Anna M. Thompson decided to read one last email before calling it a day.

It was nearly 11 p.m. when the executive director of Notre Dame’s Marie P. DeBartolo Center for the Performing Arts (DPAC) clicked on the message from Greg Phillips ’66. Phillips had been in the Decio Mainstage Theatre audience a few hours earlier for the L.A. Theatre Works’ world premiere performance of RFK: The Journey to Justice.

“Keep up the good work of bringing all types of works here and continue to push the envelope of making us think instead of just sitting and being entertained.”

The line that ended that impromptu thank-you note has kept Thompson smiling for weeks. “That’s exactly what we’re trying to do,” she says. “Exactly.”

When Thompson arrived on campus in the summer of 2007, the University made a commitment not only to showcase some of the world’s top performing artists but also to help them cultivate new works to bring to the DPAC’s five stages.

“There’s a trust that we’re building not only with performing artists but with our own patrons,” Thompson says. “We know if they go home and talk about something for a week they’re not only going to come back they’re going to be more willing to try something else.”

Since the 2008-09 Visiting Artist Series, the University has showcased eight new commissioned works by such artists as the Kronos Quartet and Wu Man, the Richard Alston Dance Company and Tim Robbins’ The Actors’ Gang. The University has already commissioned at least six more works for the 2010-11 and 2011-12 seasons — most notably The Actors’ Gang’s anticipated stage adaptation of author Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States — in a growing effort to establish the University as a leader in the creation of new works in music, dance and theater.

“What if we had no more new music?” Thompson says. “What if we had stopped with Bach? What if we said, ‘Okay, nobody’s going to do better than that. Let’s stop now.’ If that happened the world wouldn’t have gotten to hear Mozart or Stravinsky. Can you image a world where nothing new was being created? I feel it’s our responsibility to make sure that doesn’t happen. I think it’s one of the most important things we’re doing right now. There’s a cultural legacy that we have to leave.”

Formerly the executive director of fine arts programming at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University in Minnesota, Thompson has long been an advocate for investing in the creation of new performance works, especially in the world of dance. She often likens such commitment to the arts as being as important to higher education as funding research in the sciences — both allow new discoveries and exploration of ideas.

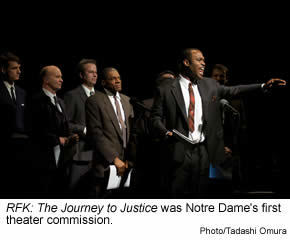

The response to January’s RFK: The Journey to Justice, the University’s first theater commission, seems to echo that sentiment.

The performances cross classic theater with old-time radio shows, featuring actors with scripts in hand delivering their lines into microphones placed around the stage. Written by playwrights Murray Horwitz and Jonathan Estrin, the production examines the Civil Rights movement through the lens of Robert F. Kennedy’s political life, showing his evolution from ambivalence to passionate race-relations crusader from 1960 to ’68.

Notre Dame served as lead commissioner on the project, with Stanford University, the University of Maryland and the University of Richmond also contributing.

“Notre Dame did what any good commissioner does,” says Susan Loewenberg, the founder and producing director for L.A. Theatre Works. “They gave us the money and left us alone. They trusted us to come up with something that was good. What they were able to do on their end was to put together discussions, a matinee performance just for students and professors; I even did a class about the politics of the play. It’s a wonderful way of exposing how you can use the arts in all kinds of ways.”

The addition of such educational opportunities across the University community, Thompson says, also can provide rare firsthand examinations into the creative process that can be applied in multiple disciplines.

“We can’t talk to Beethoven or Mozart,” Thompson says. “But to be able to sit down and have a conversation with [British choreographer] Richard Alston about a new dance piece is a very different experience, maybe a once-in-a-lifetime experience, for faculty members and students.”

Although the 2008-09 season was Thompson’s second as executive director, it introduced her first year of artistic programming. With the support of grants, donors and budget reallocations, Thompson was able to commission works by dance troupes Diavolo and Spectrum Dance Theater as well as the world premiere performance of a Terry Riley composition by the Kronos Quartet, a San Franscisco-based ensemble, with soloist and pipa player Wu Man. Since most of the money came out of a fund to pay visiting artists’ fees, Thompson says she had to be more selective in the performers she brought to the University’s stages.

“It may have shifted the way our season looked,” Thompson says “but it certainly didn’t affect the quality of artists we could bring to Notre Dame. The Kronos Quartet has now performed that work all over the country, and in every program it says ‘commissioned by the University of Notre Dame.’ That brings equity to the University, and it brings equity for a performing arts center that’s only six years old.”

Although Thompson doesn’t dictate the subject matter for commissions, she does seek out artists who will develop complex projects that fit the University’s mission. In addition to civil rights, a subject closely tied to the University through the work of former University president Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, Tim Robbins’ group presented The Trial of the Catonsville Nine. The play follows the trial of nine Catholic activists, most notably brothers and priests Philip and Daniel Berrigan, who entered the Selective Service offices in Catonsville, Maryland, on May 17, 1968, removed 378 draft records and burned them in the parking lot.

Loewenberg of L.A. Theatre Works says being commissioned by a university often provides a much greater chance for such works to be seen.

“It’s become very popular for foundations to commission playwrights, but 97 percent of them are never performed,” Loewenberg says. “They may do readings and workshops, and that’s that. If they aren’t sure they can make money off of it, especially in this environment, they won’t put it on.”

Thompson understands that.

“If I were a community theater looking right at the bottom line, I’m not going to be doing a play like RFK,” she says. “I’m going to do Bye Bye Birdie.”

Creating original works can take anywhere from 18 months to two-and-a-half years to produce, and can cost anywhere from $5,000 to $50,000. Thompson says her goal is to have between two to six commissions and at least one world premiere performance at the University per academic year. She also says that she hasn’t come close to spending $50,000 on a commission since arriving at Notre Dame — but she hopes to.

“We’re not there quite yet,” she says, “but we’re working on it.”

Jeremy D. Bonfiglio is a South Bend-based freelance writer and the staff features writer for The Herald-Palladium of St. Joseph, Michigan.