For the last several years, whenever I thought about January 20, 2017, the day Barack Obama leaves the most powerful office in the world, I also imagined that it would be as if Obama were stepping away from the podium and walking to a nearby table where he would close a book. The imagined book in this imaginary scene told a story, a long story of hundreds of years of battle and sacrifice that had just come to an end, one version of the story of the struggle of African Americans to gain full purchase as citizens in the country where they were born, lived and died, a struggle that had ended with a victory in the effort to gain an honored place at the very center of American life. Obama would be the one to close the book because his life and career were the last chapter of that effort, its ultimate fulfillment.

As Obama finishes his term, one push of African Americans — and as such, because blacks are so deeply entwined in the history and daily life of the country, the nation as a whole — will have come to a close. The story of that push began in Virginia in 1619 with the advent of black slavery in Jamestown; it continued through the revolution and the establishment of the United States as a separate nation, on through the bloodletting of the Civil War and Reconstruction, to the moral apotheosis of the 20th century and the civil rights movement. It was a story embodied in the lives of some who led the fight: Richard Allen, Martin Walker, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, A. Philip Randolph, Fannie Lou Hamer, Malcolm X and, finally, Barack Obama.

In what seemed to be a confirmation of the gains wrought by the civil rights movement and its pre-eminent leader, Martin Luther King Jr., came the election of a black president, elected twice, which was thought to indicate a kind of acceptance and accomplishment of blacks. That a black man could be elected president of the United States was unimaginable until recently. It having happened, twice, made it seem as if the narrative of black struggle had reached a triumphant climax, that all the faith and pain and sacrifice had been redeemed, and that America, so often wrestling with the facts and contradictions of its history, customs and realities, could stretch and change and renew itself. A great deal was left to be done, but it was a cause for celebration.

It still is. But the story that ends with Obama also has an epilogue that might be the painful introduction of another tale. This account will relate the bitter knowledge that the 400 years of struggle and aspiration was not enough, that the nation is still susceptible to strands of violent emotion and vulgar irrationality, and that too many citizens are still mindlessly stoking fires of social conflict and disarray in a fashion that could flare beyond society’s ability to control or extinguish them.

Before I go any further I must utilize one of our newer clichés, full disclosure: I am African American. I’m proud to be so, and as yet would not have had it any other way, though there are days when I resent the unearned and unrequested baggage such an identity can require. But I am proud of my family, my forebears and, as such, proud of, to use the vernacular, my people, a people who have stood up to persecution and violence sanctioned and unsanctioned, endured, and come through with integrity, humanity and honor. I do not, however, presume to speak for any African American other than myself. I have come to a painful belief that in America, in the end, every black man and every black woman, like every other citizen, fights his or her own war. We African Americans can sometimes come together to work on specific problems, but I believe it is naïve in the extreme to assume or presume that all African Americans see things through the same lens or will come to the same conclusion of how to react to a particular issue.

To emphasize another layer of my identity, I think that we Americans, by which I mean all citizens of every group and identity, are at this moment of social strain suffering from an absence of nuance. We speak in generalities to account for all of the legitimate differences and layers of experience we live with, but every story about race in the United States is a different story, including — and I think this is a dawning realization for many citizens — those involving whites. And we tell each other and ourselves stories in order to understand each other and ourselves. However, an underground struggle for primacy has erupted, as though a long-suffering family was fighting to claim the title of which member was most sinned against. And the subjective nature of such claims, which often seems obvious to a particular person or group, short-circuits any understanding. And without understanding, what?

It had been my hope, with the 2008 election of Barack Obama, that we Americans had bought some time to distance ourselves from our troubled past and to gain perspective. That we might out run history, or to put it another way, fate. That the United States could continue on its bumpy slide toward something I’d come to think of as “racial normalcy,” a new status quo that would reflect current demographic realities and would allow for a more peaceful transition to the coming demographic change (as soon as the 2020s, certainly by the 2040s), when, as in the state of California currently, whites are less than 50 percent of the population, or just another group, albeit a large one, and one endowed with considerable economic power. That whites could see that circumstance as the next phase of the nation and continue accordingly.

I’d hoped that we as a nation could continue grinding toward that new racial configuration, which would not occur overnight but could generate balance and predictability, and wouldn’t get too out of control in any one direction. And I’d thought that Obama’s presidency could mark a huge moment in African-American (and therefore American) history, a marker in the progress of African Americans to “just another group” in the mosaic (regularly contested even though we have been here since the very first day). If African Americans could achieve this place in a new society, then by default every other group that finds itself taking a turn as the scapegoated outsider in 2010s rhetoric — Latino immigrants, Muslims, LGBT — might also gain an established presence. I didn’t expect this next status quo to emerge tomorrow, but I thought it was well under way and would progress generationally, as it had in the past.

Now, I’m not so sure. But that’s who I am, and what I had thought, and what I had hoped for. Until November 8, 2016.

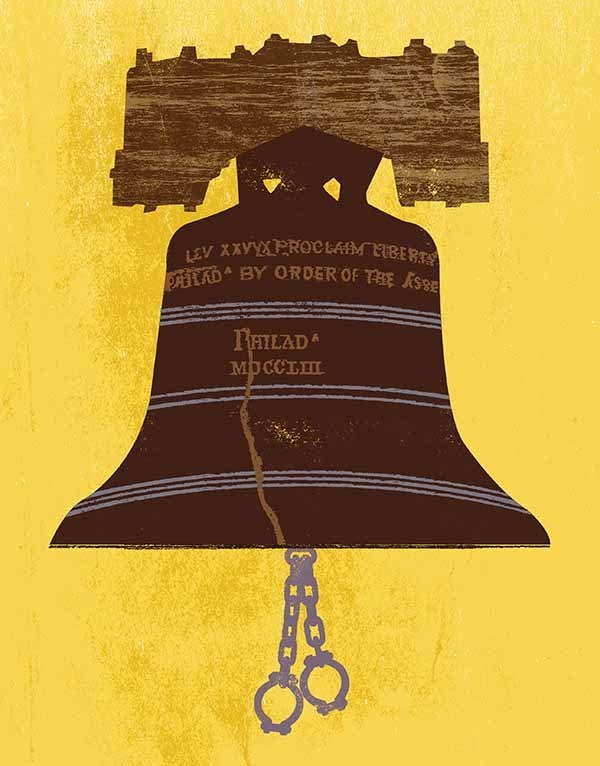

There is an irony, both tragic and celebratory, at the heart of our society: young people of color grow up hearing about the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, and they believe it. They want to hold the nation to its promises, they want to belong and be Americans, free and equal, as they understand those terms. And every generation understands the promises of our founding documents a little more intensely and insists a little more on the full implementation of those promises.

This is, I think, what lies behind Black Lives Matter and many of the other protests enacted around the nation. In another country, one which has not made such promises, there would not necessarily be such a sense of failure. Black Lives Matter protestors are expressing a belief in the system; framed this way, the question becomes: Can the system live up to that belief?

This is why looking at Obama as an individual, whatever one might think of him as a politician (and setting aside, for the moment, the irrationally partisan and race-driven attacks upon him, there are dissatisfactions a reasonable person may have with his performance), is worth our while. In my view, in many ways Obama is the most important black man in history, beyond Martin Luther King, beyond Nelson Mandela. This is not because of his celebrity, accomplishments or lack of them while in office, but rather because of the way he matter-of-factly mastered and rose through the tests and trials of U.S. society. To put it simply, he won the highest political prize of our nation through playing by the rules. He battled and prevailed in many different arenas: academia, law, publishing, politics. He learned how things worked, how achievement is accomplished in the secular world — an important point because so much previous outsize black accomplishment had been based in religious institutions. He showed a path.

Obama’s life and career is a model for blacks and people of color on how to progress to the highest reaches of our society: work hard, get educated, get qualified, learn how to contest the career and workplace circumstances you find yourself in and, with a little timing, a little luck, who knows what might happen? He mastered the politics of Harvard Law School, the politics of Chicago, the politics of the Democratic Party and the politics of national elections by learning the traditions and rules of each context. His was, for want of a better term, a “secular” triumph, the next step in African-American progress in society, following on black athletes and business executives, stating his case to the electorate and receiving their endorsement.

One would think that whites, whether they agreed with his politics or not, would see his career and achievement as something to be celebrated, something to be pointed at, not because of any “Kumbaya” racial fellow feeling but because it encouraged millions of young blacks and other folks of color to believe they had a chance in our society. That the way for them to advance their hopes and dreams was in the library and at the ballot box, not in the streets.

This, of course, was not the lesson everyone took from Obama’s success. Many whites interpreted his success as a mortal threat to the future of the nation, and after an eight-year drumbeat of opposition and rancor have in reaction elected a successor who, on the face of all observable data, is uniquely unsuited and unqualified to be president, and whose principal talent seems to lie in not discussing in measurable detail any of the myriad and subtle issues and dangers facing our nation and society. It was enough to scream “Make America great again.” Left unsaid in that reductive slogan was exactly how and why America was no longer a great country.

But I should stop there, as I do not wish to go too far down the road of political mockery and snark. There are much more important things I wish to discuss, qualities that go beyond the outcome of any one election, that go ultimately, I think, deeper than politics. They go to the figurative soul of the nation and can continue to be ignored or toyed with only at our deepest peril. Unfortunately, we have allowed these issues of national soul to become entangled in partisan politics, an entanglement, I fear, that was probably inevitable.

The way Obama was treated as president, whether through the obstinate opposition of Republican legislators or the disrespectful disdain of groups such as the birthers and the Tea Party, is often excused as an exercise of tactics, a lawful utilization of the rules that is open to any partisan. But I am deeply saddened to realize just how much what might have been construed as sincere progress amid American complexity — gained after centuries of struggle and survival, and decades of applied strategy and hard work and following the rules, all of it paid for by the sacrifices, including their deaths, of millions — was seen as defeat by many whites.

Obama’s election was construed by some not as a healing or the next step in the history of the nation but as a wound, an insult in the old medical sense of the word, meaning damage to tissues and organs, in this case those of the body politic. It was also a wound in the sense of an imposition of humiliation and psychic pain. For the eight years of Obama’s presidency that wound was deliberately salted by words and actions beyond tragic to those who hope for a nation that can live up to its founding documents and provide sustaining shelter for all of its citizens. And I’m pretty sure I’m not the only person, black, white, Latino, Asian or Native American, who feels that way.

I cannot help but feel that the tactics and the overall strategy, especially if it was merely political, has endangered our civil society, our nation. Not because those tactics prohibited Obama from achieving some of his political goals. In my view, the message that was sent, deliberately, by these tactics to blacks and people of color throughout Obama’s presidency was: Even if you make it to Harvard Law School, become a U.S. senator, win not one but two elections to become president and happen to be black, you are still illegitimate. You are not good enough. You are a usurper and a threat to all that is good and holy.

Whether a sincere belief or the implementation of political tactics, such implied messages do not enter into a vacuum. The way Obama was treated by large segments of the population tells other segments of the population that trying to live up to the rules and standards of the wider society doesn’t really matter, because it won’t ever be good enough. You, who on one day are vilified for not punishing bankers, will the next be vilified as a socialist determined to undo capitalism. You will be accused of being a “Muslim,” though you testify to Christian belief and have decades of publicized Christian practice behind you. Many will state firmly that you are not a citizen. Your academic accomplishments will be questioned, undermined and, in another strange twist, even mocked. Almost anything someone can think of to say, no matter how scurrilous or unlikely, about your mother, your wife, your children, will be posted to the Facebook newsfeed and passed around the country through fiber optic lines at the speed of light. And on and on and on.

A large segment of the populace will not understand that these are all dangerous things to say and do, even if, under the First Amendment, they have a right to say them. Because to recognize that danger would be to admit that our country was not as simple or innocent as they want or need to believe, and that such recklessness begins to undermine the social contract and unravel the social fabric of our society. That contract, that fabric, is a fragile thing, rightly celebrated as the rarest of accomplishments in human history and in need of being handled with care and respect. Throughout the persecution of Obama and continuing into the campaign of Trump, however, that respect has been missing. And we seem to have forgotten as a body politic that others were watching — our children, including the white children at grammar schools who began to terrorize classmates of color with violence and chants of “Trump! Trump! Trump!” as well as people from other countries who look to the United States for guidance, example and salve, and who, listening to the words and ideas that were thrown around with such impertinence and even glee, began to wonder if we had lost our minds.

Speaking for myself as an African American, I find it dispiriting to confirm my paranoia that many whites, apparently, still prefer the old ways and are transferring those preferences to their children or, at the very least, do not care enough about the way things appear to others to take them into account or even value them as having weight. This unwillingness to hear the articulated concerns of fellow citizens — exemplified by knee-jerk reactions to complaints about police killings — becomes, I think, a subtle form of white supremacy, a way of saying that the desires and perceptions of whites take precedence over those of everyone else. It is a way of saying, quietly, that everyone else is subordinate. It is, in fact, a form of childishness, the sort of selfishness one expects from a toddler, writ large. And this mindset is something that, in the coming years, those targeted by such thoughts and language are not going to accept, so it will be a source of ongoing friction that may burst into flame.

Perhaps whites are unable to perceive the provocation in the language of the Trump campaign and many of his supporters (whatever Trump may do as time passes to try and call it back). Think of Trump’s reference to “the” African Americans, “the” Hispanics, “the” Muslims, and the way that article distances those described groups and implies that they are not part of a normal mainstream. Or, more obviously, his reference to Mexicans as “rapists.” Or the promotion of internment camps, modeled on American WWII treatment of Japanese citizens, by Trump surrogates. Personally, I think some whites can not only hear that provocation but enjoy it, and others who do not enjoy it search for ways to ignore and excuse it. In any event, I believe all Americans should learn to hear it, because it is so crucial to the ongoing daily life of the nation. Choosing the language and posturing of the Trump of the presidential campaign is a betrayal of the citizens of those disparaged groups, who have paid taxes, served in the military, volunteered in our common civil society and been law abiding co-workers, neighbors and citizens. The usage of and reveling in such language was a deliberately chosen ignorance in service of a nostalgia-fueled half-dream of a time that never was, and can certainly never be.

Even in the best of times we underestimate just how thoroughly race is laced throughout our society — it is pervasive, in everything, and everywhere. Bringing this up can, I understand, make whites uncomfortable. The history of racial discrimination in the United States is a painful and shameful legacy to be attached to, especially when one feels no personal connection to the actions of the past. Also, such discussion of race can be construed as striving for power within an interaction, in the sense of trying to impose guilt or extract unearned advantage. In the best-intentioned of situations the injection of race can wrong-foot a conversation or situation, and thus it becomes, I think, in the interest of whites to avoid all mention of our racial history and the complications that now exist. As a result, even those whites who consider themselves “woke” — aware of history and allied to the oppressed — can find themselves preferring a zone of silence around all discussion of race. And blacks and other nonwhites are not immune from the awkwardness surrounding race and may choose avoidance or be either unintentionally clumsy or deliberately provocative in such discussions in ways that become unproductive.

But such awkwardness, shame and avoidance prevents us from intervening when race truly should be discussed. As Obama leaves office and is succeeded by Trump, we are in one of those periods. The “silences” in U.S. life and experience — so much unsaid, so much disagreed about, so many regrets — continue to warp our normal political discourse. No common language is available to those who urgently feel the pressure of the past in the present or who feel absolutely no connection to the events of the past or who — like some of Trump’s most extreme “alt-right,” white nationalist and white supremacist supporters — glory in the cruelty and suffering. And white, black, Hispanic, Asian, Latino have different layers of memory, different “time zones” of experience, different zones of perception: How can we expect them to reconcile?

I have thought for some time that the next moment of progress in building our more perfect union was going to have to come from whites. Whites are going to have to decide among themselves what kind of nation they want, whether they want to pursue a chimera of the past and try to maintain a position of dominance that will trigger reaction and conflict or whether they can imagine and work toward “liberty and justice for all.” They have to decide whether they truly believe that “all men are created equal.”

Those next steps of progress will involve things only whites can do: stop fanning racial conflict, truly end segregation (which seems to be increasing and hardening), see that every child in America has a real chance at an education that will equip them to compete in the new economy (many white children need this guarantee as well). Class may also enter the discussion here, but it is an open question as to whether there will ever be a time when class interest is more important to white voters than racial solidarity. And, given the embrace of the rhetoric and ideology of Trump, white racial solidarity appears as ferocious as it’s been in decades, after the presidency of Obama.

After Obama, America stands revealed to itself, facing further self-knowledge, caught in a moment when lessons of the past are not going to be of much help. It is time, finally, to imagine a sustainable future as the past carries too much grievance, too much baggage, too much pain. Making America great again is in truth yet another re-litigation of the social contests of the 1960s and ’70s, yet another battle over the challenges and gains of the civil rights movement, and whether they will be a permanent fixture in American society.

In one example, white southerners fought for decades to loosen the remedies of the Voting Rights Act and ultimately claimed that progress had been made, and therefore there was no longer any need for such supervision. But upon prevailing in the Supreme Court case Shelby County v. Holder and gaining relief from strict federal supervision of state and local polling practices, states such as North Carolina began immediately devising ways to restrict African American participation in the political process, which we saw fought over throughout the 2016 campaign. It was as if the struggles of the past 70-some years had not resulted in progress but had been merely a timeout in the views of those who intend to dominate our society in the name of white control. (And there were, apparently, enough of them to make the imposition of the oppressive rules and procedures law.) This revelation is for me a painful knowledge that we have much further to go than we thought, further than we may want or think we can go. But the truth is, we are likely just beginning to enter into a true accounting and discussion, at long last, of American racial history and will have to decide if we want to go forward or go back. There is no staying the same. And more acutely, and perhaps more painfully, there is no going back.

Trying to understand America in 2017 is like trying to solve an artificially intelligent Rubik’s Cube, one programmed to outwit all attempts at solution by continually reshuffling itself. Perhaps America can’t be solved. Perhaps it can only be lived out, and we have only a 50/50 chance of transcending political estrangement and polarization for the good of the future. Do enough of us see it as necessary to try, or do too many of us want to reach backward for an allegedly simpler and therefore better time?

In the light of the 2016 campaign season and its outcome, for the first time in my adult life I wonder if we can recapture the urgency and majority that 50 years ago led the nation to push for a future that consciously broke with the mistakes of the past. More than that, I wonder if enough of us even want to. Or are there too many pressures and problems from too many different directions that exist in so many incompatible contexts that the fault lines overload, maybe by accident, without us intending or noticing it happening, making the saga that one might have hoped was brought to a close by Barack Obama look in fact like a children’s story.

Anthony Walton has contributed to the magazine for more than 20 years. He lives in Brunswick, Maine.