Enderson

That’s his real name. Enderson Barbosa Santana. They called him o Bebê. It’s not like he had a baby face or anything. It’s hard to know why, when people get a nickname. There is probably a story behind it, but that is what they called him.

At home, he had a kind face, warm and caring. On the street, he was a badass, someone you would respect, as in, cross the street and walk on the other side to stay out of his way. He was a gangster, a tough guy, and he wasn’t putting up with any BS.

I met him at the emergency room of the regional hospital in Boa Vista, Roraima, the northernmost state in the Brazilian Amazon, where I was chaplain. It was about 10 in the morning on a Friday. He had been shot just before dawn. His wounds were fresh and blood was all over the gurney. His right leg was in traction and he had a big bandage on his abdomen.

There were two shots. The first one fractured his femur and, with that, he fell to the ground. One would think. The second shot entered just above his navel, ripping into his intestines and lodging in his spine. No exit wound. That’s how pathologists say it.

When I found him, he was hovering between life and death. He knew it and didn’t seem concerned. The pain came and went, like a giant unbearable wave, every five minutes or so, taking with it, every time, a piece of his soul. I suppose that is what made not dying a secondary concern.

Enderson was waiting in the corridor of the hospital because the staff couldn’t find a place to put him. His cot was a stainless steel stretcher on grimy wheels. On top of that, there was a wooden backboard, probably right out of the ambulance. He was tied to that so he wouldn’t fall off, and handcuffed to the gurney because he was under arrest.

He was naked except for the bloody green sheet that lightly covered him. When you get stabbed or shot, they cut your clothes off with scissors at the emergency room. It is a question of hygiene, I guess. Enderson couldn’t have cared less right then.

At his head, sitting on a stool, was his girl. She was hunched over, clutching her own belly with her face to the wall. She was little more than a teenager and three months pregnant. It was to be her second child with o Bebê. Their oldest was already 2. That’s how I knew what he looked like before he was shot. They showed me a picture. They looked like a young but happy family.

Enderson was disoriented. He wasn’t even really sure what had happened. The room was spinning, between the horse’s dose of dipyrone they had given him and the two quarts of blood he had lost. I took his hand. He got me bloody. And squeezed. I spoke softly, as one would speak to a scared colt to calm him. It seemed to help, in the same way a foot on the floor will help a drunk to make the room stop spinning around.

It is a game, of course, but when dealing with pain it often works. Especially when there has been an accident, because the victim is not expecting his pain. You take his hand and tell him to transfer the pain to you. As if by conduction. And it seems to soothe the unbearable. I think it’s just knowing that someone is willing to share it.

It’s knowing that someone on the planet is willing to get blood on them. Get involved in your story. There has to be contact. A hand is best, but you can put your hand on the victim’s forehead, too. That works pretty well. Or on his chest. Where the heart is.

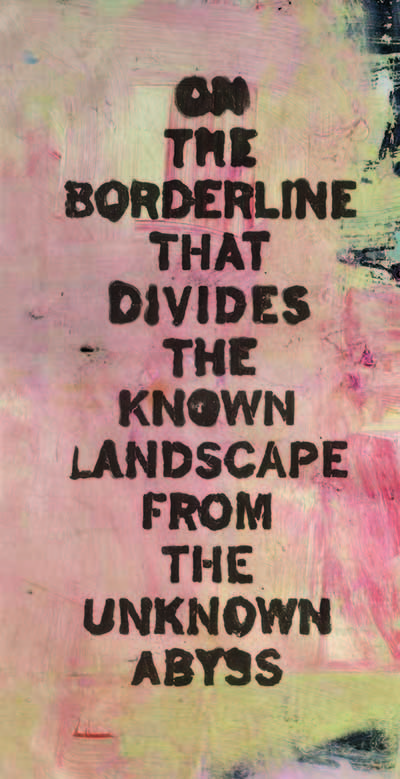

Enderson was waiting for surgery. They had to open up his gut and repair all the internal damage. If not, he would have certainly died of gangrene after about three very painful days. That is the worst death, the one soldiers most fear on the battlefield. If that were the case, it was better to bleed to death before it happened. He was pretty close. He was on the borderline that divides the known landscape from the unknown abyss.

We had gotten through six or seven waves of pain, but the staff was going to throw me out. Visiting hours were over. I had to leave, so I took his girlfriend by the hand and asked her to stand and place her hand where mine had been. Stay here, I said, he is disoriented. And she did. She stayed there for six months by his side. She was gone three days to have her baby. Then she came back.

The newspaper said he was arrested before dawn on Friday by the Brazilian military police, that he was armed and dangerous, and that the other three young men arrested with him were not hurt. They all had gangster nicknames and police records. They only shot o Bebê. The papers used his nickname, as if perhaps readers might know who he was. The police knew, for sure.

The strange thing is that the bullets were all front to back. First in the thigh, and then in the gut. That means he wasn’t running away. He was facing the officers who were trying to arrest him. If in fact that is what they were trying to do.

Close to 3,000 young Brazilians died last year in altercations with the police. That’s almost 10 per day, as many as the victims of 9/11.

Murders are also on the rise. There were 60,000 in Brazil last year. Gang versus gang, payback, drug debts and love triangles, never at a loss for a motive.

O Bebê didn’t die, though. They missed his aorta by about a half an inch, and they missed his heart by about four. By law, he had a right to medical treatment and a fair trial. At least, in theory. He had not been formally accused of anything. And so his odyssey began.

His first operation ended that night. They opened him up from pubis to sternum so they could root around inside him and repair any internal injuries he might have. They sewed him up with 25 thick stitches, the kind you might see on a horse that got cut. I found him in the B-wing three days later. He was smiling and said he was expecting me. It was obvious to him that I would be back. He had already marked me with blood.

I made an effort to stop in every day. Enderson never moved from his hospital bed. He couldn’t move, because his leg was still in traction and he was still under arrest and handcuffed to the bed. So for five minutes a day I held his free hand, the way I had done that first day. It was the least I could do. It was all I could do. He was counting on me. I helped with the little things, sometimes. He wasn’t ashamed. I was family by then.

If he were sleeping when I came, he would open one eye, without moving, and I would watch over his dreams. Sleeping was better than being awake, I guess. I usually wouldn’t say much, but sometimes I would encourage him never to lose hope, that this was like climbing a mountain, that it was hard but, with patience, he could make it. I hoped that was true.

Enderson was on the waiting list for the other surgery, the one to repair his fractured femur. The hospital was full of fractured femurs. When there were survivors from motorcycle accidents, they all had fractured femurs. There was one operating room, one surgeon and the hospital tended to run out of the titanium bolts used to fix those. So there was a long line, and Enderson was always at the end of it. He was black and young and under arrest. They never did that operation. His femur eventually mended, but 2 inches shorter than it was supposed to be. He was sentenced, by triage, to be lame for life.

After six weeks, I went to Rio for a meeting. When I came back, o Bebê had a new tube in his nose to drain off some nasty green liquid. I got worse, he said. It was true. The surgeon had missed something when he repaired the intestine. It didn’t show up as long as he was on antibiotics, but when they took him off, he got peritonitis. The next day, his bed was empty.

He had emergency surgery. They took out several feet of gut. He ended up with a new cut in the same place and a colostomy bag. I found him in intensive care, in a panic. We got hold of his mom and his girlfriend on my cell phone. Just to say he was alive. They didn’t know where he was or how long he would be there. He wasn’t supposed to talk on the phone because he was still a prisoner. But there were no guards in intensive care. That’s how it rolled. Every day was a game of roulette. The Russian kind.

He went back to B-wing after a few days and started on his legal battle. He had to pay off a lawyer to pay off the judge to move on his case, and nothing happened. Finally, the doctors said he was well enough to leave the hospital, even though he couldn’t walk and he still had a colostomy bag. He was taken to jail pending prosecution. He still had not been formally charged, but the local newspaper had already declared him guilty.

He was nervous that day. He said it was fine, he had friends and cousins on the inside and they would protect him. His mother knew how to move the papers around. They were no strangers to jails and judicial process. But he was still sick, and he came back sicker.

Two months later, he was in intensive care again. In prison he had no way to properly clean and change his colostomy bag. He needed alcohol, but that was off limits. It got infected and he lost a few more feet of intestine. The new cut down his abdomen wouldn’t heal. This went on for months. He still couldn’t walk and he was still handcuffed to the bed.

Enderson said he would rather die than go back to jail. That was hell. If they were going to take him back, he would have killed himself, I think. He was in chains, but he had resources. He gave the orders in a shady world most people never see. He would have found a way. Anything, to keep from going back to that place.

In the end, the judge put him under house arrest. The local jail didn’t have an infirmary and the warden refused to take him back under those conditions. It was a good thing. He could be at home with his two boys. He could clean his wounds. He could watch the television shows that made him laugh. I used to take him pirate DVDs of Jackass at the hospital. Those were his favorite. He was one bad dude but just a little kid, at heart.

He left in a wheelchair, 40 pounds lighter and diminished in every way. But he was alive and grateful for that. He still had his networks for commerce and protection. But now, he was counting on me, too. For hope, maybe. Hope that there could be another way.

The last time I saw him, he reached up and touched my face, you know, the way brothers sometimes do. They kiss your hand, too, in Brazil. It’s a fraternal thing. The younger brother asks for the blessing of the older, and that means you are supposed to take his hand and kiss it. He responds by kissing back. That is how we bid farewell. May God bless him.

Evanildo

I found Evanildo on a Sunday in the emergency room annex of the Roraima hospital. It was about 10 in the morning and he was sitting on his cot, dirty, wearing only his underwear and the regulation green hospital sheet, soaked in his own blood. He smelled of sweat and fear. He was alone and not speaking. He looked like a caged animal.

He had been arrested the night before. This time the military police were not the principal aggressors. In fact, I think they saved his life. Evanildo had broken into some shop and the owner caught him. The owner had a machete, and he was mad.

Evanildo was no expert at burglary. He was, in fact, naïve. He didn’t use drugs and had no notion of gangs or fights or jails. He did something, but I’m not sure what or why.

The shop owner, I am assuming with some help, managed to chop off Evanildo’s right hand precisely at the wrist. He gave a good chop to the left, too, but there he hit the radius bone. Either the blow was too weak or the machete wasn’t sharp enough. After that, Evanildo escaped onto the roof, arterial blood gushing from both arms. There, the shop’s neighbor shot him in the groin. It was a close call. The neighbor was not a very good shot, thank God.

An arm without a hand is shocking. The first time I saw that in the hospital, it was a boy who was only about 15. An older brother had cut off his hand. He didn’t believe his own sibling would really do it, but the older boy was a drug addict. He told his kid brother he would cut off his hand if he didn’t give him all the money. He was desperate. Drugs do that.

A wrist without a hand is like a neck without a head. It’s worse, I’m sure, if it’s your own; if yesterday it was there, and today it’s not. Victims feel the amputated member even when it’s gone. Some call it a ghost limb. It often happens when it’s a hand that’s missing. A hand has a lot of nerve endings. It’s as if it were an extension of your brain. Part of your personality, your character, part of everything you had ever done.

Evanildo had lost a lot of blood. He was fighting for his life on the neighbor’s roof when the police van arrived. He was saved from a lynching but arrested for burglary. The police took him to the hospital. No family member came for him. He hadn’t eaten breakfast because he couldn’t move a spoon from plate to mouth. He had not bathed, either. He was handcuffed to the bed by his foot, because he had no right hand and his left was full of stitches. The handcuffs were too tight on his ankle and forced him into an uncomfortable position. Sweaty, bloody and caked with dirt, Evanildo breathed rapidly, like cornered prey that doesn’t expect to survive the next few minutes.

Evanildo’s mom was in Manaus. She went for one of those big noisy meetings for evangelical Christians. She found out about her son’s plight and just stayed there, praising the Lord. Evanildo’s girlfriend was only 14. She was five months pregnant. She didn’t have bus money to go to the hospital and wasn’t old enough to stay with him.

When there is no family member to stay with a patient, auxiliary staff are supposed to step in, at least to bathe and feed those who can’t do that for themselves. But they said, no, not that one. He was a criminal. Caught red-handed, they said. Yeah, in a bad way. Bright red. That day, I took care of it.

The local newspaper took sides with the lynch mob. The shop owner appeared in a photo, brandishing his machete, bragging about what he had done. They made it sound like he had defended the whole neighborhood from a mass murderer. I guess the crowd likes lynching.

It isn’t easy to chop off a hand. There is more to it than just taking a lucky swipe in the air. You have to hold a man down, immobilize his arm on a hard surface and take a precise swing with a sharp blade. Butchers are good at that. Then, they held him down again, blood and all, to go for the other hand. It’s something straight out of a baroque woodcut; the judicial horrors of long ago, executed by an angry mob and applauded in the local paper.

Evanildo was not armed. It is interesting that his last name was Ferreira. The shop owner’s name was also Ferreira. He was white. Evanildo’s mom was black, from Bahia, pure Afro-Brazilian. Evanildo was mixed race, what they called mulato. That’s an ugly term. It means you are a mule. Mules are half-breeds. They are infertile and they are slaves.

Evanildo told me he had no father. If he cuts off your hand, I guess you can consider yourself disinherited. I suspect that Evanildo wasn’t there to steal anything. He went to ask for paternal assistance in his hour of need. His own child was on the way and he had no way to feed it. The old man refused and things got ugly. His bastard son with that black woman was a problem for his official family. Maybe. I can’t be sure. But it’s unusual that the pieces fit so perfectly. Nothing happens by chance in this world.

While he was in the hospital, Evanildo never had any family member stay to take care of him. For a month and a half, I fed him lunch. Spoon to mouth, like a little kid. He liked everything mixed together. I had to take farinha in secret, because the hospital didn’t provide any. Once we became friends, Evanildo confided to me that he was hungry all day long. I started taking soda crackers and juice. He would devour an entire package at 10 in the morning, like a growing adolescent. That would keep the hunger at bay for half an hour.

Evanildo’s mom stopped by a few times but never stayed long. The die-hard evangelicals tend to abandon family members when they get into trouble. Pastors will tell them they have to. They say that when bad things happen to you, it means you don’t belong to the chosen few. If you are not among the chosen few, you could drag your family down to hell with you. That’s what they believe, anyway. So they cut all ties. She was a superstitious woman, deep down. Evangelical voodoo. Her world was inhabited by demons, ghosts and evil vapors.

The girlfriend came about once a week. When she couldn’t make it, she would call me on my cell to see if I could put Evanildo on the line. It had to be when the guards were dealing with some other prisoner. There were always at least three or four in the hospital. Prisoners weren’t allowed phone privileges. When she went to the hospital, it was usually in the afternoon. I would have to leave money for her bus fare home hidden in the drawer of the bedside table, because prisoners couldn’t have money, either.

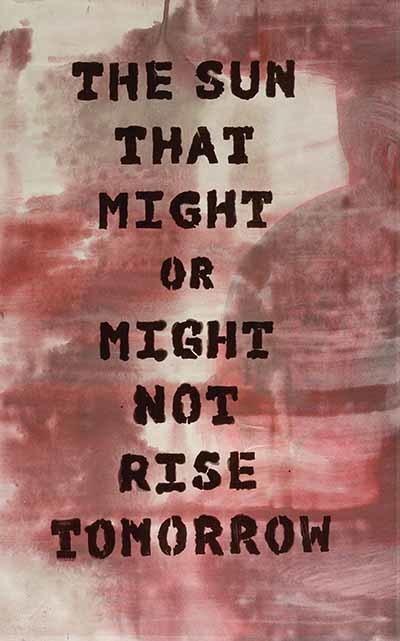

Evanildo felt abandoned. No one was going to believe him, and he knew it. He accepted his situation without complaint, consternation or amazement. On the one hand, he had provoked it. On the other, life had taught him never to trust, not in people, not in the world, not in the sun that might or might not rise tomorrow. He was like a wild animal. He had learned to expect death at any moment. He belonged to a class of people the civilized world considers subhuman. They have no rights. They are excluded, a priori. Their lives are disposable and unimportant. I suspect that is the way it is for most of the human race. This is why terrorism in Paris is news, terrorism in Pakistan is not.

Evanildo lived the moment. It was all he had. He recovered from his wounds and the day drew near when his guards would take him to jail. There he would have to wait for a trial, something to legitimize the cards he had been dealt. He was saved from a lynching to be punished by the state. Whatever they gave you for burglary. The newspaper said attempted murder. The press had already condemned him. It was a done deal.

Since the days of the Roman Colosseum, Evanildo had been predestined to a lengthy sentence. Disfigured as he was, he did not elicit mercy. On the contrary. People were horrified. The crowd seemed to see an amputee as some kind of monster who, for some reason, deserved to suffer. He would be given the maximum sentence, I was sure. Not even Caesar would dare to apply jurisprudence. His job was to please the crowd and he knew it.

I taught Evanildo to ask for the public defender. He didn’t know what that was and he forgot how to say it every 15 minutes. I think he really had no hope. He went to jail resigned to the fact that in there they would do whatever they wanted with him. The pariahs in our caste system accept things as they are. They have no choice.

I didn’t get a chance to say goodbye. One day he was just gone, and I never heard from him again. I went to his room, and his bed was empty, as if he had died. I had no way to visit him in prison. It was really hard to get authorized. I missed him. He was a criminal, they said. Even the social workers were self-righteously negligent in handling his case. But I fed him with a spoon. As if he were my own kid.

In his room, on the B-wing, there was an old man with cirrhosis. He couldn’t walk or talk any more. He reeked of ammonia and was waiting for surgery so he wouldn’t die so soon from the hard drinking he had done all his life. His adult children took turns caring for him. There also was a boy of about 13. He was skinny with curly blond hair and had a broken femur from a bicycle accident. He had been run over by a motorcycle. His parents took turns tending to him. His name was Aurelio and, little by little, he had become friends with Evanildo. Aurelio was really innocent.

At the beginning, Evanildo didn’t talk to him. He didn’t expect that they would be able to get along. But as time went by, they became like brothers. They knew I sometimes had these little coconut squares in my knapsack in case I got hungry on the road. If they teamed up, they could con me out of them. Sometimes when I arrived, they would be singing together. Just to pass the time. I think Aurelio missed him, too, when Evanildo went away to prison.

His delinquent friend. Everyone should have at least one.

Thiago

The night before Thiago died, I ran into him on a street corner in Santarém. I practically knocked him down. I was out running in the dark, and he was walking home from the pool, no shirt and swim goggles on his right shoulder with the strap running through his armpit, as if he had an extra pair of eyes on that shoulder. Thiago was always original, though it wasn’t as if he tried to be. It was just that he was so uninhibited that things came out unusual, seu jeito, as they say in Brazil, his way.

I came up from behind and almost didn’t recognize him in the dark except for his tall form and characteristic gait, kind of a springy urgent amble, what you would expect of a dancer who also plays soccer. That I would run into him seemed obvious. Nothing ever surprised Thiago. Everything just sort of happened to him. Life was like a boat that moved under the feet of river people. They managed to always expect the unexpected.

That was a good thing in Santarém, because transportation generally happened over water. Roads for cars and trucks were few and badly maintained. There was a bus station, but only three or four buses were coming in or out on any given day. By contrast, the dock on the riverfront was enormous and busy. Life happened there. In fact, the city has been in that spot for the last 400 years because that was where the Amazon River met the Tapajós.

In Santarém, many young men are named Thiago. That is on account of a bishop who ruled like a feudal lord there for decades. His name was Jimmy Ryan, and he died in 2002. He brought lots of foreign money into the city to fund charity institutions. He also hired lots of people to do nothing at all. They called him Dom Thiago and named their boys after him in gratitude for his boundless generosity.

Our Thiago never met Dom Thiago but bore his name, same as about 30 percent of all youth of masculine persuasion. Because he was so impulsive, he took meeting a friend in the street in the dark as the most normal of occurrences. There was no hi-how-are-you business. He just picked up the conversation wherever his vagabond mind was at that particular moment. Thiago was as spontaneous as anyone could be. It used to drive Felipe crazy.

Felipe was his brother, older by a year, and in public he was usually making an effort to get Thiago to settle down, be more careful, not call attention to himself, watch out for this, take care of that, not bounce the ball in front of the car or say bad words in front of small children and little old ladies. Thiago never paid any attention. He had so much fun.

Their parents were separated, and the boys lived with their mom in a house on the edge of an old airstrip. Their mom had a huge collection of orchids that took up half the house. They hung in wooden pots, each variety in just the right place for temperature, humidity and sunlight.

The night I ran into him, Thiago was obsessed with the flip turn, you know, what swimmers do at the end of the pool to turn around and go back the other way in a race. He wanted to know if I knew how to do it, if I could explain it to him, so that next day he could get it right. I don’t know why he thought I would know. We came to his corner. He put his right arm over my left shoulder for an instant. I could feel his vacant swim googles as they watched the horizon. Then he went on his way and I went mine. I could feel his friendly sweat running down my arm. The following day, practicing flip turns at the pool, he died.

He was 17. The dreams had been about him.

I had been dreaming about my dad. I would meet him walking down the same street where I bid farewell to Thiago. It’s the one that connects the city park with the only overland route to the rest of Brazil. My dad had died 10 years before. We all missed him enormously, and I thought he had come for me. So I was watching the traffic, expecting a spectacular accident to end my pilgrimage on earth. But no. Dad had come for Thiago. As a good angel, a guide to take him through unknown territory. I was surprised.

There were rumors that Thiago had been on drugs, but they weren’t true. Others said he hit his head on the bottom of the pool, blacked out and drowned. Also false. He simply lost consciousness and went to the bottom. The boys swimming with him noticed immediately and fished him out. He regained consciousness briefly, complaining of a really bad headache, then started bleeding from his nose and ears. Then he blacked out again.

They took him to the emergency room at the regional hospital in Santarém. It is one of the most dangerous medical centers on the planet. That night, it didn’t matter. Via text message, the news spread quickly and a small crowd began to gather. He was DOA. Doctors officially listed the cause of death as unknown. He just died.

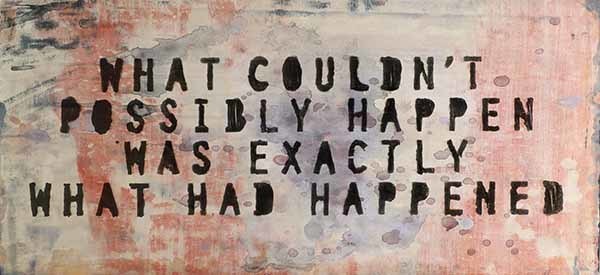

Felipe wept uncontrollably. It was one of those things. What couldn’t possibly happen was exactly what had happened. Felipe had never been very far away from Thiago. I had only ever seen two souls closer when they were identical twins.

Identical twins share the same soul and, for all practical purposes, the same body, though a body capable of going off in two directions if it wants to, though rarely does it ever want to. Felipe and Thiago were like that, conjoined at the heart. They even had the same feast day on the calendar of saints.

The only difference was that Felipe was clearly the older brother, eternally in charge of Thiago. They showed some childhood photos at the funeral. Photos of Felipe watching over his brother, making sure that, in Thiago’s spontaneous innocence, he was OK, making sure he never sank to the bottom of the pool and died. But he did.

When Felipe got to the emergency room, Thiago was already gone. He was naked except for racing trunks and covered with blood, as if he had just been born. Felipe picked him up to hug him and got blood all over him. He got Thiago’s life all over himself. And there it will stay, for the rest of eternity.

Felipe called me from the hospital. I didn’t understand a thing he said. He always spoke too quickly on the phone, and there was a lot of static on the line. This time, though, he was coming apart, saying a million incoherent things all at once. To make matters worse, he had called from Thiago’s cell. I thought it was Thiago saying that their mother had died. But it was Felipe, saying that Thiago had died, filho da mãe.

Thiago had been on a fitness binge. Some days, it would be soccer, then taekwondo, then he would go run with me at the city park. He would overdo it. But all 17-year-olds overdo everything. He didn’t die of that.

I think he had a massive stroke, or perhaps he burst an aneurism in his head. It would have happened, sooner or later. An autopsy was not performed, because the boys’ father got there before their mother, and he was a Jehovah’s Witness. They don’t do autopsies. They assume that the only real cause of death is the wrath of God.

After midnight, they found Thiago’s mom. She was interested in knowing if her dead boy had died of something hereditary that her living boy might also have. But his body was already in the hands of the morticians. She later talked about exhuming the body, but I think that was because she couldn’t let go. I told her the smartest thing would be to have Felipe checked out. At someplace besides the local hospital. They were experts at amputations and sudden deaths, not complex diagnoses.

It was the only time I ever really felt like I wished it had been me. People often say that, but it’s usually not true. What people are secretly thinking, even when a loved one has passed away, is thank God it was you and not me.

Once, when Dad came to visit me in Chile, we had an issue with the water pump at the beach house. He laughingly insisted that he would hold the hot wire to the connection, because he had already lived more years than anyone else there. Yeah, like that. If anyone was going to get electrocuted, run over or struck down by Jehovah’s insatiable wrath, he thought it should be him.

That’s really what I was thinking when Thiago died. But I had no way of taking the aneurism out of Thiago’s head and putting it into mine. Besides, he was already gone.

At memorial services, they always say the deceased was the kindest person, the most loving, everybody’s favorite human being and all that. It’s usually a lie, but Thiago really was all that. He had some unconscious magic qualities, an indescribably prodigious way that made him an endangered species. He didn’t really fit into our miserable world. That was, perhaps, the true cause of death. The underlying cause.

He was so innocent, he had no notion that others didn’t have those same magic qualities. They called him impulsive, but he was intuitive. It was as if he were seeing in colors while everyone else was seeing in black and white. His frequent misunderstandings in everyday life came from his belief that others perceived what he was perceiving. He was just wired differently. Maybe that’s what killed him. His wires got too hot.

The coffin was too small. Perhaps it’s all they had at the funeral parlor on a moment’s notice, or maybe his dad just picked the first one he saw, imagining that his son was still a little boy. It was flimsy, too, made for the weight of a child. The cousins and classmates who carried him in the procession had to put their hands underneath so he wouldn’t fall out the bottom. That sort of thing shouldn’t happen at funerals. If the bottom falls out of the box, you have a body on the sidewalk. Then what do you do?

After it was all over, the parish ladies got together every afternoon for a week to say the rosary for Thiago’s eternal salvation. He was an altar boy, after all. His buddies draped the saintly white tunic over the coffin during the wake. But the parish ladies imagined that because he was young and male — the worst possible combination, in their pious eyes — he had probably accumulated a long list of unthinkable sins. They professed that dusty self-righteous piety that passes for religion the world over.

There was some anxiety on their part because, on the day of the burial, it got late and they didn’t say the rosary. In Brazil, the tradition is seven days of rosaries, rigorously recited without skipping the verse about the fires of hell, and a Mass for the eternal repose of the soul of the faithfully departed on the seventh day. It had to be exactly right. Like medieval sorcery, it was supposed to keep dead sinners out of Lucifer’s corral. It’s all most people really believe in, or even understand, about salvation. The parish ladies were convinced that Thiago would be excluded from the circle of divine love for all eternity because of a glitch in the protocol.

Felipe’s grief took a long time. He wore his brother’s favorite shirt till it was threadbare. To this day, he uses Thiago’s cell phone. Felipe made a baby with his girlfriend not long ago. It’s going to be a boy. He hasn’t been born yet, but his name is Thiago.

Perhaps he will inherit his lost uncle’s special magic.

Nathan Stone, a member of the Chilean province of the Society of Jesus, was ordained to the priesthood in 2000 and has worked in education, youth and social action ministry in Santiago and Antofagasta, Chile, and Montevideo, Uruguay. At home in his native Texas, he is on sabbatical from his work in the Amazon region of Brazil while he cares for an ailing relative.