“The first thing you should know is that America still does make steel. Three-quarters of the steel that America uses — almost all of it — is produced domestically.”

This was probably news to the Notre Dame students who had gathered in a DeBartolo Hall auditorium last week to hear The New York Times’ Washington correspondent Binyamin Appelbaum speak about the economic consequences of the 2016 presidential election — and whether Americans in low paying jobs might expect their employment outlook to change for the better.

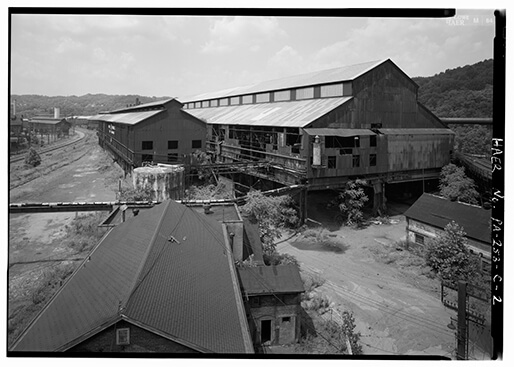

Steel “is not, however, produced in Monessen, Pennsylvania,” Appelbaum continued, using the town near Pittsburgh as a representation of the United States’ lost status as the world’s leading steel producer. “And the reason has nothing to do with the Chinese. The reason has to do with changes in technology.”

Steel manufacturing today, he explained, mostly uses scrap metal and employs fewer laborers who work in smaller factories that are typically located close to some of their primary customers: the car factories of the South.

“And people in Monessen are actually surprisingly aware of this, because they know something about steel. They don’t think the Chinese took their jobs. They know their jobs, to the extent that they still exist, are now in North Carolina,” the reporter said. “The people of Monessen, for the most part, do not dream about steel-making anymore. They do not expect that there will ever be a steel factory on that site again.”

Yet a rhetoric of restoring lost steel and coal jobs runs through the current presidential campaign.

“It’s really easy to tell voters that our problem is that someone else is screwing us. That if we could just get one over on them, they would feel the pain that we are feeling, and we would feel the prosperity that they have supposedly taken from us.”

But the globalization that so often has taken the blame for the downfall of the American working class isn’t all bad, Appelbaum argued, showing the audience pictures of Galesburg, Illinois, the former home of a massive Maytag appliance factory that has moved to Mexico.

“This is a giant rail yard on the outskirts of town, it’s operated by BNSF,” Appelbaum said. “Essentially the sole purpose of that rail yard is to transport goods from China to American consumers. That is why it exists. And these are now the highest paying blue-collar jobs in Galesburg. And they’re good jobs. They’re every bit as good as the jobs that used to be at the Maytag factory, in terms of pay, benefits, pretty much any other measure you’d like. Many of them are better jobs. I met a guy who’s making three times as much as he ever made at the Maytag factory,” Appelbaum said.

“On the outskirts of Galesburg there’s a pork plant owned by a Chinese company,” he went on to say. “And it packages American pigs and ships them on BNSF railcars to the west coast and over the sea to China.”

Local adaptations to global economic transformation like these mean that American consumers can buy cheap products from abroad while made-in-the-USA products may compete in markets that were not always available to American companies. And that, proponents of globalization say, is a good development for the country’s economy.

“American manufacturing output is in the highest level in history. We make more stuff today in the United States of America than we have ever made before. It’s a remarkable statistic. Employment has plunged. Productivity has spiked, and the net effect is that our manufacturing sector is, by that measure, healthier than it’s ever been before,” he told the audience.

But some are left behind, he noted. As manufacturing jobs move overseas or become redundant due to technological improvements, those who aren’t trained to enter today’s service workforce fall behind.

As Appelbaum has written in the Times, we will soon be living in the United States of Home Health Aides, as the nation’s population of senior citizens increases and more people are needed to take care of them. But politicians talk about getting manufacturing jobs back rather than creating better opportunities for those entering the service sector.

“We have a population of 850,000 workers in the home health care industry making an average wage that is not enough to get above the poverty line if you happen to be supporting a husband and two children. Average! That’s not a good situation, and it would be nice to hear our politicians talking a little bit less about how to create more steel working jobs and a little bit more about what could be done for those home health care workers,” Appelbaum said.

Chances are that very few of the Notre Dame students in the audience will ever work as home health aides. Their prospects are good, and yet students wonder what awaits them in the job market. I will put my head on the block and say that the forces of globalization and technological advances aren’t going to slow down much, and though most Americans do benefit, those without a college education or access to it will likely suffer.

In that light Appelbaum’s prediction that little will change no matter who wins in November is rather dim.

“There ought to be consequences. What this election is telling us is that there are things that are broken and things that need to be fixed. So, I wish there were more likely to be consequences from the 2016 election,” he said.

Rasmus Schmidt Jorgensen is a student at the Danish School of Media and Journalism and an intern at this magazine.