Peter Yoches needs all the patience he can muster this morning. It’s a little after 8, and his class is slow in settling down. No wonder: It’s Thursday, and in three hours these eighth graders will begin a three-day weekend to celebrate Flag Day, a Haitian holiday. They’d prefer to begin it right now.

Technically, Flag Day was yesterday, but rather than break the school week in the middle, Louverture Cleary School will take tomorrow off. Today’s class schedule has been shortened so some students and staff can attend a wake for a classmate who, a few days ago, had the bad luck to step off a bus into the middle of a gun battle in a dangerous section of Port au Prince.

This private, Catholic, secondary school on the outskirts of Haiti’s capital city is a walled island of safety in a city where murder, kidnapping and gun battles are rampant. The immediate neighborhood, known as Santo 5, is a study in contrasts, with a few upscale homes occupied by professionals or government employees next to a squatters’ village of small mud and metal huts with no electricity, running water or sanitary facilities, largely occupied by single mothers and the children they can’t afford to send to school.

Although Santo 5 is one of the safer areas of Port au Prince, violence can occur anywhere, and the Louverture Cleary campus is enclosed by 10-foot concrete walls and locked metal gates that can be opened only by guards on the inside. The school grounds are green, shady and well-tended, with a half-dozen buildings that contain student dorms, living quarters for the volunteers, classrooms, a chapel and a library. All the buildings are clean and painted, with exterior stairways and open doorways and windows—temperatures in Haiti’s lowlands hover in the 90s much of the year, and air conditioning is a luxury found only in a few downtown businesses. When they’re not in the classroom or doing chores, students flock to the basketball court or the soccer field.

Peter Yoches has been a volunteer teacher at Louverture Cleary since he graduated from Notre Dame in 2004 with a double degree in mechanical engineering and French. He teaches English (in English) and science lab (in French). By the time students at Louverture Cleary finish school, they have to be literate in four languages: French and Creole, the dominant tongues in Haiti, plus English and Spanish.

Yoches quiets this morning’s class by starting to read aloud from a book called Paul and Sebastian. A cautionary tale about prejudice, the story begins: “Paul’s mother lives in a green trailer with blue curtains. Sebastian’s mother lives in a blue trailer with green curtains.” Because the mothers despise each other’s lifestyles, they forbid the boys to play together. But the boys become friends anyway, and when the mothers finally accept the friendship there is a ripple of approval in the classroom.

As he reads, Yoches paces back and forth across the front of the classroom, pausing occasionally to make sure the students are following the story: “Does everyone know what obedience means?” “Obeissance” one boy shouts back in French. When the story ends, Yoches assigns homework: First the students have to think up a plot, setting and characters for a new story; then they’ll have to write the story. “Our own story?” asks a girl at one of the double desks, making sure. “Yes, your own story,” Yoches replies.

At last the bell rings and the students troop to the door. Heading for their next classes, they ignore the whap-whap-whap of a United Nations helicopter passing overhead. Like the school’s locked gates and sturdy walls, U.N. patrols are part of the fabric of these children’s lives, not worth glancing up at.

***

U.N. peacekeepers have been patrolling Port au Prince by air and ground since March 2004, after President Jean-Bertrand Aristide fled to South Africa as armed mobs spread violence through the city and the countryside. U.S. Marines came in first to restore order, followed by a Brazilian-led international U.N. force.

Government turnovers are no novelty in Haiti, whose civil history is rife with dictators, coups and violence. Haiti is the poorest country in the hemisphere and a major transshipment point for cocaine headed for the United States and Europe. Its annual per capita income is less than $500, and much of that is money sent back by Haitian expatriates. Eighty percent of the population lives in abject poverty, inflation is rampant, and there is virtually no middle class to provide a measure of stability.

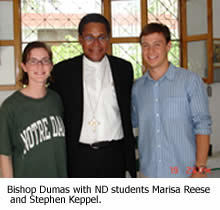

That’s where Louverture Cleary School comes in. The tuition-free boarding school is attended by 350 bright Haitian children who, it is hoped, will go on to college and then into jobs and ultimately, perhaps, start businesses that will help reduce the country’s unemployment. The school is supported by the Haitian Project, Inc., a Catholic mission founded nearly 25 years ago in Providence, Rhode Island, to provide humanitarian aid in the Caribbean nation. The Haitian Project’s key officers are its president, Patrick Moynihan, and its vice president for operations, Marisa (Reese) Jarret. Moynihan lives in Rockford, Illinois, when he and his family are not staying in Haiti. Jarret is a 2001 Notre Dame alumna and former volunteer teacher at Louverture Cleary who now staffs the project’s headquarters in Providence.

During the 2004-05 academic year, two Notre Dame graduates were volunteers at Louverture Cleary. Peter Yoches was one. Stephen Keppel ‘03 was the other. They were the latest in a series of alumni who learned of the Haitian project through Notre Dame’s Center for Social Concerns and signed on for a year or two of service. Some, like Reese Jarret and an earlier ND volunteer, Kate Kowalski ’99, continued working for the Haitian Project back home after their volunteer time was up. Domers were amused this year to learn that one of their fellow volunteers, a graduate of Princeton, first encountered the Haitian Project on the Center for Social Concerns website.

Yoches visited Haiti in his junior year when he was in an engineering seminar taught by Professor Stephen E. Silliman, a hydrologist and associate dean of Notre Dame’s College of Engineering. The seminar included a one-week trip to Haiti to repair wells and teach Haitians how to maintain water pumps. As a senior, Yoches heard about Louverture Cleary at a Notre Dame Service Fair while he was mulling postgraduate options. “I was looking for programs where there was community,” he says. “I didn’t want to go somewhere by myself; I wanted to be living and working with other people.”

Although teaching was not something he’d ever done before, he slipped fairly comfortably into the role. “I wouldn’t say it’s easy, but after a while you kind of get used to it and know what you need to do. Sometimes there’s some language barrier, but the children are just amazing in how much they learn.”

Steve Keppel was a marketing and psychology major who held a summer internship with an advertising firm. The experience convinced him to try something other than “just finding a job” after graduation. Like Yoches, he was attracted to Louverture Cleary’s community life, and he believed volunteering “would help my Catholic identity as well. But I didn’t know anything really about Haiti, so in some ways I took a leap of faith.” He signed up to teach English, but his role turned into “much more.” In his first year at the school he was involved in an environmental project out in the neighborhood, organizing a trash-collection system and leading community meetings. In his second year he was appointed the school’s projects director with duties that included creating an alumni organization and helping graduates to develop business plans.

He also took on the directorship of an Economic Growth Initiative project aimed at helping Haitians secure venture capital to start up new businesses. “Opportunities were available here, especially for someone with a business background, that I never expected when I came down,” he says. "Who knows what I’ll do in the future, but I know that I’m not interested in sitting in an office all day

.***

For Yoches, Keppel and other volunteers and staffers, the day begins at 7 with a prayer meeting in the school’s chapel. This morning the group’s prayers are for the family of the slain student. There are also some multilingual prayers for peace, led by one of the school’s security and maintenance workers who was recently part of a confirmation class at the school and is considering entering the seminary. As the volunteers pray, two dogs in the middle of their circle of chairs interrupt naps to scratch and snap at fleas.

At 7:45, volunteers, staff and students gather on the basketball court for the flag raising. The students line up in neat rows, the girls in plaid skirts and beige blouses, the boys in well-pressed khaki slacks and beige shirts. First there’s a Scripture reading and the national anthem. Today’s reading is conducted in English; yesterday it was in French—the two languages are employed on alternate days. Then the Haitian flag, the school flag and the United States flag are hoisted. The appearance of the U.S. flag is a mild surprise to some fresh Stateside visitors, but it doesn’t compare with a doubletake moment yesterday as the newcomers traveled from the airport to the school: On a street not far from Louverture Cleary they were delayed by a Flag Day parade, complete with a band merrily blaring the U.S. “Marines’ Hymn.”

The other end of most school days is work time for students, staff and volunteers, though not today because of the early dismissal. Physical labor is part of the school routine for everyone. Students perform such chores as tending the compost pit, clearing stones from the soccer field, cleaning buildings, washing sidewalks and removing debris from the construction projects that never seem to end at Louverture Cleary.

Most of the construction and rehabilitation work done at the school is performed by in-house labor. When special skills are needed, the Haitian Project’s president, Moynihan, imports volunteer experts from the States. The venture starting today at Louverture Cleary is to install solar power collectors to supplement a diesel generator and help reduce electricity bills. An architect and a solar-power specialist from the States are visiting for a few days to design and plan the project. When they leave they’ll turn its execution over to volunteers like Peter Yoches.

Neighbors of Louverture Cleary School consider themselves lucky to live near an institution where service and work are a way of life. The school shares water from one of its two wells with the local community, and volunteers can often be found outside the compound where they have set up a trash separation-and-disposal system and added a few trash cans along the street. Inside the campus, all trash is either recycled or burned.

Students, in consideration of their free tuition, are expected to serve the neighborhood by keeping it clean, caring for sick and orphaned children, and doing chores for disabled adults. The older students hold classes for illiterate residents of the neighborhood. All of this is in keeping with the school’s motto: “What you receive as gift, you must give as gift” (Matthew 10:8).

***

During Carnival week in February 2004, Haiti’s simmering political pot boiled over. President Aristide abandoned his office and his country after rebels took control of Haiti’s second-largest city, Cap-Haitien, and were rumored to be marching on Port au Prince. Carnival time happens to be a break week for the school, and the volunteers were scheduled to spend the week in the Dominican Republic, the more peaceful, tourist-oriented country that shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti. As heavily armed pro-Aristide gangs called chimeres ranged closer to Louverture Cleary’s campus, Patrick Moynihan took his family back to Illinois and sent the volunteers to Santo Domingo. He gave them the choice of returning to the States or remaining in the Dominican Republic until the crisis passed.

Keppel and another ND grad, Adam Osielski ‘02, remained. “We really wanted to come back to the school,” Keppel recalls. "We realized that without the volunteers the school wouldn’t re-open, and we knew we could wait it out. But after a week and a half things were getting worse, and we were saying to each other, ’We’re not going to be able to make it back.’ And then one day we woke up and saw in the newspaper that Aristide had left, and Haitians who were living in the Dominican Republic were celebrating. So after about 17 days we were able to go back."

Osielski, who majored in French and theology and was a volunteer at Louverture Cleary for two years, says the return to Port au Prince was “a little eerie. There was still unrest, and we didn’t know how secure the city was. But the Marines were there and the U.N. force came soon after.” Moynihan and his family also returned, and, slowly, the other volunteers did too. “School was back to normal in a few days,” says Osielski. And that, Keppel adds, "was a defining moment

***

Patrick Moynihan’s own defining moment occurred some years earlier. “I had a very standard Pauline conversion,” he says, one that grew out of some serious introspection about his job as a futures and options trader with the commodity trading firm of Louis Dreyfus, Inc. He was good at it, and it paid well enough to give him a comfortable house in the suburbs and two cars. But he felt uneasy when he thought about the kind of work one of his brothers, a plant biologist, was doing.

“As a trader I earned far more than my brother, who was helping to create plants to produce more food for the world—the same products I was trading. At the same time, my sister, whom I always regarded as a harder worker than me, lost her job due to a poor management decision in her company, and her pain over this had a big impact on me.” A question began nagging at him: “Why did God create a world where people, even from the same family and regardless of the purpose of their work, are rewarded so differently?”

The question would not go away.

The answer was an epiphany: “I came to understand that our talents do not belong to us but to the common good.” Convinced that he had to redirect his talents, and with the consent and support of his wife, Christina, the Moynihans sold most of their possessions and moved to Haiti in 1996 with their children, Robbie, then 2, and Mikhaila, 1. (They have since added Timmy and Marianna to the brood.) Having taught high school briefly after college, Moynihan’s quest led him to Louverture Cleary, a small, rundown boarding school and orphanage, adrift and heavily in debt. Within four years, almost by force of personality, he paid off the debt, established an endowment fund and was well on the way to transforming it into today’s thriving educational campus. These days the family divides living time between Haiti and Illinois; they estimate they’ve now spent a cumulative total of three and a half years residing in Haiti.

Moynihan is an energetic and highly effective political operator, although he’d object to that phrase. His thoughts tend to outrace his speech, and listeners find themselves coping with unfinished sentences as he plunges on to new topics. In the Miami airport terminal one day last spring, he was at the center of a small crowd of people whose nucleus included the Haitian Project’s second-in-command, Reese Jarret, and a handful of volunteers from the States heading for Louverture Cleary to lend their professional skills to school projects. Some others who gravitated to the group as it waited for the boarding announcement for American Airlines flight 803 to Port au Prince included James B. Foley, the U.S. ambassador to Haiti, and Bobby Duval, a middle-aged Haitian with a sunny disposition who runs a sports program for children in Port au Prince’s worst slum district, Cité Soleil, because he believes soccer and basketball teamwork can help overcome the animosities that plague his country.

A few days later on a return flight, Moynihan found himself sitting next to Andrew Young, the former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, who was going home from a visit in Haiti where he exhorted the country to do a better job of distributing its wealth. Some would call these encounters luck; Moynihan prefers to think of them as opportunities provided by the Holy Spirit to spread his message of hope for Haiti’s future.

Whenever he’s in Haiti, everyone at Louverture Cleary is acutely aware that the boss is around. He meets with staff members, volunteers, students, teachers, cooks and groundskeepers, prodding for information, poking for problems he can help solve. He happens to be away from the school grounds on an afternoon when the auxiliary bishop of Port au Prince, 44-year-old Pierre-Andre Dumas, drops by. Alerted by cell phone, Moynihan hustles back to the school to huddle with the prelate for a report on his visit to the school a few days earlier when he administered the sacrament of confirmation to some students and staff members. The shortage of Catholic parish priests in Haiti is so severe, Bishop Dumas says with sadness, that many children go unbaptized and never receive other sacraments.

During a discussion of conditions in the country, Dumas tells of a university student who was kidnapped recently and held for an outrageous ransom. When she said she couldn’t pay, her captors gave her a choice: call someone who can, or be killed. Kidnappings are so common in Haiti that such stories come unbidden from almost everyone. Although the student was released unharmed, not every victim survives. Moynihan and Dumas agree that this danger must be stared down, and Moynihan says he’s instructed everyone not to pay a ransom if he should be kidnapped.

***

On a late-spring morning when the oppressive heat and humidity build toward an evening storm, a van carrying Moynihan and two volunteers—ND’s Steve Keppel and a Saint Louis University alumna, Gwen Altenhoff—is driving into Port au Prince. The main roads in the city are paved, but on most side streets whatever ancient paving may once have existed has crumbled into rubble, and to drive on these streets is a tooth-jarring experience. Open sewers run along the sides of many streets, and at major intersections local women congregate to hawk food and household items to passersby —Haiti’s version of open-air 7-Elevens. Some Haitians sell their wares from makeshift lean-to’s along the side of the highway. Some of these huts, fashioned of scrounged scraps of wood, metal and tarpaper, double as residences.

The school van pulls into a parking place at an upscale building that houses Sofihdes, a development finance bank that supplies credit with extended repayment schedules to Haitian manufacturing firms and agribusinesses that can’t qualify for commercial bank loans. The group enters one of Port au Prince’s rare air-conditioned buildings and is passed by a security guard up to the second floor, where bank officials greet them in a conference room that would look completely at home in New York or Chicago. The contrasts —tasteful décor, relief from the enervating heat and humidity, coffee served in china cups around a polished wooden conference table—are a bit disorienting. Today’s meeting has been arranged to continue earlier discussions of a plan that’s dear to Moynihan’s heart—establishing a one-year course in entrepreneurship that will be available to university graduates with work experience who have ideas for starting a small business. There is enthusiasm on all sides of the table for this project, but the stumbling block is finding underwriting.

Moynihan, with an optimism stemming from confidence in his skills at raising money, thinks that may be a minor bump, and Michèle César Jumelle, one of the three Sofihdes officers at the table, agrees with him. Moynihan offers to explore funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development and some of the multinational businesses that have a stake in Haiti, and he deputizes Keppel and Altenhoff to work with the bankers to put a detailed proposal on paper. As he prepares to leave, Moynihan tells Jumelle that she is a role model for the female students at Louverture Cleary, where young women now make up slightly more than half of the student body, a rarity in a society where “educated woman” is almost an oxymoron.

Given Haiti’s tortured history, intractable poverty and ongoing violence, many people have given up hope for its future. You won’t hear that from Patrick Moynihan, although he admits it’ll take a lot of hard work by a lot of people, inside the country and out, to bring much hope into the picture. Creating an educated middle class of Haitians and seeding a network of small, job-creating businesses is a critical part of the solution, and he’s proud that Louverture Cleary School and institutions like it are making progress toward that goal. He takes satisfaction that in most years 100 percent of the graduates of his school pass the state-administered baccalaureate exam. And though the school is young, it already boasts a cadre of alumni with university educations and jobs in Haiti’s work force.

Although Moynihan operates comfortably and effectively in the secular world, he is also an ordained deacon in the Catholic Church and a missionary. That gives him a prophetic outlook on life that’s anchored solidly, even radically, in his faith. His core mission, as he articulates it, is simple. He proposes to obliterate poverty —in Haiti, for starters—by converting the people and institutions that produce it. “Poverty is not simply the result of a certain sector of society making poor choices,” he says. “God does not create poverty; all of us do that. Poverty is a combination of all sectors making poor choices, and it is unique to Catholic theology and social teaching that those of us who are not poor must seek participation in poverty, just as it is obligatory to help those who are poor out of their material poverty.”

To end the kind of poverty that grips Haiti, he says, will require nothing less than “the conversion of all people—our students at Louverture Cleary, the commercial sector of Haiti, government officials throughout the world, the rich and the poor, the workers and the managers, the laborers and owners. We must all seek to understand how our choices impact others, and to know what good choices need to be made. What it has taken all of us to make, it will take all of us to unmake.”

With help from volunteers like Peter Yoches, Steve Keppel, Adam Osielski, Reese Jarret and a lot of Stateside support, he’s working on that.

Walt Collins, the former editor of this magazine, teaches in the American studies department at Notre Dame.