took a headlong dive into the evangelical faith, memorizing Bible verses, learning the Four Spiritual Laws and getting baptized in a rich guy’s swimming pool. I started to see a genuine connection between my everyday life and biblical truth. As the compass needle of my identity began to swing from my ego to my faith, I recovered the confidence to court my wife. In a miracle on par with Jesus feeding the 5,000, she returned to Dallas and eventually started attending church with me.

Like the many seemingly nondenominational churches one sees renting facilities or renovating basketball arenas across the country, the megachurch I joined had a secret: It was actually Southern Baptist. My father, a proud Domer himself, couldn’t accept that fact, even to the day he died. As I sat down for our last conversation, just days before pancreatic cancer finished its nine-month journey to his center, I hoped to hear a “Well done, son. I’m proud of you.” Instead, he rasped, “If you could do one thing, it would be to return to the Church of your father.” I lied when I said I’d think about it, and I hugged him goodbye.

Over the next three years, my faith immersion progressed to the point that I accepted an associate pastor position at a church in Austin, Texas. With nary an hour of seminary training or even a decent cassock, I was ordained by our senior pastor and got to work. For the next seven years, I helped plan services, promoted the church with everything from direct mail and websites to billboards and TV ads, pitched in on a multimillion-dollar building fund campaign and oversaw multiple teaching ministries. I preached when my boss was out of town, wrote Vacation Bible School scripts, married people, buried people and just generally relished the meaningful toil of ministry.

However, I spent those years harboring a dark secret: I was still part papist. Besides sneaking the occasional beer in the privacy of my own home and obsessing over the gridiron exploits of the Fighting Irish, I’d slip into Catholic services on the sly. More than once, I headed downtown to St. Mary’s Cathedral for a moment of reflection when preparations were completed for our own grand Easter and Christmas services.

Having become an architect of high-energy megachurch worship experiences, I found myself craving the moments of familiar stillness available in the cathedral’s wooden pews. Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve and Stations of the Cross on Good Friday were the comforting faith equivalent of home cooking.

After seven years in full-time ministry, I ran out of gas. I was exhausted by the megachurch’s relentless emphasis on growth. (In their defense, they’re driven to “get everyone into the boat” of salvation because hell is hot and heaven is sweet.) I had also realized women were excluded from leadership just as fully as they had been in Catholicism. At the same time, emerging evangelical prophets such as Shane Claiborne were preaching a “new” gospel of compassion for the downtrodden. As a result, my passion for smoke machines, entertaining videos and Foo Fighters covers in church waned. My faith was strong; my religious flame had flickered out.

In 2007, after all those years of finding my identity in ministry, I left my office and the church for the last time. With a wife and three kids on the payroll, I had precious little time to ponder the universe, so I dove into a secular career. Given the similarities between sermons and political speeches, my transition to the political arena — as speechwriter for a certain well-known Texas governor — was fairly smooth.

With a new career underway, the selection of a replacement church was, at best, a halting process. I’d seen the sausage made in church and had little appetite for more organized religion. Instead, I adapted my years of creating church services for an audience of four, leading Sunday morning devotionals with just our family in our living room. To the best of my ability (and by God’s grace) they were Bible-based, full of prayer and occasional moments of genuine compassion between siblings. We’d still visit St. Mary’s on Christmas Eve or check out evangelical churches that popped up in nearby schools, but we spent years focused on our nuclear family church.

- Related story

- Francis on My Mind

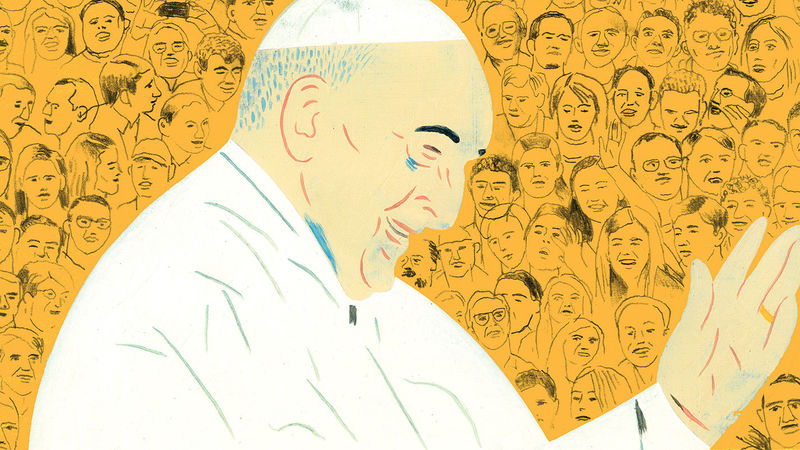

I did notice when Pope Francis took office, but I was more cynical than joyful, wondering when his humble shtick would taper off. However, the drumbeat of unusual pronouncements emanating from Vatican City only grew stronger and more consistent. If I was caught off guard by his humility, his dispensation with the trappings of the office and his insistence on simply touching people, I was eventually won over by his unwavering emphasis on grace, acceptance and love. I sensed a leader pushing the door open for me.

Nowadays, I check Mass schedules at the local parishes and occasionally sneak into a service, where I sit in the back and soak it in. I suspect the parishioners know I’m an interloper because I consistently trip over Benedict’s changes to “the script” — I still don’t get the whole “and with your spirit” thing. It may be my wishful thinking, but there is a general sense that Francis has restored an essential human element to the Catholic experience. I’m not saying the human element ever left, but it was certainly overshadowed by decades of dogma and doctrine that kept the head busy but the heart untouched.

As I see a leader who eschews the Popemobile because it conveys a lack of trust in God’s plan, who washes the feet of the homeless and who would probably show up for work in a soccer jersey instead of a cassock, I feel a shift in my soul. I find my heart tilting back toward a Church whose essential greatness is based on the teachings of a perfect man in an imperfect world, a man who chose to touch lepers, encourage fishermen and challenge the entrenched powers to bring about heart-level change for the very people He knew would watch mute as He was executed.

As the mania surrounding his U.S. visit showed, Pope Francis has caught the attention of expatriates like me. His loving humility is reminding us of what made “the church of our fathers” so great. Refinements to the language of Mass and theological abstractions aside, his simple, Christ-like focus on the preciousness of the person in front of him is redefining Catholicism for me and increasing the odds of my father’s deathbed wish coming true. That counts as real heroism in my book.

Andrew Barlow is a leadership communications consultant living in Austin, Texas.