Editor’s Note: More than a decade ago, essayist Mark Phillips wrestled with how to remember loved ones and elders whose ethnic and racial bigotry he repudiated. That was the dawn of Barack Obama’s presidency, when many Americans believed such prejudices might be becoming a relic of the past. In 2020, Phillips’ reflections retain the urgency of now.

Promising that his all-white team alone was worthy of the scoreboard, his looming shrine, he thundered over the grunts and snarls of the boys scrimmaging on each end of the dry field. His players called him Boomer. The varsity was preparing to play a team with a black halfback, and I knew he had designated one of his runners to play the sacrificial role of the talented enemy halfback. From where I practiced with the junior varsity, I felt his booms: “Get the spook. Get that spook.”

None of us boys walked off the field in protest of the metaphorical lynching. I admit this with difficulty, but we loved the racist coach, who is now honored on the wall of fame in the football stadium at my old high school. He was the only one of my high school teachers to contact me after my father died during my freshman year of college. He drove to my home, sat with my family at the kitchen table and shared gently his sympathy.

Perhaps it’s insensitive of me to bring up my late coach in this way after so many years. When you’ve loved as many bigots as I have, knowing how to remember them can be as hard as that dusty, cracked ground upon which I felt the words “get that spook.” And perhaps Faulkner was mistaken and the past really is past — bigotry little more than a rusty whip handle unearthed at the site of a Mississippi plantation. I’ve heard that our current president is irrefutable evidence that bigotry in the United States is now a group of feeble old men peering watery-eyed through holes in tattered white sheets; that fear of racism is as irrational as fear of ghosts.

Perhaps I should let bygones be bygones.

A slur for a slur

On my way home from work on election day, I stopped for a beer. The Irish bartender glanced at my Obama shirt and told a joke to the guy on the stool next to me. “Did you hear that Obama is ahead?”

“No. Is he?”

“Yes — but that will change when the white people get off work and vote.”

I asked the same guy, “Do you know if they serve seven-course Irish dinners here?”

“Whaddya mean?”

“You know, a six-pack and a potato.”

My wife is mostly Irish and I’m partly, but my retort by slur was inexcusable, and, anyhow, you could say that my spirit of reconciliation was found wanting. I knew that stupid hate might sputter like old grease on the grill as soon as my plug for Obama was noticed in that establishment where a patron can scribble whatever he desires on a dollar bill before the bartender tacks it to the wall above the bottles of whiskey. Where the father of our nation gushes, “I like Boobies!”

Since election day, I’ve bought beer at the business where I heard the racist joke, and it wouldn’t be impolite of you to ask why. In my neck of the woods, that bar is one of the few with Guinness on tap, and I am a weak man, but the answer is also that some of my fellow Americans drink elbow to elbow there and — for me — climbing up on one of those stools can be like going home again.

The first bigoted joke I heard as a child was told by a friend who had heard it from his father. In my backyard, my innocent friend asked, “What did God say when he made the second n——-?” I still hear the birdy, quavering voice of my friend — who walked to church with me on Sunday mornings — as he finishes the joke by assuming the Word of God. In the punch line, God does not remind us that He created all people in His image or demand an end to lynching and holocausts and laughter at hatred. Instead — on the green grass of my childhood — He says, “Oops, burnt another one.”

Although I’ve made myself forget, surely I laughed. I was already fluent in the tongues of bigotry, though I never used the word dago in the presence of my best friend, who was Italian.

Fear and loathing

After he led us in prayer, thanking Our Father for supper, my own father made occasional ethnic slurs while telling us about his day at the power plant or commenting on some news he’d heard on the radio while driving home to our working-class New York town, where eventually Timothy McVeigh would grow up. Usually the slurs were spoken as if he were reporting the weather, but he was not so casual when race riots erupted in nearby Buffalo. He feared that the violence would spread to Pendleton, home to merely a few black families.

We once ventured into the inner city to cheer the Buffalo Bills, the blue-collar defending champs of the upstart American Football League. My father parked the car on the small, yellowed yard of a house on mostly boarded-up Jefferson Avenue, paid the owner a two-dollar fee, and marched us to the game among an influx watched — predatorily, I imagined — by blacks sitting on front steps and porches, whole families bemused at the sight of so many whites staring straight ahead with silly terror in their eyes as they hurried up the avenue of false promises.

Ticket scalpers and hot dog vendors hawked at busy intersections, and when we reached crumbling War Memorial Stadium — or the Old Rockpile, as it was called in western New York — my father said, for the second time that afternoon, “We’ll be lucky if our car isn’t stripped when we get back.”

Somehow my father and the rest of us whites worrying toward the stadium had come to the backward conclusion that blacks had a history of harming whites. Dad and I had given little thought to what it felt like for the two blacks who attended my school or the few who labored at the power plant, but now we feared being in the minority. Inside the decaying but thick walls of the stadium, things would be made right again: the coaches and quarterbacks and security guards would be white like most of the fans.

Even a boy could sense that football was the way America worked: a hierarchy of owner and directors and coaches and stars right on down to the wounded, grunting and anonymous offensive linemen on whose wide shoulder pads every touchdown rested. Yet our nation had two working-classes: one inside and one outside the walls.

Anti-Catholic

When he emigrated from the North of Ireland to the United States, my paternal great-grandfather carried the heirloom of anti-Catholic bigotry. Three generations of Phillipses lived in an Irish neighborhood of South Buffalo, and on their way home from public school my father and uncles and other Protestant boys often fought Catholic boys who were on their way home from parochial school.

My grandfather referred to Catholics as cat-lickers, though he married one who agreed to give up her faith. Before I met the woman I would marry, who has kept her faith, I suspected that Catholics had tails and horns — a fear she has mostly dispelled.

Until my grandfather took a new job in the power plant he had helped build, all of the Phillips men were disposable iron workers. In three separate accidents, my great-grandfather and two of his sons died on construction jobs. My grandfather broke two ribs and bruised a lung in another.

My father inhaled welding fumes all day in a plant so polluted with coal dust and fly ash that if he wore a white shirt, no matter how long he had scrubbed his skin after work, the cloth would gray as he perspired. My maternal grandfather broke a leg on a road construction job; two other kin survived crushing injuries on logging jobs; another lost several fingers in a machine shop. Nearly every iron worker in the family had a damaged back before he reached retirement age, and they were among the lucky ones. When their bodies were broken or lifeless, industry purchased new bodies. Helplessly, my father knew this. On a sidewalk in a nearby town we once passed a stranger in a grandiose suit, glittering watch, gleaming shoes; my father spit on the concrete and muttered, “You son of a bitch.”

My father, his killed grandfather and two killed uncles did put food on the table while they lived. They could have been limited to starvation wages or sent to the endless unemployment line; and weren’t they forever reminded? Aren’t we all? On some level they must have sensed that the privileged had twisted the word black into a definition for those who are perceived as lower class in America — and that their own skin pigment was no guarantee that they would be perceived as white.

In his book How the Irish Became White, historian Noel Ignatiev could be referring to my kin when he notes of his depiction of oppressed 18th and 19th century Irish-Americans, “I hope I have shown that they were as radical in spirit as anyone in their circumstances might be, but that their radical impulses were betrayed by their decision to sign aboard the hunt for the white whale,” which, he adds, “in the end did not fetch them much in our Nantucket market.”

During the hike to the Old Rockpile, Dad bought us lunch at a hamburger stand. On the sidewalk, he counted his change and realized that the black cashier had accidentally handed him a 20-dollar bill rather than a five; he got back in line, corrected the mistake, and explained to me, “They would have taken it out of her pay.” It was a warm autumn day, and as usual he was wearing a dark shirt that hid the coal dust, the blackness flushing from his pores as he perspired.

Still white

I never heard my mother use the racial epithets that were second nature to other adults in my family and neighborhood. I like to think she was too bright to be bigoted. She had graduated first in her high school class but didn’t attend college, as she explained it to me when I was a teenager, “because back then college was just for rich girls who wanted to find richer husbands.”

She grew up with American Indians. Her father’s small, swampy farm edged within a half mile of the Tonawanda Indian Reservation, where, until he died in his 80s, one of her uncles lived with an Indian woman in a cabin with no toilet. My mother’s younger sister married a man from the reservation, and although my grandparents loved their half-Indian grandchildren, their complaints about “lazy Indians” were sometimes slung at their gainfully employed son-in-law, and they were sure that “them Indians must have took it” whenever a possession disappeared from the farm. Until my grandfather landed a job on a state road crew when he was in his 40s, they were poor, but my grandparents could always visit the reservation to witness destitute poverty, to be assured that though they couldn’t afford to buy more than three pairs of underwear for each of their daughters, they were still white.

I was spending a weekend on the farm when the brother of my grandmother’s closest friend killed himself on the reservation. Charlie Moses lived with his sister, who telephoned my grandmother minutes after the rifle blast. Over the phone, my grandmother asked Arlene, “Was he drunk?” I begged them to take me along, but my grandparents ordered me to stay behind as they hurried out to their old American Motors sedan.

Early the next morning they returned to the reservation to clean Arlene’s parlor, and I went fishing in the muddy creek that shaped the sinuous east and north boundaries of the farm. I returned to the yard hours later dragging a stringer of gasping and flopping bullheads and rock bass, tormented by a cloud of mosquitoes, and encountered my grandmother kneeling on the grass with her hands plunged in a pail of soapy, pink water. I asked what she was doing, and she replied, “Trying to get brains off these curtains.” She held up a curtain and said, “Who ever would have thought Charlie Moses had so much brains?”

Civil rights

We danced to James Brown and Aretha Franklin, and perhaps the sensual celebration awakened us to the images and calls of truth arisen. By then it was 1970 and some of us paid attention when our American history teacher taught about slavery, the KKK and racial segregation, and he asked, “How come you don’t see anyone except whites in this class?”

Some of us were appalled by the old news footage of police assaulting peaceful civil-rights protesters with truncheons, torrents of water, snarling dogs and Southern law, and were stirred by the brave, truthful poetry of Reverend King, though by then he had been assassinated by a white supremacist.

When the school board banned Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice from the library, a small group of us protested, not because we admired the author’s murderous, misogynistic rage but because we possessed some vague understanding that his eloquence was an incantation of Emerson’s self-reliance come home to roost. We argued that the school was supposed to be educating us, and Cleaver was an American reality.

Of course, none of us walked off the football field: other players might have been granted our positions.

Family debates

Lincoln and Douglas we weren’t, but my father and I had a series of debates about racial issues. At first we disagreed about the banning of Soul on Ice, but as in all serious discussions involving race in America, we soon found it necessary to abolish boundaries and time — to visit George Wallace as well as Eldridge Cleaver, South Boston as well as Birmingham, and Africa as well as Harlem.

He never argued overtly that blacks were genetically inferior, but my father was opposed to court-ordered integration of schools and affirmative action and believed that blacks had accumulated more rights and opportunities than had whites. I was 17. My mother, who knew her socially defined and confined place, listened in silence to our debates, which began during supper and lasted for hours.

My father thought about our disagreements while at work and I at school, and each of us charged into the new evening armed with arguments we believed to be fresh and potent. My father actually asked a black worker at the power plant what he thought about the Black Panthers and reported triumphantly, “He told me they’re all crazy.”

We debated for three or four evenings in a row and then, weary from arguments that seemed to be going nowhere except into a recycling bin, gave it a rest. We mostly avoided each other until he came to me after two days of quiet and said, “You know, all that black and white stuff we talked about, some of it you were right. You still got a lot to learn in life, but some of it you were right.”

I nodded and looked away, embarrassed and proud like a son who has realized that for once his father has not let him win at basketball, that he has actually beaten his flawed hero. Which only goes to show that my father was right about one thing: even though I never again heard him utter a racial epithet, I still had a lot to learn about hate and love.

Hiding

He was slowly dying. Men seldom develop cancer of the prostate until at least age 50, but some studies have reported that welders have an earlier and higher incidence. He had been diagnosed with prostate cancer at age 40, and because it had already spread into his bones where it was inoperable, a surgeon had removed my father’s testicles to deprive the tumors of some of their hormonal fuel.

He continued to limp into the power plant to support his family. On the days when he was in too much pain to work despite the drugs, his fellow welders did his jobs and hid him in a storage room so the big bosses wouldn’t know to fire him. He eventually found it impossible to climb the stairs to the second-floor time clock and took an early retirement, which lasted several months.

He still was unable to wear a white shirt.

Mark Phillips lives near Cuba, New York. His memoir, My Father’s Cabin, was published by Lyons Press in 2001.

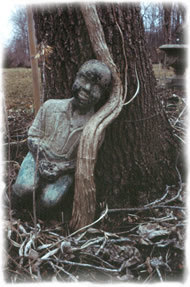

Photo copyright Don Nelson.