Faint buzzing and humming noises fill Room 115 in Crowley Hall of Music, as two students warm their voices. They shift into their respective places near a chalkboard encircled by a few chairs. A pianist tunes in the back corner.

“Let’s start on measure 160,” says stage director Leland Kimball, former general director of OperaDelaware.

The pianist sets his fingers to the keys, cuing a student holding a broom in his hand.

“He keeps me here at home unkempt . . . His horses are bred better . . . I will no longer endure it,” the student sings.

“Don’t lay your hands on me, you villain . . . Let me go, I say,” the other performer responds in tune, as he shoves his stage partner.

Kimball motions the singers to stop, and Deborah Voigt, the professional operatic soprano sitting next to him, offers a piece of advice. “I really want to encourage you all to sing out,” she says. “The idea is not to blend, the idea is to be distinct.”

Kimball and Voigt coached students during one of the last in-class rehearsals leading up to the world premiere of the Notre Dame-commissioned opera adaptation of William Shakespeare’s comedy As You Like It.

- Shakespeare 400 @ ND

- “A Year of Shakespeare” (The First Folio)

- “A Midsummer Weekend’s Sweet-Shop” (ShakeScenes)

- “Kids vs. The Bard: Who Wins?” (Shakespeare Summer Camp)

Dedicated to the memory of Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, the four-show production ran in April as part of “Shakespeare: 1616-2016,” the yearlong series of campus events commemorating the 400th anniversary of the bard’s death.

“It’s not typical for an undergraduate music department in a liberal arts setting to necessarily have an opera program like ours, which presents a fully staged opera each spring,” Peter Smith, chair of the Department of Music, says. “Then, on top of that, to be commissioning a work and giving a world premiere adds another layer of ambition to what we’re already doing.”

Never before adapted as an opera, As You Like It was chosen by the commissioned composer, British musician Roger Steptoe. The comedy tells the story of Rosalind and Orlando — another pair of lovers hindered by family conflict and mistaken identity.

“I’ve known this play since I was quite young,” Steptoe says. “I wrote a scene back in, gracious, it must have been 1982, that was actually called ‘Another Part of the Forest’ that was for four singers and a pianist.”

Steptoe collaborated with Lesley Fernandez-Armesto, who wrote the libretto — that is, she set the words of the play to the music Steptoe composed.

“It’s a really long play, and if you perform it normally it’s about two-and-a-half hours, so once you set something to music it goes on for much, much longer,” Fernandez-Armesto says. “The brief was to use Shakespeare’s words only, and so I have, but it’s really heavily edited.”

Because the University commissioned the opera, the France-based composer and London-based librettist decided to adjust the setting from 16th-century France to modern-day Notre Dame.

“Roger has even put in this wonderful musical allusion to the fight song that’s just brilliant,” Fernandez-Armesto says. “Everyone collapses with laughter.”

“Well, that was your idea, too, Lesley,” Steptoe says with a laugh.

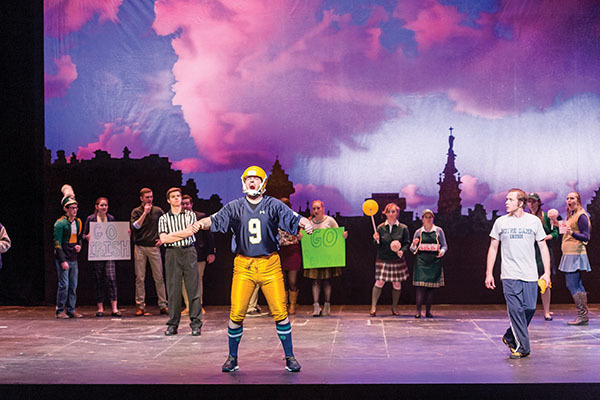

To play off the “Notre Dame Victory March,” the opera included a wrestler dressed in a Fighting Irish football uniform and trumpeters adorned in Notre Dame band gear.

But the allusions don’t end there. “Roger had spoken about lords and ladies and dukes and such, and that just didn’t make sense to me with the Notre Dame fight song and everything else,” director Kimball says. “So I just tried to find a [campus] parallel for every person in the show.”

He made the character of Duke Senior the University’s president, with his younger brother, Frederick, usurping his office. A scene between Rosalind and her cousin Celia seemed a fit for the library — and Kimball staged it with actual chairs, tables and book carts from the Hesburgh Library.

He had put a Notre Dame twist on most of the stage direction but still needed a parallel for the famous “All the world’s a stage” speech, which was moved from Act 2 to become the opening scene of the opera. Then one day the rehearsals with the student cast inspired him.

“We had just been working on developing a character . . . through pantomime,” Kimball says, “so I thought, ‘We’ll make this scene with a teacher who’s giving a course in Acting 101 at Notre Dame, and the assignment that day is to pantomime the seven stages of man.’”

The character of Father Jaques, adorned in Holy Cross priest attire, leads the class, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women are merely players,” he sings, “and one man in his time plays many parts.”

The students follow, pantomiming the infant, whining schoolboy, lover, soldier, justice and old man with cane and spectacles, and end with the seventh stage, “Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything,” Father Jaques intones as he ends the class session.

The journey from commission to Father Jaques’ scene was a long one. The process began much earlier than most Opera Notre Dame productions, starting with auditions in late August 2015. Because the opera is new, the music department wanted to give the students time to learn it, Smith says. An opera workshop class followed the auditions. For that entire workshop, though, the cast didn’t have a typed music score to learn from.

“It was a handwritten score, so that was part of the challenge of last semester. We’d be like, ‘Can we even read this correctly?’” says Camilla Tassi ’16, who plays Celia, as she scrolls through the handwritten-document that’s scanned on her computer.

A fully printed score was eventually produced for the cast, but not until the cast had the opportunity to work with Steptoe. Communicating between France and South Bend, they worked together to adjust notes and directions as they gradually staged the opera.

“We changed a lot of things, because we’d realize, you know, ‘This doesn’t account for enough time to change out of costume’ or ‘Was this really meant to go here?’” Tassi says. “But that’s all stuff that’s part of the process, and I think it’s really important for students to see that. . . . This is the process of creating, so you get to experience what it really takes to put on a production.”

A major change during this creative process was the inclusion of a wrestling scene. Initial plans called for the two wrestlers to be offstage, while the other actors pretend to watch the fight. “That would just not ring my bells,” Kimball says, “because it really is the highlight of the show.”

During the production, a “GO IRISH GO!” poster hangs from the ceiling of the Decio Theatre in the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center. Notre Dame students and the band members circle the stage, placing a mat as Steptoe’s music evokes the Victory March. Charles, the wrestler, stomps onto the stage suited in the football uniform, while the much smaller Orlando meekly makes his way to the mat. The two face each other like David and Goliath.

After Orlando’s underdog victory concludes Act 1, the setting shifts from Notre Dame’s campus to a nearby forest. With the set change, many performers also had to adjust their characters’ personalities — transforming from girl to boy, evil to kind, irreligious to spiritual. New roles are introduced as well, including freshman Katie Ward’s flirty goatherd, Audrey.

“Getting into my character required being okay with letting it all out there,” Ward says. “My character is one that isn’t exactly in line with my personality, so I think I definitely acted a lot with the music and the momentum that it was giving me.”

Ward, like the other students, embraced roles that had never before seen the opera stage. For two weeks leading up to opening night, Voigt worked with the performers to help them vocally form these characters. “Don’t get too disconnected from what you’re singing; you’re chewing on your consonants; embrace your inner diva; your instincts are right,” Voigt would say. Earlier, the students also had worked with another famed opera singer, baritone Nathan Gunn.

Through as much as a dozen hours of weekly rehearsals, the cast and crew turned Shakespeare’s words into song. Hard work, but worth it to be part of a world premiere.

“They were extremely well-prepared, more than any other college group I’ve worked with,” Kimball says. “This is an extremely difficult modern piece to pull off. It has to seem effortless like a comedy, and they did that.”

Kit Loughran was this magazine’s spring 2016 intern.