We all know about bad babysitters. They talk on the phone all night, raid the refrigerator and invite their friends over. What would horror movies and urban legends be without these irresponsible teens?

But what if you had the worst babysitter ever? What if Death itself, the infamous Grim Reaper, showed up on your front porch, scythe and all, and your parents went out to dinner anyway?

Devi Snively, a Notre Dame anthropologist, was captivated by this odd scenario. Can Death make a good babysitter? Can Death, perhaps, even earn a decent tip?

Snively will present her take on these and other questions in May. That’s when her newest short film, Death in Charge, will debut in Los Angeles. Snively is busy logging 14-hour days now financing and producing the film as part of the American Film Institute’s Directing Workshop for Women. She’s one of just eight women to receive this honor, which puts promising female directors through an intense three-week training workshop and several months of pre-production work, shooting, editing, post-production editing and marketing, with the ultimate goal of creating a professional short film.

For Snively, the film institute honor is just the latest success story of Deviant Pictures, the Mishawaka, Indiana-based film studio she runs alongside her husband, fellow Notre Dame anthropology professor Agustin Fuentes. It’s also Snively’s first chance to work with an actual budget. The film institute has provided Snively with $5,000, and she is allowed to raise an additional $20,000 to make the film.

“This is a film that we can’t make for $100 and in a single weekend like we usually do,” Snively says. “I decided that it was time for me to find out if I was ready to be accepted by the big boys or, in this case, the big girls.”

The film institute honor, and the short movie it helps Snively produce, may mean Deviant Pictures is on the verge of bigger things. For the Notre Dame professors, it means a chance to share their unique storytelling skills with a larger audience, a chance to show that not all horror movies have to be grim.

Snively, the studio’s director and screenwriter, and Fuentes, its producer, have collaborated on their low-budget films since founding Deviant Pictures more than four years ago. The couple’s short movies—which run anywhere from seven to 16 minutes long—have screened at more than 80 film festivals across the country, nabbing several awards at these festivals.

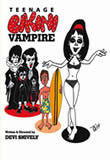

Deviant’s films have different distribution deals. Some may be ordered directly from Deviant’s website. Others, such as Teenage Bikini Vampire, must be ordered from Troma Entertainment, which has included the short film on its The Best of TromaDance: Volume 4 DVD.

Art on the fringes

It may not seem like a natural leap for two anthropology professors to go from classroom lectures to making short horror films. For Fuentes, creating these films is just a unique take on what he already studies and teaches.

“There is a whole world out there of American art that lives on the fringes outside of the mainstream,” Fuentes says. “That world contains some incredible art, political activism and, yes, even hilarious B-movies. Working on these films helps me to keep tabs on pop trends and innovations on the fringes of standard pop society.”

Even before becoming independent filmmakers, Fuentes and Snively had led interesting lives. Fuentes is also a primatologist who chases monkeys across the globe. Snively has worked as a ballerina, Spanish translator, video-game writer, hair model, book editor and newspaper columnist. She also teaches one of the most popular classes at Notre Dame, Cultures of Fear, which focuses on horror films and their impact on society. It always has a waiting list.

The world of independent cinema is a challenging one. Making movies on tiny budgets calls for creativity. It also calls for clever scripts that can work around the fact that Snively and Fuentes can’t spend millions creating fire-belching demons or 50-foot monsters.

So Snively, who writes Deviant’s screenplays, focuses on tales that are not only gory but are also dark—sometimes extremely dark—comedies. For instance, there’s Bedwetter, a 9-minute musical romantic comedy about an otherwise happy couple who must overcome the bodily functions that threaten to tear them apart. Teenage Bikini Vampire‘s protagonist just wants to go to the beach with a boy she loves, something that presents obvious problems for a member of Dracula’s extended family. One of the main characters of Snively’s Confederate Zombie Massacre! would much rather tap dance than shoot undead Confederate soldiers.

Deviant’s films lighten the mood at festivals that can otherwise contain some decidedly grim work, says Wayne Clingman, organizer of the It Came from Lake Michigan film festival. Last year, Teenage Bikini Vampire helped Snively nab the festival’s Lizzie Borden Female Horror Director Award.

“All the judges who saw that film liked it,” Clingman says. “Usually you get someone doing the whole Simon Cowell thing and saying they didn’t like it. But not this time. . . . Some of the films we receive we don’t show because the content is so rough. This, though, was campy and funny.”

Budget blues

Money is always an issue with independent filmmakers, and the Deviant founders have become experts in stretching their limited funds. Any zombie movie needs at least some blood, gore or severed limbs. That’s where creativity again comes into play.

A bonus feature on the Confederate Zombie Massacre DVD shows Fuentes cooking a batch of slime for his undead soldiers. He does this in his own kitchen with nothing more than a microwave and a jug of Metamucil and water. He could have bought the same type of slime for $80 or so at a special-effects store. By whipping up the mixture on his own, he sets Deviant Pictures back only $8. With a micro-size budget, that small savings counts.

Last year, Fuentes and Snively filmed their first-ever full-length feature, Trippin’. Snively describes it as a spoof of the Friday the 13th movie franchise that featured an assembly line of bland teens murdered by a killer who sometimes wore a hockey mask.

Making Trippin’ turned out to be a bit of a horror film itself. The crew shot the movie in 16 days last August in the woods of Niles, Michigan, with cast and crew working 14- to 18-hour days nonstop. Because most filming took place at night—what kind of horror film features hours of bright sunlight?—actors and crew had to sleep during the day. So Snively and Fuentes blacked out the windows in their Mishawaka house, which had become the local flophouse.

“We were a frat for a couple of weeks,” Snively says. “It was fun, but I think everyone was glad to go to their own homes and sleep for a few days.”

Snively describes the shooting as one of the most intense experiences of her life. During the day, temperatures would rise to the upper-90s, and the crew’s members would take turns hosing off the actors between scenes with chilly water. In the evening, when most of the filming took place, the temperatures would dip into the 40s, not comfortable for actors who spent most of their time running around, as Snively puts it, “in their skivvies.”

“Somehow, we finished filming a couple of hours early,” Snively says. “I think it was at 3 in the morning on the last night when we held our wrap party. We were all sitting there freezing around a bonfire in the woods. We were miserable, but we all felt like a real family. We all celebrated.”

Snively and Fuentes are thrilled with the results, although they still are in post-production. During that process the couple works with composers and special-effects gurus to add the right sinister touch to their films. Snively also edits the films down to a manageable length.

For now Snively has dived into her latest work in Los Angeles. She’s living with the other female directors and has already formed friendships with them. There have been nights out for drinks, poker parties and, above all, support.

She has learned the main difference between shooting a film in Mishawaka and in Los Angeles: No one really cares if you’re making movies in Los Angeles.

“Making a film here isn’t special. Everyone here is making a film,” Snively says. “The people in the neighborhoods where we are filming are incredibly savvy. The minute they see cameras and lights, the neighbors pull out their leaf blowers. You have to bribe them to turn them off.”

And then there is the food. “We have to treat our cast and crew here like humans, not like what we do in other productions,” Snively says. “We can’t feed them Twinkies at 2 in the morning and say we’ve done our job.”

While Snively works on Death in Charge, Fuentes is searching for extra funding to handle the post-production work on Trippin’.

“This is the most difficult part of indie filmmaking,” Fuentes says. “We can do a lot for a little, but shooting the film is not the end. The majority of work actually takes place in post-production. I’m going to hit up some dentists. For some reason, I heard that dentists really like to support this kind of thing.”

Dan Rafter lives and works just outside Chicago. He’s written for such publications as The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Phoenix Magazine, Business 2.0 and BusinessWeek Online. _Deviant Picture’s website is at home.comcast.net/~deviantpix/tbvwebsitepage1.htm home.comcast.net/~deviantpix/tbvwebsitepage1.htm _.

Photo of Devi Snively and Agustin Fuentes by Matt Cashore