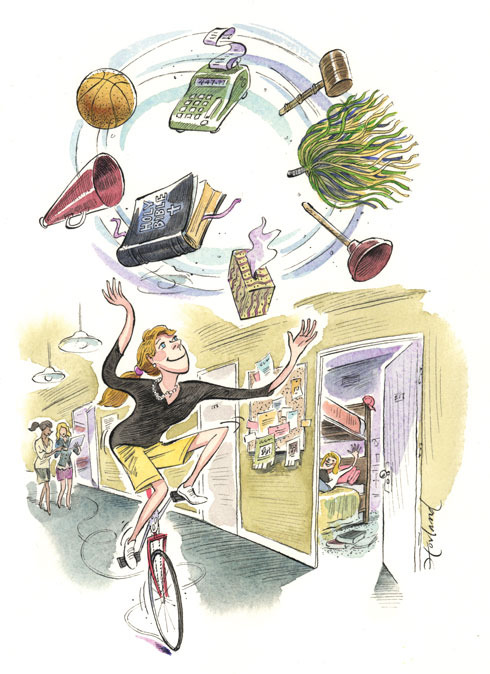

Should the clerical gig ever fall through, Father Pete McCormick, CSC, has the makings of a master juggler.

Stanford Hall’s priest-in-residence, the wiry, upbeat McCormick ’06M.Div. is also a student in Notre Dame’s executive MBA program and the chaplain of both the Notre Dame Vision summer retreats program and the men’s basketball team. Within the next three hours, he must pack a bag and catch the flight to a road game against Florida State, but he’ll spend half that time in a quiet parlor in Corby Hall, a silvery MacBook Pro on his lap, talking about his part-time job as the director of rector recruitment in ND’s Office of Student Affairs. If he’s uncomfortable with the timing, it never shows on his expressive, bespectacled face. He doesn’t even glance at his watch.

In fact, McCormick does juggle, a little. “But not well,” he says.

He may be selling himself short. The 36-year-old priest’s main claim to campus fame is the six years he spent in Keough Hall, where his good nature, lack of pretension, clear sense of purpose and — above all — his ability to do many things well at once made him an excellent rector. Today he’s using those gifts to help shape the future of that job — one that’s unique to Notre Dame and essential to the kind of education as formation of the whole person that the University seeks to provide.

Last year, Notre Dame hired seven new rectors to restock vacancies in its 29 undergraduate halls and two graduate residences. Six of those hires are lay people. That rate of turnover and the proportion of lay to professed religious who apply are becoming the norm — a long leap from the days before coeducation when hall leadership was the exclusive province of Holy Cross priests and brothers who often stayed a decade or more and made the dorms extensions of their personalities.

Driving these changes is the decades-long decline in religious vocations in the U.S. Catholic Church, a steady evaporation of the traditional talent pool that has made religious orders more reluctant to release their members from community life and core ministries into isolated assignments. Today, Holy Cross itself sends fewer men into the dorms. The resultant gap has Student Affairs turning increasingly to the laity to maintain a residence hall system that the alumni consider the heart of their Notre Dame experience.

“We did not do a good job of anticipating the bubble bursting,” McCormick says. The problem hasn’t been finding successful rectors but the amount of time and effort required to find them. What once took little more than advertisements placed in a few carefully selected magazines is now a matter of building fertile relationships.

McCormick’s 20-hour-a-week job is new, a set of duties that once fell under the broad job descriptions of such senior Student Affairs staff as Sister Jean Lenz, the late and much-loved former rector of Farley Hall. Unlike his counterparts at most U.S. universities, McCormick is not just looking for freshly minted professionals with master’s degrees in higher education administration. Identifying the right person means locating candidates who can positively influence students’ spiritual, academic, social, moral and emotional lives.

“I believe in all honesty that our alums get it the best,” says the graduate of Michigan’s Grand Valley State University who, like many current rectors, managed to learn ND on the job. “They understand implicitly what we’re trying to do because they’ve experienced it themselves. And even if they aren’t interested, they know people who would be good fits.”

So after working with Holy Cross and current rectors to fill new vacancies, McCormick tries such campus partners as the Alliance for Catholic Education, the Alumni Association and the Master of Divinity program, and external sources, mostly in Catholic higher education. What he really wants is to get people actively thinking and praying about the job as a possible career path — if not now, then maybe in a year or two.

You may not know it yet, but the future rector he’s looking for could be you.

A ministry of presence

At 11 o’clock on a Wednesday morning, Noel Terranova’s eyes belie his crisp version of Notre Dame business casual — a blazer, blue Oxford shirt and khaki pants. The Keenan Hall rector was up until 3 a.m. again. It wasn’t the controlled, all-hours partying that welled up the instant the University closed for two days under a rare, countywide snow emergency. It was a student who had come to his apartment, struggling to cope with a tragedy back home.

Morning came anyway, with its insistent flow of maintenance requests, “urgent” emails and all the expectations of the University’s 9-to-5 staff.

There is no quintessential rector anymore, if there ever was. But halfway through his second year, it is evident Keenan Hall’s rector brings a lot to his job, especially to moments like that late-night knock on his door. On hiatus from his doctoral studies, Terranova ’05MTS, began his professional life as a campus minister at his undergraduate alma mater, Villanova. He owns a house in South Bend, where he sometimes takes his two dogs on his day off.

Recently, while discussing plans for the Keenan Revue with residents over lunch at North Dining Hall, Terranova. 32, introduced his long-distance girlfriend via the FaceTime app on his smart phone. He kept the call brief, just one illustration of the challenge of maintaining balance and boundaries in a life that affords little privacy.

- Related articles

- But we already have a Jumbotron . . .

Every school with residence halls employs people to meet the comprehensive needs of live-in students. Leadership models vary, says ND vice president for student affairs Erin Hoffmann Harding ’97, but most U.S. universities follow one of three broad paths. Many employ a hall director, often a student-affairs professional, who may manage more than one dorm. Some elite institutions appoint faculty masters who lead the dorms with staff support and may actually live there with family. Catholic colleges typically follow a third way, supplementing the hall-director model with a chaplain-in-residence who provides spiritual counsel.

Notre Dame’s approach is unique. It’s not just the stay-hall system, the undergraduate resident assistants, the relatively modest size of ND’s dorms or the fact that each one has its own chapel and Masses — all of which reinforce the community feel and make the “What dorm did you live in?” question so important to alumni. It’s the rectors themselves.

“We ask our rectors first and foremost to think of themselves as pastors of this community,” Hoffmann Harding says. The tasks of forging bonds, fostering faith and calling the plumber, or of knowing what to do when a student opens up about divorce or violates the alcohol policy or needs to choose a major, fall primarily to the one person responsible for each dorm.

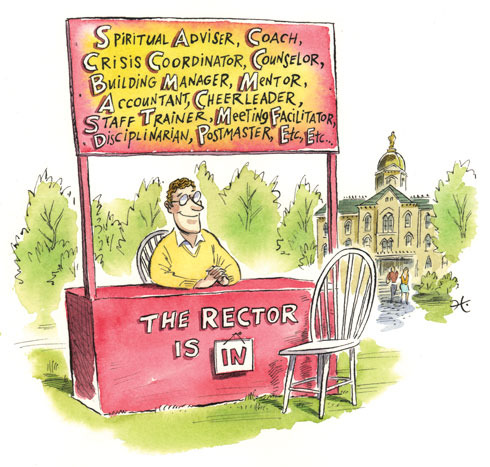

Capturing this breadth, the rectors’ job description runs about a page and a half of tiny type, 44 line items under the four broad categories of “pastoral leader,” “chief administrator,” “community builder” and “university resource.” In everyday terms, the role comprises some combination of crisis coordinator, liturgist, counselor, disciplinarian, staff trainer, building manager, meeting facilitator, mentor, cheerleader, accountant, postmaster and even data-entry specialist.

At its heart, though, it’s a ministry. Job number one when you read the position description from top to bottom is “active and visible” Christian witness. Not far down the task list is “establish a ministry of presence.” In other words, it’s about being there, or as Sister Lenz once put it, “sharing life with our students.”

Key to the rectors’ success is their selection of their staff — two graduate assistant rectors who can help with anything from prayer life to signature events, and one undergraduate resident assistant for each of the dorm’s sections. Done well, says Heather Rakoczy Russell ’93, associate vice president for residential life, the staff models the faith and love of Christian community, which ripples outward through the sections to the whole dorm and across campus.

That’s only the beginning. “When we let the students loose on the world, they’re called to be the best version of themselves and to transform the world,” Russell says. “I know that sounds lofty, but if they truly have a sense of Christian community, then that’s the potential impact.”

That’s why rectors matter.

“What other university has someone they call a rector? It sounds like an arcane, ecclesial type of term,” Terranova muses. “It means to make straight. If you were to rectify something, you would correct it, put it on a straight path.”

Life gets messy, he says. “And to have someone, a leader within your community, who can help you make sense of all that — that’s what I see a rector as.”

The best part of his work at Keenan, he says, is standing up with a student after hearing what he’s going through, giving him a hug and reassuring him that he’s loved and supported — whether that means checking in from time to time, rallying his friends, or placing a call to an academic adviser or the on-call psychologist at the University Counseling Center.

Receiving that kind of trust from a young person is rare, even in campus ministry, Terranova explains, but at Notre Dame it comes with the job. “Because I’m a rector,” he says, “this student came to me.”

Taking the reins

There’s nothing new about young lay rectors like Terranova. Kathleen Cekanski-Farrand ’73J.D. and Joanne Szafran ’73M.A. were the first female rectors tapped to lead women’s dorms — Badin and Walsh halls, respectively — although in 1972 their vocational status attracted somewhat less notice than the gender of the newcomers under their care. The best institutional memory says 15 years passed before a graduate student from Ireland, Joseph McKenna ’88MCA, became the first lay male to try his hand as rector, in Sorin College.

Today, lay men and women outnumber Holy Cross rectors 12 to 10. Experience has taught Notre Dame students that a rector’s age and state in life only change what they bring to the job, which is even open to the right married candidate. Above all else, Father McCormick says, students want a rector who understands them.

Nearing the end of her ninth year in McGlinn Hall, Sister Mary Lynch, SSJ, is the most tenured woman on the roster. A Josephite from Philadelphia, Lynch says her sisters — most of whom are active or retired teachers — can’t see what she likes about college life.

For her, the career choice made perfect sense. Shortly after completing her theology degree at Notre Dame in 1981, Lynch began a 10-year career in college campus ministry out east, then returned to Philadelphia to fill various posts and be close to her aging parents. In 2005, serving as the order’s formation director, she decided she no longer wanted to sit in an office “churning out prayer services.”

“I missed being around people and students,” she recalls. “And I love this age group.” The transition was hard at first, the sense of isolation acute. Her first group of seniors had endured some turbulence. Lynch was the third rector they’d seen in their four years and, though they welcomed her, she felt the tensions that accompany any change in regime.

Naturally Lynch is now the one helping freshmen adjust to Notre Dame. Like all rectors, she meets with students one-on-one in their first semester as the novelty of being away from home wears off. They cover everything: course demands, the pressure they put on themselves, when to do laundry, how to do laundry, what to eat. “The dining hall can be overwhelming,” she says.

The ice broken, Lynch asks the students about their weekend nights, not to get them in trouble, but to fortify them. Blackouts are her greatest fear for them. “They don’t expect that to happen with the way they drink,” she says. “They think that’s for hard-core alcoholics.”

The most vital message Lynch sends during that first meeting in her cozy, immaculate apartment may be nonverbal: that her door is open, at least after 11 a.m. Mornings are for her and for prayer. After that, the bowl of Snickers and KitKats she keeps is a draw, especially in the evenings when most students are around. Hospitality is part of her Josephite charism; fairness and consistency are important to her personally. She believes those qualities are characteristic of McGlinn as a whole and help to form the women who live there.

When they move out, she hopes to see in them “a maturity and a confidence that they are capable of doing just about anything they put their mind to; that they are making wise, healthy choices for themselves.” They’re good young women, she says, and they don’t always know it.

Setting an example

Annie Selak was 27 when she moved in to Walsh Hall with a graduate theology degree and residence hall experience at the University of San Francisco on her resume. Selak is outgoing and youthful and was mistaken for a student several times during her first dorm move-in day. She says entering in 2010 with a group of five mostly young, lay rectors was like diving into a fishbowl, with students’ eyes tracking everything they did, from the amount of time they exercised to how they approached friendships and dating. They felt acutely the challenge to model a balanced, Christian life for their residents.

Her age is both an asset and a hindrance, she says. On the one hand she can readily recollect the intensity of roommate conflicts and other student troubles — stress, depression, how to reach out to a friend whose parent has died.

On the other: “I think the assumption was that we were going to be much more lax. And I think as it turned out that wasn’t the case.”

Students need to know the difference between a rector and a friend, she says. Rectors have professional responsibilities. Mutuality doesn’t come with the role.

She’s still mistaken for a student, even by students. Recently, while standing in line at The Huddle, Selak and another rector were invited to a party by young men who’d been talking about the five handles of vodka they had. “We just called [their rector] and said, ‘Hey, you might want to greet these guys at the door and tell them not to invite rectors to their party.’”

Being a rector gave Selak a welcome opportunity to use her gifts and be her full self. “I don’t think a day has gone by when I felt like this job wasn’t tapping into everything that I am and everything that I have,” she says.

Selak’s boss, Heather Rakoczy Russell, who started her student affairs career as the rector of Pangborn Hall, says the all-encompassing nature of the role isn’t for everyone. The challenges tend to fall into three categories regardless of age, gender and vocational status.

One is the rectors’ need for a community of their own, a challenge spared Holy Cross priests because of the anchorage they have in Corby Hall. Another is that the job tends to attract “helper” types who won’t take time off no matter how capable their hall staff is or how many times Russell encourages them. Sister Lynch admits she didn’t take a single day off in her first seven years. Now, her Mondays are sacrosanct. “I’m a much nicer person,” she says with a chuckle.

Career path is a third concern, so Russell and her colleagues are working to build professional awareness of what rectors do, both around the University and among other schools. Rectors are hired and renewed on one-year contracts. But the ideal is that they’ll stay four and see at least one class all the way through.

While rector tenure has fluctuated considerably for decades, the share of those with four or more years of experience has dropped from 69 percent to 52 percent since 2009.

Now approaching the end of her fourth year, Selak has applied to doctoral programs and has shared that news with her residents. “I think it’s healthy to have them know that this community doesn’t revolve around me.” Walsh women have to take ownership of their dorm, she says, whoever their rector may be.

On that front she’s especially optimistic. The hall calls its approach to common life “Walsh Love.” It takes hundreds of small and spontaneous forms, like baking cupcakes for a senior the night before the GRE or sharing a cry with a stressed-out friend. Each week, though, the women issue themselves a formal Walsh Love Challenge via the Stall Street Journal posted in their bathrooms. As classes resumed last fall, the call for every resident was to introduce herself to a newcomer and invite her to lunch.

That unique interpretation of the vision to build community out of a four-year collection of random room assignments is the “unified diversity” of Notre Dame’s residence halls, what Erin Hoffmann Harding calls the University’s “secret sauce.” The dorms don’t have to be carbon copies so long as they are havens of Christian community that maintain the same standards of conduct, nurture moral and spiritual growth, reach out to all students — especially those on the margins — and help them find their campus home, whether in their studies, an activity or the residence hall itself.

“We really think of that as a huge part of their experience. We want them to be known individually,” Hoffmann Harding says. It’s what makes Notre Dame different, she adds. “And I think we can prove the results.”

The Spring 2012 senior survey found 93 percent of Notre Dame seniors reporting satisfaction with the sense of community on campus, compared to a median of 78 percent among a set of highly selective private colleges and universities. Community is also the best available explanation for the extraordinary bond the alumni feel to the place.

Not long ago, an old Keenanite grieving the death of his spouse wanted a Mass celebrated in her memory in the hall chapel. He contacted the rector — a stranger more than 30 years his junior. Which suggests that, alongside beloved faculty, the quads, the lakes, the Grotto, the residence halls and the Lady on the Dome, rectors themselves stand among the most important links to a Domers’ core, the restorative symbols that shape who they are.

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine.