A packed hall at Oxford Divinity School is waiting for the first lecture by an editor from the London office of Oxford University Press. Right on time, the door opens and three figures walk in. Two of the men are among the most beloved writers of the 20th century, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Between them is a strange-looking bespectacled man. As he begins to speak, the listeners fall under his spell. By all accounts, everyone present was in awe of his insight, his brilliance and his raw charisma.

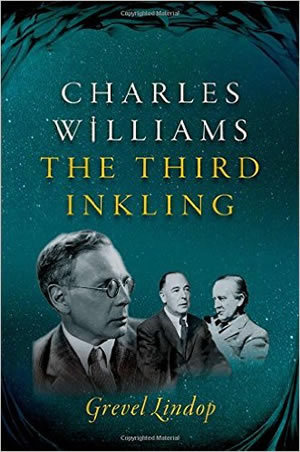

This story from the opening pages of Grevel Lindop’s Charles Williams: The Third Inkling reveals a startling but puzzling truth. Charles Williams, in spite of being called “One of the most gifted and intellectual Christian writers England has produced this [the 20th] century” by Time magazine, has always walked in the shadow of his two famous friends. Everything he wrote, did or said has been analyzed by and through his relationship to The Inklings and its more famous members, Lewis and Tolkien. Even in last year’s excellent literary biography The Fellowship, Williams is given a secondary role in the legendary writers group.

Lindop seeks to correct that perception and show us the genius of the man many have referred to as “The Magician.” He does so by asking two questions. First, why has Williams not enjoyed the near saint-like status bestowed on Lewis and Tolkien despite writing profound theological works? Second, how should Williams’ work be understood not only in light of the Inklings but in the larger literary world?

Williams was a complex, strange and sometimes disturbing person. While Tolkien lived the life of a near saint, and Lewis seemingly beat his demons upon his conversion to Christianity, Williams struggled with his dark side his entire life. Lindop shares discomforting letters Williams wrote to young women that show a “master/apprentice” relationship which would often involve real spankings for supposed infractions. He carried on a passionate but unconsummated (despite her strong desires to do so) love affair with Phyllis Jones, a librarian at the Oxford University Press London office. Finally, he was a part of a mystical Christian group that practiced magical ritual while refusing to seek magical powers. Not exactly a man who can be marketed to the polite suburban Protestant church crowd. However, Lindop also demonstrates that Williams’ struggles with his dark side helped him to wrestle with some of the more difficult questions of Christian thought: what to do with human sexuality; the problem of suffering; and the transformative capabilities of the light of Christ, whom Williams called “The Messias.”

In addition to proving Williams’ worth among the Inklings, Lindop seeks so establish him as a major literary figure. While much of the previous Williams’ scholarship focused on his six paranormal thrillers or theological works, few scholars have discussed Williams’ driving passion, his poetry. He wrote in the style of his friends, T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden, poets who invited multiple readings and further reflection. In his poetry, Lindop argues, we see the inner struggle of Williams, battling his dark side with his firm belief in the Messias.

In the tension of his poetry, we also see Williams’ greatest strength: his ability to see all sides of an issue. Lindop shows how he brought this ability to the Inklings and provided a spark that fired the imagination of the greatest writers group of the 20th century. Indeed, as Warne Lewis (brother of C.S. Lewis) wrote, the group was never the same after Charles’ death.

Lindop argues that Williams’ influence was and is not limited to the Inklings prominent writers. Eliot, Auden and others have written about the influence of the strange editor from Oxford University Press. Catholic novelist Tim Powers talks about the deep influence of Williams on his own work. Protestant theologians J.I. Packer and Eugene Peterson have raved about Williams’ theology and its mark on their own understanding of Christian doctrine.

Personally, I’ve felt the power of his influence through his stories, theology and way of thinking, which creeps into my own published novels. My acknowledgement of his influence led to my editor at Open Road Media asking me to write an introduction to the rerelease of Williams’ novel War in Heaven, probably the highlight of my own writing career.

This wide variety of influence supports Lindop’s belief that Williams deserves to walk side by side with Tolkien and Lewis as one of the best Christian writers of the 20th century. And I personally hope Lindop’s well-written biography will introduce a new generation to the work of The Magician.

Jonathan Ryan is an editor at Ave Maria Press and the author of 3 Gates of the

Dead.