We were close to the summit on Naya Kanga, a 19,000-foot mountain in the Langtang region of Nepal. It was late afternoon and the sky was turning dark blue. A cold north wind was blowing off the Tibetan plateau. I was tired and anxious to get down.

At that moment I was roped to my friend Nanu Thapa, an experienced Himalayan climber, descending slowly on a snow-covered slope so steep we had to face into the mountain as we climbed down. I moved carefully, one foot at a time, using my ice ax and the toe points on my crampons for support. There was nothing to stop a fall for a thousand feet.

Pushing my ice ax into the snow, I fixed my rope around it and planted my toe points as firmly as I could. I watched Nanu unrope above me. He would climb down and leapfrog to a point below me, a pattern we would have to repeat many times before reaching the safety of the ridge that led to our tents.

But this time, just as Nanu pulled his ice ax from the snow, his crampons failed. With no warning, he fell off the mountain, out into space, tethered to me by our climbing rope.

Try, try again

I was not an experienced climber. I had used crampons only once before, 10 years earlier on a failed attempt to climb the Matterhorn, part of a midlife-crisis adventure when I turned 40.

I was 50 now and working in Nepal as part of the U.S economic assistance program (USAID). Not having learned my lesson in Switzerland 10 years earlier, I had happily joined three colleagues in planning an ascent of Naya Kanga, the 15th highest trekking peak in Nepal — and 5,000 feet higher than the Matterhorn. It is one of the few trekking peaks in Nepal accessible to fit but not technically trained climbers.

In addition to Nanu, our climbing team included Todd, the political officer at the U.S. embassy; John, the embassy doctor; and Tom, with whom I worked at USAID. They were each extraordinarily fit. John also was a technically qualified climber, having summited a number of difficult peaks. I was the oldest, but I had trained hard and was confident, unjustifiably so as it turned out, endurance would not be a problem.

Todd’s girlfriend and future wife, Julia, was also with us. She was in Nepal working on her doctoral dissertation, and was also in terrific shape. She carried the same heavy pack as the rest of us, but never planned to climb higher than base camp.

To summit Naya Kanga we had to overcome two logistical problems. The first was to reach Ganja La pass, where we would find a ridge leading to the couloir from where we could climb to the summit. The second was to acclimatize to the altitude once we got above 10,000 feet.

The rule is to “climb high but sleep low.” Above 10,000 to 11,500 feet it is safest to camp no more than 1,000 feet higher than you slept the night before. With this in mind, we took a jeep from Kathmandu to the hamlet of Sundarijal, at the end of a dirt track, and started our hike at about 4,500 feet. We reached the Ganja La pass, at an altitude of 16,000 feet, after an easy ascent over five days. The only technical section of this part of the trip was getting through the pass itself, where we had to inch our way across a narrow, snow-covered ledge in the rock face of the pass, with a 40-foot vertical drop below us.

Once across the pass we had a short climb to a protected clearing among some rocks where we set up our camp in the snow. It was almost dark by the time we got our tents up, and since it was too cold to be outside once the sun went down, we quickly made our supper and got into our sleeping bags. We had to get an early start the next morning to avoid climbing in the heat of the day, when the intense rays of the sun can turn the snow to mush.

Out of the tents at dawn, we put on our crampons and cold weather gear, carrying light packs with only the water and food we would need for the summit push. Before starting out, John demonstrated how to use an ice ax in case of a fall, making each of us fall on the snow and slam in our ax as if arresting a fall on a steeper slope. It was not an auspicious way to start, but we treated it lightly.

The wrong way

None of us had been on Naya Kanga before, including Nanu, our guide. We had a general description of the route, but only a poor photo of the actual mountain. As a result, we picked the wrong way up. Our route was directly in the sun all day. It soon got so hot we were climbing in our thermal undershirts, and the snow on the steep slope became heavy, wet and difficult to navigate. For a while I took an adjacent ridgeline, above the couloir, but that was even worse.

Climbing several thousand feet in those conditions was hard on all of us, but I don’t think I realized how fatigued I was. When we finally reached a plateau, a mere hundred vertical feet below the summit, we stopped briefly to rest. But we were well behind schedule so couldn’t stop for long.

When the others got up to complete the climb to the top as the wind blew hard, I found I couldn’t go on. I yelled up to Tom, asking him to come back to help me tighten my crampons. I couldn’t seem to reach them in my bulky clothes — and my body, not very limber to begin with, had stiffened during our short rest. Disregarding his own anticipation at reaching the summit, now only steps away, he generously returned to help me.

As Tom worked on my crampons, I became obsessed with the desire to get off that mountain. I was suddenly as scared as I had ever been in my life. I demanded that Nanu take me down, insisting, for added safety, that we be roped together.

Almost two decades later, I still find it hard to come to grips with that moment. Up until then I had felt no fear on Naya Kanga, and I was in absolutely no danger sitting where I was. But fear consumed me. I could think of nothing but my own safety. I read recently that experienced climbers call that kind of collapse “crumping.”

I have never been able to rationalize why I panicked, much less how I justified appropriating our guide for my own safety. I can only imagine that I was extraordinarily tired, and what had been up until then a sunny, pleasant day was turning dark and ominous. The strong wind near the top added to my sense of foreboding.

Tom recently told me that when he turned back to help me with my crampons, and looked down the slope we had come up, he felt an imminent sense of disaster. Peering down into the Langtang Valley, at least 10,000 feet below us, he remembers seeing a helicopter flying eastward and feeling certain that unless we found the correct route down one or more of us would fall to his death. He too forgot about the summit and started focusing on finding the correct route down.

Todd and John, who had continued on towards the summit, must have been confused by what was happening, but they didn’t object when we started going down without them. Nanu, a gentle soul with muscles of steel and as limber as a cat, clearly understood my fear. He didn’t object to abandoning his own climb to help me down. I felt an enormous sense of relief as we roped up, leaving the others to enjoy the summit before they would have to hurry down to beat the sunset.

My sense of relief was short-lived.

What I didn’t know when we started down was that Nanu was wearing Todd’s crampons, which Todd had rented in the Kathmandu bazaar. They were half split through in places and would not stay secure. When Todd had showed them to Nanu earlier during the climb, Nanu had insisted on giving Todd his own German-made crampons, and thus was wearing Todd’s defective crampons on our descent.

Soon after we started down and got out of the wind, I regained my composure. I felt fine, normal. Several minutes later, when we were out of sight of the others, we discovered the correct route we should have taken to the top. It was the couloir adjacent to the one we had climbed, with the ridge that separated them keeping the proper route in the shade during most of the afternoon, which would have made for easier climbing.

There was no way to tell the others what we were doing, but we assumed they would see our tracks in the snow and realize we had found the correct route and follow us down. It was about 20 minutes later when Nanu’s defective crampons failed, and he fell off the mountain.

Fate at work

I wish I could say what happened next was a result of mountaineering skill. It wasn’t. When I saw Nanu fall, I closed my eyes and wrapped my arms as tightly as I could around my ice ax. Nanu didn’t make a sound as he fell. Miraculously, he didn’t hit me on the way down. When he reached the end of the rope (about 30 feet), it was with a jolt that pulled my crampons at least a foot down the slope. Somehow the shock of his weight at the end of the rope didn’t pull me off the mountain.

I opened my eyes and looked down. Nanu was hanging upside down, dangling from the rope. He quickly righted himself, dug his boots into the slope and planted his ax, which had been tied to his wrist during the fall. We both caught our breath, and then he yelled up to me that his crampons were completely broken and he couldn’t climb farther without them.

There was a rock outcropping on a ridge about 40 feet from us. Very carefully, we worked our way laterally to it. When we got to the safety of the rocks, and after we unroped and waited for our hearts to stop pounding, we realized we were still in a jam. Nanu couldn’t climb without crampons, and I didn’t have the skill to belay him on the single rope we had. If our friends failed to see our tracks, and descended on the original route we had climbed up, we would be stranded.

You can survive a night exposed at 18,000 feet, but we didn’t want to try. We both began yelling up the mountain, hoping to attract attention. It was pretty hopeless as the wind was against us. We spent a few glum moments as the sky continued to darken, but very shortly we heard voices. Our companions had seen our tracks and followed us down the new route.

As soon as they reached us, John, the experienced climber, started rigging ropes to belay Nanu down the rest of the way. We followed. By that time I was happy not to be roped to anyone. I took my time and arrived at the bottom just as it was getting dark, exhausted but happy. Walking across the ridge back to the tents, I heard Todd ask John, “What happened to Kelly at the top?”

I didn’t hear John’s answer, and it was never mentioned again, but I have often thought about that moment. I was chagrined to have lost my nerve, especially in front of my friends. I knew I had been overcome by something irrational, and assumed physical exhaustion had contributed to it, but that didn’t make me feel much better. The only thing helping my battered self-respect was that somehow I had been able to stop Nanu’s fall.

The more I thought about it the more I started to believe fate must have been involved in that climb. If I hadn’t asked Nanu to help me down, we would have descended as a group, and most likely been unroped, as that is how we had ascended. Nanu’s borrowed crampons still would have failed, but no one would have stopped his fall.

Nanu must have felt the same way, for soon after we got back to Kathmandu he presented me with a new pair of German-made crampons. I didn’t want to accept them as I knew how expensive they were, and that he really couldn’t afford it, but he insisted. I had saved his life, he said, and giving me a gift in return was important to him. According to his religious beliefs, he now had a responsibility for my life.

He also told me that when he fell off the mountain he knew he was going to die and had only one thought while he was falling: He felt humiliated knowing he was about to pull me, his client, off the mountain. His responsibility as a Sherpa was to protect me, and he had failed.

I wanted to tell him, but didn’t because it would have sounded as ridiculous as it was true, that I was the one who should have been thanking him. By falling off the mountain, Nanu gave me a chance, unconscious as my actions were, to save him. He had allowed me to redeem my seriously flagging sense of self-esteem.

Nanu was an inspiring guy, good-natured, with an almost spiritual calm under stress. He was careful and skilled at his work, and was always smiling and doing more than his share. I have thought about Nanu’s kindness on Naya Kanga over the years, not only because that moment was important to me, but also because it was not the end of our friendship.

The morning after our climb, as pre-arranged, Tom and I left on a 10-hour hike to Dhunche, a trailhead where a jeep would be waiting to take us back to Kathmandu. Todd, John and Nanu stayed on to hike out via a little known route first explored by English Himalayan explorer H.W. Tilman in the 1950s. Rather than return to Kathmandu with us, Julia decided to spend a few days at a tea house in the Langtang valley.

I remember telling my colleagues when I got back to the office that high altitude climbing was not an activity to take up in your 50s. When Todd, John and Nanu returned a week later, having bushwhacked a trail even more arduous than they had anticipated, they looked like they had aged a decade.

A final farewell

At that point I was sure I would never again set foot on a high mountain, at least not in crampons. But time passes and one forgets. The pull of adventure takes over. Just a few short months after our November 1991 climb, Tom and I began planning another trip with Nanu, this time to a mountain over 20,000 feet, called Mera Peak.

As the time for the climb approached, Nanu asked that we meet him at Namche Bazaar, a Sherpa village at the beginning of the trek to Mount Everest. He would be leaving Kathmandu before us to participate with other Nepalese climbers in an ascent of Everest, or Sagarmatha as the Sherpa in Nepal call it (“Chomolungma” in Tibet) — in both cases meaning something like “goddess mother of the world.”

There is something about Mount Everest that makes climbers take extraordinary risks. People have skied down it, paraglided off it; someone even rode a kayak down on the snow until reaching the water coming out of the Khumbu glacier. There is even an annual Everest marathon, from base camp down to Namche Bazaar.

In Nanu’s case, his team was trying to break the speed record for the fastest ascent. A Frenchman then held the record, having climbed from base camp to the summit and back in a little under 24 hours. Nanu would be stationed at the South Col, at about 26,000 feet, with oxygen and hot drinks for the principal Nepali climber as he passed by.

Sherpa guides often have been given secondary roles when it comes to sharing the glory of an Everest summit, so this all-Nepali expedition aroused a great deal of pride in the Sherpa community. When Nanu and his teammates passed through the small villages on the way to Everest base camp, while carrying extraordinarily heavy loads, the local populace lined the route offering drinks of the local, potent liquor to toast to their success.

Nanu made the journey from the Lukla airport, at 9,100 feet, to the Everest base camp, at over 17,000 feet, in one day. Trekkers normally take six or more. He had to be extraordinarily strong to do that with such a heavy load, but he was tempting fate to climb so high in one day without acclimatizing. Perhaps the alcohol clouded his judgment.

Later that night he began to show symptoms of cerebral edema. Leaving his tent in extreme pain, he wandered around base camp looking for help. For some reason, perhaps because they were also feeling the effects of alcohol, his fellow Sherpa failed to assist him. A foreign climber with another climbing team realized how sick he was and arranged to have him carried down in the dark to Lobuche, where a volunteer high-altitude doctor had a depressurizing tent.

The volunteers who carried him down managed to get him into the tent while he was still alive, but it was too late. He died before the tent could reduce the pressure on his brain. The next day his compatriots cremated his body on the mountain.

Tom and I were obviously shocked when we heard. We had been scheduled to join Nanu in only a few more days. We immediately canceled our climbing trip but decided to travel to the Everest region and find the spot where Nanu died and pay our respects. We carried with us a plaque Tom had made in Kathmandu honoring Nanu’s memory.

When we reached Lobuche, after flying into the small mountain airport at Lukla and hiking in via Namche Bazaar, we found the high-altitude clinic, but the doctor was absent. We never did get a chance to ask him what exactly happened that night. We stayed in a Sherpa hostel next to the stone hut where Nanu died. The proprietor allowed us to hang Nanu’s plaque on the wall.

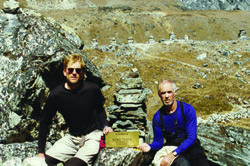

Earlier we had climbed to the spot where rock cairns (chortens) have been erected over the decades to honor the many foreigners and Sherpa who have died trying to climb Everest. We built one for Nanu.

It was important for Tom and me to honor Nanu’s memory. He was our friend. And one afternoon on a minor mountain in Nepal, Nanu had taught me an important lesson: You may not always have the strength to live up to your own expectations, but fate can give you strength when you need it most.

Before his retirement in 2003, Kelly Kammerer was a public service lawyer and civil servant/foreign service officer working on economic assistance issues. He and his wife now live on a farm in Provence, where they produce “a fair olive oil and a barely drinkable wine.”