When the puck dropped last spring to determine the unsettled 1989 state championship between New Jersey high school hockey powers Delbarton and St. Joseph Regional, it was surrounded by the sticks of husbands and fathers who never thought they’d play the big game taken from them two decades earlier.

It was a moment they’d all awaited since the day when the much-anticipated contest was canceled because of a suspected measles outbreak. The teams were declared co-champions — a compromise that satisfied no one among a group of competitors which included future college and professional hockey players. After 21 years of disappointment, the men finally found themselves facing off against each other thanks to such sponsors as Gatorade Replay, a division of the sports drink giant dedicated to restaging classic matchups of high school rivals.

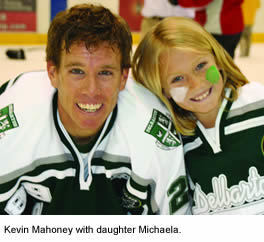

The event, dubbed the Frozen Flashback, drew players from coast to coast, including former Notre Dame lacrosse player Kevin Mahoney ’96, a freshman forward on the 1989 Delbarton team. For Mahoney, the survivor of a liver transplant in 2004, taking the ice with his old teammates was the kind of thing he had long doubted he would ever be able to do again.

A reality cross-check

Since age 9, Mahoney had battled what the doctors at Minnesota’s Mayo Clinic called cryptogenic cirrhosis. For no diagnosable reason, he and his parents had learned, his liver was only 10 to 15 percent functional and would likely one day fail. In addition, his enlarged spleen left him with greater vulnerability to rupture, an injury that Mahoney knew had claimed the life of a friend’s brother during a hockey game. As long as he took precautions — like wearing a protective cage around his spleen — Mahoney found support from his doctor and his parents to make the most of his body through sports. He excelled in hockey and lacrosse, and his skills in the latter sport led to a four-year college career that saw him score a healthy 35 goals for the Fighting Irish.

But one day in 2004, as a 30-year old husband and father of two living in Hawaii, he learned that life finally had caught up with his liver as a routine ride on his surfboard took more out of him than usual — and he couldn’t get it back.

Doctors said he needed a transplant soon. But before placing him on the depressingly long list of Americans in need of a new liver, they asked him if he knew anyone who might be willing to give him half of theirs. Although live donors account for only about a quarter of all liver transplants, they offer the greatest chance of success. That’s because the liver, along with the skin, is one of only two regenerative organs in the human body. To heal itself, a transplanted liver mainly needs time for the new cells to replace those lost from the operation and space for the transplanted organ to connect to the vital arteries around it.

Mahoney had always been close to his sister Maura, an emergency-room physician working in Arizona. Having dedicated her life to saving others, she was the first to raise her hand. “She always had a big interest in my health and my liver,” he says. “And she was pretty adamant about stepping up and getting tested first.”

The tests confirmed she was a perfect match. Within a month the surgery was successfully performed at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. Weeks later, Maura’s liver and blood levels had regained full capacity. Soon after, so did Kevin’s.

“She saved my life,” Mahoney says. “She’s obviously the most important person in my life.”

It would take longer to know if the change would last. To a body 30 years accustomed to weakened liver functionality, the new organ was an intruder that required a steady flow of steroids and immunosuppressants to convince the body to accept it as its own. Even then, full health requires thorough maintenance: biweekly blood work, pills twice a day and a regimented diet, including no booze — a condition he’d observed even at Notre Dame.

While Mahoney hoped for the best after the surgery, he also prepared for the worst, moving back to New Jersey for two years to live closer to family in case his new liver failed. He coached 7th and 8th grade hockey and varsity lacrosse at Delbarton and worked for its alumni association. Graduates of the all-boys prep school share a bond that is in some ways a high-school analogue for the way Notre Dame connects its alumni, which helps explain why it routinely sends five to 10 students to South Bend each year.

Mahoney credits that environment for reinvigorating his mental outlook. If ever a person could draw inspiration from something like a school motto, he found it in Delbarton’s Succisa virescit: Cut down, it grows back stronger.

“I went back there in total shambles. It really allowed me to get a new start on life,” says Mahoney, who has since moved with his wife and children to Los Angeles, where he is an analyst for a global risk and insurance services firm.

The brief homecoming, however, also rekindled old regrets for having hung up his skates too soon.

“I loved playing lacrosse at ND, but hockey was my first love my entire life,” he says. “I always considered myself a hockey player playing lacrosse to get to ND.”

So when Mahoney got the call about the Frozen Flashback and the chance to suit up one more time for his alma mater, there was no talking him down.

Skating at full speed

Mahoney’s decision to play in the Frozen Flashback was another stand in a lifelong refusal to let his liver dictate the terms on which he’d live. Though it was a personal victory that his mother and doctor were afraid could turn Pyrrhic, Mahoney did his best to assure them there would be no open-ice hitting and that he’d play with the same protective cage he wore as a student-athlete at ND. He’d also have the same armor he wears everywhere he goes — the triune shield of the Mayo Clinic tattooed to his chest.

“It’s the greatest place in the world,” he says.

Mahoney needed three months of regular workouts to reclaim the skating legs that adult responsibility and transplant recovery had diminished years before. Meanwhile, his teammates back in Jersey already had a couple months’ head start.

“When everyone got the hockey bug back, we had too much respect for each other to show up half-ass,” he says.

But as the game approached, it took on a significance that trumped an unsettled sports score. As word spread from the local papers to The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, sponsorship swelled. New Jersey Governor Chris Christie agreed to award the state champion’s Tiffany & Co. trophy to the victor.

The game’s purpose grew along with the publicity. St. Joseph captain Scott Williams, whose mother is battling brain cancer, converted the growing national interest into a drive to raise money to fight the disease. His efforts got a boost from the National Hockey League’s Hockey Fights Cancer campaign, ultimately netting more than $300,000 through game proceeds and sponsorships. Embodying the cause were two teams of pediatric cancer patients who took the pregame ice alongside former NHL stars for the ceremonial puck-drop.

“That was one of the most special parts of the night,” Mahoney says. “A lot of guys on the team were dads. It could’ve been any one of us having to go through this.”

The moment was a vivid reminder of his struggles and the greater gift of life. Above all, that’s what the game represented for Mahoney.

When the real puck dropped, it uncorked more than two decades of bottled resentment between two squads that Mahoney says were probably better than they’d been in their youth. The game was physical, with scrappy play in front of the goals and on the walls — and even one skirmish.

“We wanted to win this thing,” Mahoney says. They wanted victory both for each other as teammates and, he admits, for their wives and children — including his youngest daughter, Maura, named for his lifesaving sister — most of whom were seeing this part of their hockey past for the first time.

Mahoney says he played a much bigger role than he would have the first go-around, skating on a regular line that didn’t give up a goal during its shift on the ice. He nearly scored one himself when his own shot hit the pipe.

“I definitely wanted that one back,” he says.

In the end, Delbarton held on for a 3-2 victory. Mahoney gives a lot of credit to one of the players whose suspected case of measles set the story in motion two decades before.

More important, the game forged a bond between old adversaries who realized their efforts produced a legacy that would extend far beyond the ice. Organizers have received a lot of queries from groups that see the Frozen Flashback as a fundraising model.

“All of us were a part of such a bigger thing that day,” Mahoney reflects. “Life is pretty amazing that something like this could happen.”

Tim Dougherty, who interned at this magazine, is a writer living in New York.