When I was growing up in Maryland, Saint Patrick’s Day always meant the Wolfe Tones. Along with the smells of soda bread and corned beef and cabbage, the Irish folk music would waft throughout the house every March.

The most frequent musical choice was one of their live albums, Live Alive Oh, released in 1980. As the record spun and needle scratched, small speakers pumped out songs about James Connolly and a wide-brimmed hat, a heaven for sailors and a united Ireland. Those songs were the foundation of my Irish heritage.

But what I really remember is the sounds of the crowd on the album. The Wolfe Tones weren’t playing in a studio, with a thousand chances to get it right — they were doing it with no safety net, and inspiring an audience of hundreds, thousands, maybe a million in my child’s mind, to clap and sing and beg for one more song, just one more.

Music has always been one of the best parts of my life: I love listening to it; I love playing it. But nothing compares to seeing it performed live, witnessing the voice and persona of an artist spring to life beyond the stereo and stand in front of you and countless others, willing to give creating art on the fly a try.

I remember, in the years when album sales were still a viable business, how valued live records were. My siblings and I would keep an eye out for independent music stores on family vacations, and we would marvel at the ones that carried bootlegs, exorbitantly priced beyond our reach in strange discolored packaging with handwritten track lists. We taped an R.E.M. concert off a local radio station and rented videos of Woodstock and Monterey Pop, trying to sneak though the boundaries of geography, time and technology to a place in the awed crowds.

My first real concert experience was a double bill of Bob Dylan and Phil Lesh in the summer of 2000 at Merriweather Post Pavilion, a thickly wooded outdoor venue only a few miles from where I live now. It was a surreal wonder to be so close to a legend, no matter how aged and decrepit his voice had become; to figure out each song as Dylan tinkered with arrangements and lyric delivery; and to hear him sing “Blowin’ in the Wind” as an entire pavilion transcended everyday cares and worries to just sing along and float away on guitars.

I’ve been lucky enough to witness a lot of moments like that: U2 singing “Walk On” with a gaggle of New York City firefighters at Notre Dame’s Joyce Center in their first performance after 9/11; Van Morrison crooning “Raglan Road” at a Dublin theater; Kings of Leon blowing the doors off a dank Baltimore club long before they were curdled by fame; Neko Case’s voice ringing in D.C.’s 9:30 Club like a church handbell choir; and so many more, from Leonard Cohen shedding decades at Merriweather with a chorus of “Hallelujah” to the Pogues vamping endlessly on the refrain to “Fairytale of New York,” as fake Christmas snow fell softly from the 9:30 Club’s ceiling onto the shoulders of a waltzing couple.

For me, going to concerts is like Catholic communion in the “small c” sense. There are only so many times in day-to-day life that you can come so close to something as transcendent as the spontaneous creation and appreciation of art, with a crowd around you hearing, clapping and singing to your equal measure.

Even when it’s bad, it’s good. You get the funny memories of the incomprehensible punk or glam band opening for a headliner, or suffer through the millionth rendition of “Margaritaville” in a local bar, but you do it with everyone else within earshot.

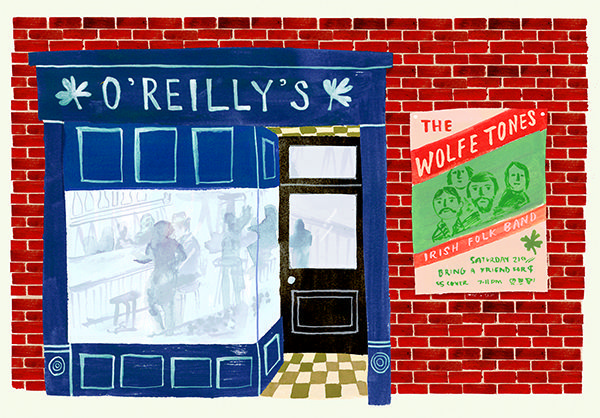

I’ve seen the Wolfe Tones in concert on two separate occasions. They are obviously out of their prime, and the original band isn’t together, and the notes don’t ring quite as true as before. But that doesn’t matter. When they pick up their instruments and start singing their rebel songs, I’m lifted from a New York or New Jersey bar back to my childhood home, with a stomach full of soda bread and the smell of corned beef and cabbage sifting through the early spring sunlight.

And everyone else in the room comes along with me.

Liam Farrell is a writer who lives in Maryland. If time and geography were no obstacles, he would go see R.E.M. in 1985, The Clash in 1980, Gram Parsons in 1973 and Otis Redding in 1966.