Kate Smith, the First Lady of Radio, came to South Bend on October 4, 1940, with several Hollywood celebrities to promote the premiere of the movie Knute Rockne, All American. Smith’s hour-long variety show was broadcast coast-to-coast on the CBS radio airwaves from the auditorium of John Adams High School. Fittingly, 40 members of the Notre Dame Glee Club performed several school songs, and the band played the “Victory March.” To close the program, the University’s flagship all-male chorus backed up the incomparable Smith in a special arrangement of her signature song, “God Bless America.”

On the same weekend 75 years later, the Notre Dame Glee Club made history among student organizations at the University. More than 500 alumni returned with their families to celebrate the centenary of the esteemed group, chartered in 1915. (Although reports of Glee Club activity can be found dating back to the late 1800s, a set of unbroken years of operation can be marked from exactly 100 years ago.) The centennial event was the largest reunion of a Notre Dame student organization ever orchestrated on campus. Glee Club alumni from the class of 1942 and onward — traveling from at least 43 states and six countries — returned to South Bend for the chance to gather with classmates and ring out songs still alive in the current repertoire and others nearly forgotten.

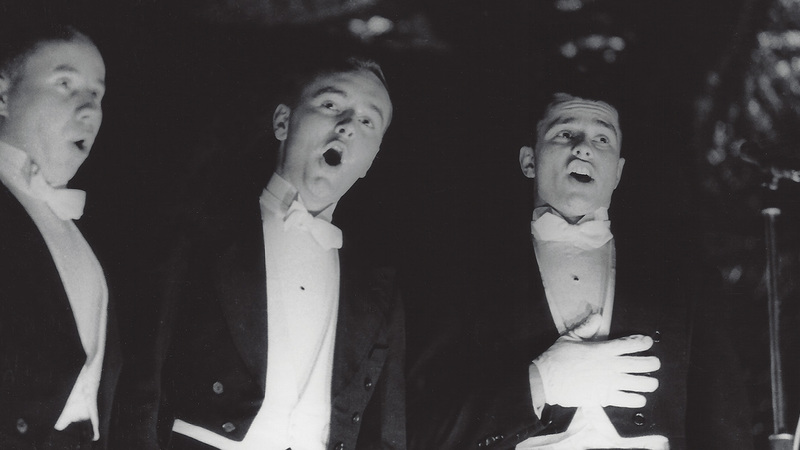

The highlight of the weekend came when the full chorus — 508 alumni and 68 current members — stood shoulder-to-shoulder on the stage of the Morris Performing Arts Center in downtown South Bend on Friday, October 2. No stage or auditorium on Notre Dame’s campus could have held the chorus or the large audience. The gigantic sea of singers performed a set of pieces representing the Glee Club’s musical core, and a generous donation from an anonymous Glee Club alumnus ensured that all returning members could afford to don the traditional white tie and black tails for the evening concert.

Music-making is at the center of a Glee Clubber’s experience, but memories are made not in song alone. The fraternal bonds formed on campus and especially away from it, as well as in the many traditions of the group, inform its collective memory. For decades, the Glee Club has enjoyed global touring opportunities that are rare among collegiate or even professional music ensembles. At the banquet of the centennial reunion, current Glee Club director Daniel Stowe reflected on the extraordinary privilege and dividends of traveling for concerts: “Touring is at the core of what we are as a club. How many of our fondest memories — mine included — took place on Glee Club tours? It’s the fount of our professionalism as a club.”

The group began touring in earnest in 1915, another reason the club’s origins are marked in that year. Following nearby “run-out” concerts in northern Indiana and southern Michigan, the club ventured to the Murat Theater in Indianapolis for a program sponsored by the Notre Dame Alumni Association. That performance drew more than 2,000 spectators, including the governor of Indiana and the mayor and the bishop of Indianapolis. After strong reviews in the press, more tour sponsors beckoned.

In the past 100 years, the group has visited the 48 contiguous states and countries in both hemispheres. Before 1950, domestic tours were concentrated in the Midwest and on the East Coast, but Glee Club travel since that time has been more reflective of the geographic diversity of its membership — and it is not uncommon for the ensemble to stop in the hometowns of individual club members. Since the term of director Douglas Belland (1979-81), members whose hometowns the Glee Club visits are offered the opportunity to conduct the ensemble in the singing of the University’s alma mater, “Notre Dame, Our Mother.”

In 1928, the Yale Glee Club was the first U.S. university chorus to travel overseas. Despite its high-profile domestic travels, Notre Dame’s Glee Club was a latecomer to international trips. The club first toured internationally in 1971, with some assistance from Glee Club alumnus and University trustee Alfred C. Stepan Jr., class of 1931. Concert tours through Europe were conducted every three years from 1975 through ’97, when the scope of club travel expanded to the Middle East with a special invitation to perform with the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra in Israel. Since then, travels have taken the club to Asia and Latin America. A tour to Guatemala in 2009 included 25 members of the Notre Dame Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble Stowe has conducted since 1995. It was the first joint trip — international or domestic — for these two musical organizations from Notre Dame.

Glee Club members made a particularly memorable trip in 2013, when they journeyed on the Camino de Santiago, the storied medieval pilgrimage route that Christians for centuries traversed across northern Spain to the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela. The singers walked an average of 15 miles per day on the Camino, and club president Brian Scully ’13 remembers “talking philosophy, telling stories, playing games to pass the time, or complaining how much our legs hurt.” Most of the concerts on the trip were performed in Galicia, a region in northwest Spain uniquely infused with Celtic cultural heritage. The club’s renditions of two Galician folk songs (“O voso galo” and “Catro vellos mariñeiros”) were met consistently with standing ovations, even in the middle of concerts.

Long-distance hikes are not a usual feature of club tours. In 1927 and ’28, student business manager Andrew Mulreany organized particularly ambitious tours by rail, which included meeting President Coolidge at the White House, and a 6,000-mile tour of the American West and South. After chartered buses became the principal mode of transportation for the Glee Club in the 1950s, Indiana Motor Bus was the club’s preferred carrier for three decades. For nearly a decade (1957-66), a single driver, Dick Aust, transported the club thousands of miles in a vehicle that was sometimes branded with the group’s name on the side.

One of the most poignant domestic Glee Club tour stops was a concert in New York City just five weeks after the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center towers. The concert at St. Peter’s Church in Staten Island, New York, on October 25 raised money for the Twin Towers Fund, a charity benefitting the families of first responders who died on that day. Down the street from the church was a minor league baseball stadium, which had been transformed into a morgue to receive the bodies from Lower Manhattan. The church was set up with broadcast equipment to air the Glee Club’s performance on public radio, and the back doors of the church had to be opened for audience overflow.

At the beginning of the concert, the ensemble was escorted to the front of the church by New York Police Department bagpipers. Chris Clement ’02 recalls that “cheers from the crowd, even before the concert really began, showed their relief at being able to do something ‘normal.’” The first half of the program concluded with Franz Biebl’s stirring “Ave Maria” for two choirs — a signature Glee Club piece — followed by a special presentation of Big Apple lapel pins for the Glee Club members, which they donned for the second half of the performance and for every concert that year.

During the performance, several firefighters in the audience were called away for an emergency. At the end of the evening, a fire truck — a potent symbol of September 11 — pulled up to the church. The firefighters who’d left the concert had returned to thank the Glee Club for its charity.

In the club, fraternity is cultivated on a daily basis, whether dining communally, volunteering for charities or singing informally around the campuses of Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s College. On Friday evenings before home football games, the group sings a short set of school songs while standing on their chairs at South Dining Hall. Arranging formal and informal gatherings throughout the year typically falls on the shoulders of the Glee Club’s vice president, who organizes such events as dances, hayrides, off-campus parties and outings to the Dunes. Some of these occasions bring out an underground repertoire of off-color songs that was never intended for the concert stage.

More than 2,000 young men have sung with the Glee Club, whose size has varied considerably in its 100-year history. The club was composed of around 20 singers during the middle of World War II but ballooned to 150 by the mid-1950s. In the late 1930s, a junior varsity club was created to handle membership overflow and to serve as a training ground for promising young voices.

Among the hundreds of men who were in the Glee Club, it is hard to single out particular singers to spotlight, but it may be noted that two of its members — Charles Butterworth, a 1924 law graduate, and Walter O’Keefe, class of 1921 — have been awarded stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Butterworth stayed in film for his career, while O’Keefe was a songwriter, Broadway star and host of both variety and quiz shows on radio and TV. Two gifted music conductors have emerged from the ranks of the Glee Club: John Oliver ’61, founder and recently retired conductor of the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, and Patrick Dupré Quigley ’00, founder and artistic director of the Grammy-nominated chamber choir Seraphic Fire.

Those individuals who have stepped onto the podium to conduct the Glee Club can be credited with shaping the sound one encounters in performance. The 1915 group was directed by Samuel Ward Perrott, a Harvard law student and 1916 Notre Dame Law School graduate who brought to South Bend the serious repertoire and standards of the Harvard Glee Club. While Perrott’s term lasted only one year, he put the Glee Club on the road and in tuxedos.

Although Joseph Casasanta directed the club from 1926 to ’38, he is widely known to the Notre Dame community for having written some of the University’s most enduring songs. With his brother-in-law and Notre Dame architecture professor Vincent Fagan, Casasanta penned “Hike, Notre Dame” in 1924, which captured the campus-wide fervor around one of Knute Rockne’s new formations on offense. In a span of eight years, he added “Down the Line” and “When Irish Backs Go Marching By” and, finally, the University’s alma mater.

Though less prolific a composer than his predecessor, Daniel “Dean” Pedtke — a nickname he earned as chair of the music department — was an accomplished pianist and organist at the time of his hiring. The club had traveled extensively and became nationally known under Casasanta, but he eventually had lost the good graces of an increasingly conservative University administration, which was concerned about the direction of the group and its characteristically light repertoire of secular, folk and school songs. The soft-spoken Pedtke earned anew the trust of campus officials in short order with a supply of more serious music.

After Pedtke’s very first concert on campus in 1938, Prefect of Discipline Father James Trahey, CSC, promptly wrote to the new director, “I enjoyed every minute of what I heard. . . . There is a finess[e] about this year’s Glee Club which bespeaks cultural background and which has been sadly lacking for a number of years. I believe a glee club can be, and should be, primarily a cultural influence and not just a ‘Rah, Rah Chorus.’”

Under Pedtke (1938-73), the club witnessed a growth of touring opportunities and the height of its national visibility. For seven consecutive Easter Sundays between 1949 and 1955, touring members of the group appeared on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town, the top-rated television show of its time. By this measure, the Notre Dame Glee Club approached household-name status.

When Pedtke suffered a disabling stroke in April 1973 that marked his retirement, the club passed into the hands of 27-year-old organist and composer David Clark Isele.

Despite the ensemble’s command of the national spotlight, questions regarding the club’s programming were brewing in the administration, not unlike those raised in the Casasanta years. Coupled with the 1972 advent of coeducation at Notre Dame, the music department recommended the all-male singing organization be eliminated. The department proposed instead a mixed chorus with loftier repertory standards. Blindsided by this pressure, Isele instituted some changes that quelled the departmental concerns about the amateur men’s chorus, such as re-introducing the Glee Club to madrigals. He also founded a mixed chorus, Notre Dame Chorale, and talk of the all-male group’s viability subsided.

Carl Stam, 28, took the reins of the Glee Club in 1981 on the recommendation of then music department chair, Professor Calvin M. Bower. Stam had been a student of Bower’s at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. The boyish-looking Stam, whose energy never seemed to flag, continued to broaden the repertory horizons of the group — normal for each director — introducing, for instance, the musical challenges presented by early 20th-century composers Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc and Charles Ives. Stam also infused the repertoire with Renaissance choral music and medieval plainchant. Sadly, two decades after he left Notre Dame in 1991 for a career in music ministry, Stam lost a long battle with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A National Marrow Donor Program sponsored on campus in Stam’s name drew hundreds of new registrants.

Since 1993, the Glee Club has been directed by Stowe, who is expanding the club’s international reach. His eclectic taste — in particular, his penchant for Renaissance sacred music, folk songs of the British Isles, concert spirituals and barbershop arrangements —has not only shaped the substance of seven recordings to date and programs of the past two decades but also equipped the ensemble with music for virtually any occasion.

One particularly happy occasion happened in 2004 when Notre Dame opened the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center, which included the 840-seat Leighton Concert Hall. “I’m still amazed anew when I walk into the concert hall that they actually built it,” Stowe says. “It’s a continual motivation to prove ourselves worthy of it.”

Although Notre Dame is better known for football than for music, the football enterprise actually was helped in its infancy by the Glee Club. In 1888, it billed one of its on-campus concerts as a fundraiser to buy uniforms for the still-winless football team.

The Glee Club has been closely tied to the football culture of the University, with concerts before, during and after games. In 1931, 120 members of the club sat together in Notre Dame Stadium to lead the student body in singing the school’s pep songs during a game against the University of Pennsylvania, emulating a similar musical practice inspired by military academies. In 1933 and ’34, the section of Glee Clubbers was located behind the band around the 30-yard line, a move orchestrated by director Casasanta for “the purpose of stimulating organized singing and cheering among the students.” Since the early 1980s, the Glee Club’s pregame “revue” concerts, now held in front of the reflecting pool of the Hesburgh Library on game day, sometimes draw more than a thousand spirited fans.

Like the football team, the Glee Club has its own chaplain, mainly assigned to accompany it on tours. Father Robert “Griff” Griffin, CSC, ’49, ’58M.A, held the Glee Club chaplaincy for more than a generation, traveling thousands of miles each year by bus with the group and celebrating Mass with the young men at many historic places in the United States and Europe.

The club that began in earnest a century ago has risen in status even as the mixed choruses around it flourish. It continues to test both the bounds of evolving artistic standards and the geographic boundaries that once limited Notre Dame’s reputation to the Midwest but now lead to all parts of the globe. In anticipation of the Glee Club’s centenary, Father Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, wrote in 2014, “One of the greatest assets we have here at Notre Dame is our Glee Club. . . . May I say that I am grateful for all of the wonderful performances of the Glee Club, not just here on campus but around the world. I have enjoyed many of their performances each year and I never cease to be edified by their spirit and wonderful presentation.”

In the “Notre Dame Day” fundraiser last April, alumni and students were encouraged to nominate their favorite student organization or entity on campus, and the nominees in turn would receive a proportionate share of the dollars raised. The Notre Dame Glee Club was the hands-down winner of the contest, topping even the football team.

Michael Anderson, a member of the Notre Dame Glee Club from 1993 to ’97, is an associate professor of musicology at Eastman School of Music, Rochester, New York, and the author of The Singing Irish: A History of the Notre Dame Glee Club.