I teeter as the river’s frigid water swirls around my legs. Treading across a freezing mountain stream in Lesotho, southern Africa, the stinging pains that shock my bare skin fade into a throbbing numbness. With one slippery misstep, my traveling partner, Amy, crashes into the water, shrieking as she scrambles up, soaking. Our tiny Basotho companion, Nthabeleng, having effortlessly darted across the water, watches us from the bank, entertained by our antics. As we stumble toward her, a pack of men on horses ramble down the dusty path and through the water, heading into town.

Several hours and some very tired legs later, we reach a village perched impossibly high on the mountain to visit a young boy and his grandmother. Months ago, Mathathene would have lain, wasting, in a dark corner of his home; today, he dances outside with one foot in an old leather shoe. The healthy, giggling boy lives because of the outreach project of the Touching Tiny Lives safe house for HIV/AIDS-impacted children, my home in Lesotho this summer.

After weighing Mathathene, delivering medicine and canned food, and catching up on family news, Nthabeleng, Amy and I head back down the mountain and once again reach the dreaded river. As I tread back through the numbing waters, the same group of men rides over the embankment, startling me. I shield my eyes to watch them against the sunlight; in the silhouette I see large boxes being held against the horses’ backs. For a flash I think they have purchased electronics at the hardware store. They cut the sun. Oh, wait, coffins.

Nthabeleng throws herself on the dusty ground as the horses with their coffins stomp toward us. The brilliantly polished boxes look to be the work of Peter, one of many carpenters-turned-coffin-makers in town. Nowadays it is the only business making a profit in Lesotho’s desolate mountains. Tiny coffins for babies, little coffins for children, big coffins for mothers and fathers. HIV/AIDS has turned Lesotho’s economy into an economy of death.

Amy and I exchange panicked looks—should we prostrate ourselves like Nthabeleng? Say something? Weep? Pray? Instead, I stand, now frozen to the scene, as a heavy, devastating numbness turns my breathing shallow. I eye the horses as they splash alongside me and tread up the dry path toward the village I am returning from. I stand in a stream in southern Africa, half the world away from my home, and watch HIV/AIDS’ economy of death proliferate.

As time passes, I do not want the reality of a pandemic to freeze me in that river. The facts, the figures, the horrifying nature of HIV/AIDS have frozen our response for far too long—how do we not go numb? How do we not despair?

I do not have the answers to solve a pandemic. I do know that there is something profoundly wrong with tiny baby coffins. We will not keep babies from those coffins unless we awaken to HIV/AIDS’ wrath in our world and realize our capacity for action—to cross those painful rivers, climb into those villages and offer up whatever we have to touch tiny lives.

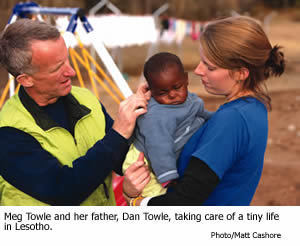

Meg Towle will graduate from Notre Dame 2007 in May with a degree in anthropology and an international peace studies minor. Named a 2007 Marshall Scholar, she will begin graduate studies in international health management next fall in the United Kingdom. To learn more about the work of Touching Tiny Lives in Lesotho and the United States, visit the Touching Tiny Lives website.