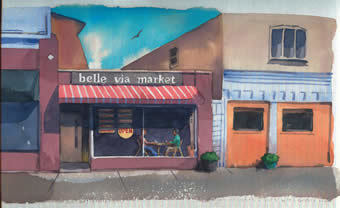

I have good reason not to be here. I should be at work, or at least on my way back to work. But here I am at the Belle Via Market and Café in tiny Three Oaks, Michigan. It’s a little health food joint on Elm Street, the main drag through town. The proprietor, Jane Pellouchoud, assembled a garden in a pita for our lunch, involving homemade hummus, cucumbers and sprouts and a bright orange carrot-juice smoothie that I’m still sipping post-lunch.

Jane and my lunch partner, Andy Burd, a 1962 Notre Dame graduate, are over by the window. We’re the only ones here. Cheery sunlight filters through the storefront window, casting a pleasant shadow over the pair. Andy has his banjo, Jane her guitar. I am leaning back in my creaky wooden chair, watching and listening. Andy and Jane are tuning their instruments.

Out the window an occasional pickup glides by, a pedestrian strolls along the village sidewalk. Outside the light is golden, the sky a radiant blue. Tree limbs, still flush with autumn’s bold reds and yellows, sway in the wind. A block away there is a schoolyard full of hatless, winter-coated children darting, racing, chasing, and hurling armfuls of crackly auburn leaves. I could sit here all afternoon.

Andy and Jane are rehearsing. It’s not a polished act. The music and lyrics are spread on the table between them. It’s past 1 p.m., and I am 30, maybe 45 minutes from my office. But I am here, and in no hurry to get back there. My rationale? It just feels right to sit here in the Belle Via Café on Elm Street in Three Oaks, to stop, take a timeout and listen to folks of a mind to pick and sing in the middle of the day, where raggedy pickups course through town at 15 mph and the school bell calls small-town kids off the playground, shuffling and shoving back through narrow doorways. October yards are full of dry leaves and jack-o’lanterns, cardboard tombstones and bedsheet ghosts, a wisp of All Souls’ Day and a whiff of impending winter.

Andy is a filmmaker who now lives in New Buffalo in a house up the hill from the Lake Michigan beach. He’s been self-employed most of his life, doing creative work for clients like Notre Dame and John Deere, Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, and a band of missionaries in Haiti. He and I had corresponded sporadically for years, finding kinship in our work, some shared ways of looking at things. So I sought him out several years ago when I was looking for a lift. I sought him out again this week, needing a lift. We agreed to meet for lunch halfway between the lake and South Bend. I wasn’t expecting the concert, but it wasn’t a total surprise.

Andy, honing in on 70, had gotten serious about playing his banjo, and he’s taken to performing at the open mic sessions on Tuesday nights at the Acorn Theater, a block away from here. He and our luncheon hostess are practicing their duet for tonight’s show. I am grinning at the two old-timers living life. Andy sings twangy like an old Oklahoma country boy, which he is. Jane is ponytailed and frail, shy and lissome as a crane. I’ve pegged her as an old-time hippie with the beauty of a lifetime etched into the creases in her skin. When she sings, she shuts her eyes and goes away and rocks her head from side to side, purr of a smile upon her face. I love it.

Grace

There was a time, when I was younger, when I thought a tableau like this profound, even holy. I am less prone to flight these days. I am 57 now, and fine, simply, to be in the company of such good-hearted souls. I do believe in the grace that comes in moments like this, and think such times are reasons for living. That’s why I’m here.

It has occurred to me that in recent years I have unconsciously gravitated toward friendships with those older than me. I’m not sure why. But for lunches and coffee I have sought those who have gone before me as scouts, or as if the sages of the clan. It’s funny. When I was younger, I had things so figured out that I was not drawn to those wiser than me. I had my answers.

Something has changed, though. My questions have gotten taller, the unseen answers float higher. It’s as if the scope of my wondering now reaches above the star-domed sky. I’m still trying to learn how to live, looking to those up the road a ways, not necessarily for words of advice, but to see what they hold on to, the things that matter — how to be. Even things like throwing yourself, late in life, into banjo-picking.

My father died last year. I could count on one hand the rock-solid things he said to guide me on my way, to get me through life. But his life and his ways are so woven into me that I marvel and smile at his presence in my days. He shapes me in ways I’ll never comprehend. I have two grown sons, each about to get married this spring. At home are three 5-year-olds, a litter of rambunctious joy, and a strong, sweet blessing of a wife. My mother, who is almost 90, says one of the few things good about getting old is that you’ve been around long enough to see how things turn out. Sometimes it feels like I’ve had two or three lives, so disparate are its chapters. And sometimes, appraising my life, wondering what I’m doing here, what’s it mean, what’s it all for, I sit comfortably in the mystery, letting the music play.

The finale of the Andy and Jane gig on this night will be a duet they’ve patched together combining a Hank Williams classic, “The Wild Side of Life,” with its famous line, “I didn’t know God made honky tonk angels,” and a country chart-topper Kitty Wells composed in response: “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels.” The resulting medley that Andy and Jane are practicing now — rough, loose yet somehow ripe with feeling — is a spirited male-female dialogue of unfaithful love, heartache and blame for which they’ve written their own ending. “Take my love and shove it up your heart, dear,” Andy croons, before turning it over to Jane, whose final verse is sung with such real and vulnerable sadness that you can imagine the private cinema playing behind her closed eyes.

“When I think of the times we’ve shared together,

Your smile and the warmth of your embrace,

Let us feel the grace of forgiveness,

And forget the mem’ry of disgrace.”

Reality

My life is divided into parts largely because some years ago I decided I did not like where I was and did not want to continue along that river. I was old enough to fully grasp what it means to have but one life to live — one shot at this existence only — and I wanted better, painful as it was to turn so abruptly. Most times, I think, you steer your life to sense and ride the flow. But sometimes you just have to stand up for yourself or some belief and fight against the currents. I have been on the other side of that fight long enough now to taste redemption, to be grateful for the gifts of life.

In happy times and sorrowful ones, I have come to understand that my own life’s narrative is nothing more than the living of a life. And much of what I’ve encountered is simply the happening of that life, all the things that life does to you, saddles you with, offers you. Nothing too remarkable, too extraordinary. How many times lately have I concluded, “That’s life. It’s just life.” And sometimes, seeing another’s tragedy or misfortune, I’ve thought how devastating for that to happen — because of what it means and does to their one and only life.

We all know what a miracle life is, from galaxies to DNA, and we rejoice in creation’s beauty and genius, its poetry and music. Life is precious, tenuous and fragile. But we also know it can be unfair and cruel, arbitrary and impersonal. And, as the old saying goes, “There’s no way out alive.” It’s life’s very meanness that makes me dislike people who make life harder for those around them. Life is hard enough. We’re all here together trying to make sense of it all, doing the best we can, getting through the burdens and the best of days. Why make it worse, why make it harder and meaner for those around you? In fact, it might be a worthy enough life goal just to make life a little better for those around you. That’s probably enough to shoot for.

I like the phrase, “generosity of spirit.” A colleague told me recently of a definition he liked: “Generosity means being someone else’s good luck.” I do think we’re happiest when acting as an instrument for good or God, for humanity or the earth or some truth or higher power, a higher calling that brings meaning to our meager selves. How limiting and small any alternative.

But it’s hard, too, to keep your bearings in the barrage of life. Life has a knack for unmooring us from what really matters. Then again, it’s often life’s sledgehammer fist that gets our attention again, that comes along to show us what matters most. I guess I’ve come to that stretch in life where I’m taking stock of what endures and what doesn’t, what has lasting value and what to seek in the time remaining.

The Belle Via concert-for-one is on its final chords when a customer walks in, walks past Andy and Jane, peruses the store shelves stocked with all manner of health food. A fit-looking gray-haired man, he browses and ignores the troubadours. But now with a larger audience, Andy isn’t done. He plays on, fingers twiddling on his banjo strings, a familiar melody I can’t quite place. But the lyrics are his; he’s making them up as he goes, encouraging this new customer to purchase Jane’s wares — food to make him feel better, live longer.

A few weeks ago a colleague of mine and I were talking about his career goals, and, at age 36 and with a wife and five kids, he said he still wasn’t sure what he wanted to be “when I grow up.” He asked if I had figured that out yet, and it occurred to me, for the very first time, that I had passed that sentiment by. It has already happened. I have already grown up.

This discomfiting realization reminded me of a sweet scene in a movie I saw recently, a French film called Avenue Montaigne. An older man, an art collector, is explaining some things to his somewhat distant son, and he says that he has come to that point in his life when he has stopped thinking about the passing years — to now be focused on the remaining years.

Andy strolls about as he continues his improvised serenade until he runs out of rhymes and rejoins me at my table. Time for me to move on.

Andy and I walk over to the counter to settle up, visit a bit with Jane before I leave. The customer has placed some items on the counter for purchase, and the conversation turns to my being here, the refreshing reprieve from my work-day life, the need to get back. “There’s some stuff back there I needed to step out of, and it feels good to get out of the city to be here awhile in a little town,” I say, adding, “Not that South Bend is that big of a city.”

“But it’s got entanglements,” the customer says. “Anywhere you live has its entanglements.”

He and I exit the shop together. He carries his brown paper bag of health food down the street. I climb into my car and head south out of the Michigan countryside, back into Indiana, back toward those entanglements. I know, when I get back to the office, that I’ll find everything there pretty much the same. But it’ll look different and I’ll feel different because of my field trip today. I’m getting some things straight in my head, some things about life. A little distance brings a nice perspective.

A trade-off

I keep mulling over that word entanglements, and I know exactly what the guy means. The tyranny of responsibilities, obligations, demands, expectations, voices calling in the night. Sometimes life feels like a vine that’s wrapped too tightly around you, squeezing. Or a hailstorm of burdens, too many boxes to carry, a room with the clutter and walls closing in. You want to break free.

But here’s the irony: All those entanglements, those boxes, those burdens are the people and jobs, the communities and commitments we’re most invested in. And in one of life’s typical, head-scratching paradoxes, those investments are the very engagements that bring us meaning and fulfillment, gratification and purpose, love and respect. Weird how that works. Trickster God.

About 15 years ago now, about the time I crossed the Continental Divide of my life, I realized that everything in life is a trade-off. You go here, you can’t go there. You choose this, you can’t have that. You get these freedoms, you get those responsibilities. You decide to do this, you take on all that comes with it. Everything we do has its goods and bads. That’s life. It’s good to be invested, but giving oneself has its pains. Anyone who has loved, anyone who has had children knows this.

I became a father 31 years ago. It transformed my life, indescribably. My life’s meaning and purpose, my understanding of family, the unfathomable rope of countless generations, the meteoric awe of a single life — all transformed. Decades later, when my sons were grown and I had remarried and we prepared for the arrival of triplets, I told my wife that children would bring wondrous, inexpressible joy; they would also bring heartache.

I’ve been thinking a lot about life lately. I’m not sure why. I keep thinking about it, driving back to work after my brief respite in Three Oaks, making a case in my head for enjoyment, for laughter and moments of idle charm. But my thoughts land, too, on a particular moment, a moment that sharpens my thoughts on life to a single image.

We are in an examining room. It is six years ago and Jessica is in the fifth month of her pregnancy. We are looking at the ultrasound while the doctor, a specialist in high-risk pregnancies, is pointing to the screen. One of the triplets is fine, riding high in the womb, in her own placenta. But these two here, he says, share a placenta, because very early in the pregnancy an embryo divided to form these identical twins. And sometimes, he explains, we get a condition called Twin to Twin Transfusion Syndrome, because they don’t share the placenta equally. In fact, the so-called “donor twin” forfeits necessary nutrients to “the recipient.”

Jessica and I look at the screen, we look at each other, bracing for bad news, wanting to know what it all means. Despite sharing the placenta, the doctor continues, each twin is in his own sac, which he outlines on the screen as a chalky line surrounding each fetus. The donor twin, we learn, eventually responds by partially shutting down the blood supply to many of his organs, especially the kidneys. Reduced urine output means very little amniotic fluid, and a sac collapsing like shrink-wrap around him. “It’s like a balloon,” the doctor says, “that’s compressing around him.” Further tightening, he says, could prove devastating.

The recipient, on the other hand, produces excessive amounts of urine and is immersed in a large amount of amniotic fluid. He is curled comfortably in a roomy bubble, and I assume he’s doing fine. But the news gets worse. The abundance is too much. The recipient’s blood becomes thick and difficult to pump. The result is heart failure and death.

And because of the blood vessel connections across the placenta, if one dies, both die.

In fact, it’s unlikely the third fetus will survive.

Death occurs in 70 to 80 percent of the cases; survivors may have injuries to their brains, hearts and kidneys.

Finding peace

Each statement brings its own sledgehammer blow. Shock waves shiver though me. I can’t speak. The doctor continues. Surgery options mean hospitals in Milwaukee, Philadelphia; he can call for us. My wife and I look to each other, then the doctor adds, “There’s another procedure we can try. It’s sometimes successful. What we do is drain fluid from the recipient’s sac, the bigger sac. We might have to do it two or three times. Sometimes, doing this, the fluids equal out, eventually might find equilibrium. Sometimes it works.”

The medical literature says survival rates with this treatment approach 60 percent — “although it is not known exactly how amnioreduction improves the state of both twins.” This isn’t an especially encouraging testimonial, but the doctor seems reassuring, confident. So we nod and say okay, but then I am startled by the rudimentary nature of the procedure.

The doctor gets a big, long needle. He gets a clear glass bottle off a shelf and a rubber tube from a drawer and a little rubber connector to fasten the needle to the tube which he slips loose into the bottle. He then inserts the needle right into Jessica’s stomach, eliciting a squirm. The needle appears on the screen. It is fishing in the recipient twin’s sac.

And immediately a semi-clear fluid starts moving through the tube and drains right into the glass bottle. Astoundingly simple this homemade remedy for such a complex threat to life.

I hold Jessica’s hand and watch the screen. I can see the boy in the bubble moving, tiny and alien-looking and blurry as he is. I make out his hand and I watch as that hand moves. I watch the hand as it moves eerily toward the needle, and I see it grasp the needle’s tip, close its tiny fingers onto this needle that has entered his dark, heart-pulsing, liquidy belly of a world.

And as the hand grabs the needle, the fluid stops, there is no flow.

The doctor and I look at each other. He chuckles and says, “Come on now, let go,” and he jiggles the needle, moves it around as Jessica winces. And the boy lets go. And the fluid flows once more, emptying into the bottle.

Hello in there.

It wasn’t the only time that little hand grasped the end of the needle, stopping the flow. The procedure was repeated on two or three subsequent visits. Throughout those weeks I prayed like I had never prayed before.

Jessica and the triplets made it to 30 weeks this way, until one Friday morning the doctors said it was time to get everybody out or we’d risk losing them all. They were delivered later that day. And even though they ranged in weight from 2-pounds, 6-ounces to 3-pounds, 3-ounces, and had some issues early on, they are today healthy and happy and as normal as can be.

But I know how life works, how very quickly it all can change. So I feel nothing but gratitude for all that life has brought my way, and I try to remember it daily. I try to let go of regrets, find peace in forgiveness. I have thought a lot about life lately. I’ve thought a lot about my father. I’ve thought about my mother living alone in Louisiana, and my own grown sons well on their way, the love and continuity of succeeding generations and the whole, rich cloth that is the human race.

And when I am mulling things and wondering what it all means — or when I am weary and wanting some solitude or rest, or when the kids are asking for a playmate or help with some unpleasant chore — I see that little hand, that phantom space-invader on the ultrasound, that little bud of life reaching, touching, grasping that oddly intrusive needle that will save his life, and his brother’s and his sister’s. And his mother’s. And mine.

Kerry Temple is editor of Notre Dame Magazine.

Drawing by Terry Lacy.