Editor’s note: In celebration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, on May 25, 2017, Notre Dame Magazine is publishing this selection from our Hesburgh Special Edition here at magazine.nd.edu. Print copies of the special edition are available; please visit our store for ordering information.

Before he was president of Notre Dame, before he appeared on the cover of Time magazine, before The Nation named him “the most influential cleric in America,” before he was chair of the U.S Civil Rights Commission or served as the Vatican’s representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency, before he became a confidant of presidents and a familiar of popes — before all that, he was a boy growing up in Syracuse, New York, who built model airplanes and crystal-radio sets, joined the Boy Scouts, played baseball in neighborhood pickup games, did well in his classes at Most Holy Rosary parish school, and was once suspended for playing hooky on the first day of pheasant season.

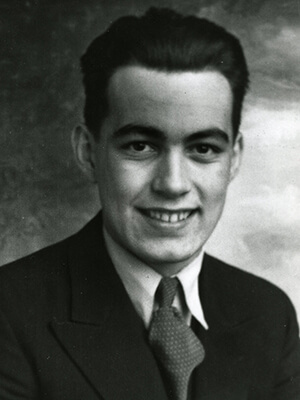

Born May 25, 1917, he was christened Theodore Martin Hesburgh, but mostly he was known as Ted. The second of five children, he had one older and two younger sisters, and about the time he was ready to give up on praying for a brother, he got one — just as he was preparing to leave home for the seminary. His parents, Theodore Bernard and Anne Marie Hesburgh, endowed him with a mixture of German and French heritage, with a touch of Irish through his mother’s side.

Something else he inherited from his mother was a keen sense of social justice. One day he came home from school to find her comforting a sobbing neighbor. Later his mother explained that she was Jewish in a neighborhood antagonistic to Jews and blacks.

“That’s what got me interested in civil rights,” he told an interviewer at the age of 88. “My mother used to use strong language on the neighbors, who just cut that woman when she’d be out pushing her buggy. No one would even say hello to her except my mother. That was my first encounter with prejudice.”

In those days, though, it was aviation, not civil rights, that intrigued him. Perhaps building model planes triggered it, but his fascination with flying really took wing the day a barnstorming pilot named Tex Perrin landed a World War I-era de Havilland biplane in a cornfield close to town, climbed down from the open cockpit, pushed back his flight goggles and offered rides to the locals for five bucks. Ten-year-old Ted Hesburgh and his pal Eddie Naughton scraped up the cash and spent 15 thrilling minutes circling over Syracuse and Onondaga Lake. And they were hooked.

But a different career goal was to trump aviation. “I never thought of anything else but becoming a priest,” Hesburgh told an interviewer in 2005. That goal was reinforced when his family sent him to New York City to see a cousin ordained in Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. He already was a daily communicant when he had an encounter with a priest who visited the parish as part of a mission team. Upon learning that the young Hesburgh was thinking of the priesthood, the Holy Cross father paid a visit to the family home. What followed is a story Hesburgh would tell often in later years:

“He came out to see my mother, and he said, ‘Your son, I think, may be a priest some day, and that would be a great blessing.’ And she said, ‘It certainly would.’ He said, ‘We’ve got a prep seminary out at Notre Dame; why don’t you send him out there for high school?’ She said no. The priest said, ‘If he doesn’t, he might lose his vocation.’ And she said, ‘If he grows up in a Christian family and he goes to Mass and Communion every day and attends a Catholic high school with the nuns and he loses his vocation, I’ll tell you something, Father, he doesn’t have one.’ And that was the end of that.”

Soon thereafter the boy’s confessor reassured him that his mother was absolutely right and he ought to have a normal adolescent experience: have dates, go to dances, live a full social life. During high school he held the predictable teen-year jobs: mowing lawns, delivering newspapers, working on the school paper. With three sisters in the household he could hardly avoid learning to dance, and as he matured he grew to be Hollywood-handsome. One classmate, Mary Eleanor Kelley, especially caught his fancy, but it never got serious. When his school mounted a three-hour-long production of the Passion, Ted Hesburgh played the role of Christ.

At graduation, he ranked third in his class. He might have been first if he hadn’t been unenthusiastic about the sciences. The night before he left Syracuse for Notre Dame and the seminary, he recalled, “my high school came out to see me off, and I think I kissed 35 girls goodbye.”

NOTRE DAME

His parents never put pressure on him to enter the priesthood, he said, but where he was headed was taken for granted by his high school classmates. He turned down a scholarship to Niagara University to enter the Holy Cross seminary, and in September 1934, in a borrowed Essex (a more reliable car than the beat-up Chevy the family owned), Ted Hesburgh, his mother, his father and his older sister, Mary Monica, set out for Indiana.

“We drove up to the seminary,” he later recalled, “and I said, ‘I’m here,’ and the superior said, ‘We’re not taking in new seminarians until Monday.’ This was Saturday, and we didn’t have any money, so we had to go downtown and find what today they call bed-and-breakfasts. For five bucks we got a couple of rooms. We had a rather scanty dinner that night, and then we came out Monday morning and I checked in.”

When his family drove away, he later recalled, “It was my lowest moment. I just felt abandoned in this place I’d never been before. For one month I never unlocked my trunk because I didn’t know whether I’d stay.” Seminarians in those days were not allowed to go home for Christmas or Easter. Not until the end of June would they visit their families for a couple of weeks before coming right back to the novitiate. Eventually the homesickness subsided. “Maybe,” he mused years later, “that was the price I paid for having a good family.”

Postulants lived in Holy Cross Seminary, later known as Holy Cross Hall. Although they were enrolled in the University, many of their classes were taught in the seminary and they weren’t heavily involved in University life. They did attend football and basketball games. In the first football game Hesburgh watched, the Irish lost to Texas.

His favorite course that year was Philosophy of Literature, taught by Father Leo L. Ward. “It was probably the best class I had at Notre Dame,” he told then-associate vice president Richard Conklin ’59M.A. years later during an oral-history taping. He earned a grade in the upper 90s, but, more importantly, he took to heart a bit of advice from Father Ward, who chided him: “You never use a simple word if it’s possible to use a polysyllabic one. If you don’t learn to simplify your style, you’ll wind up being a pompous ass.”

He spent the second seminary year in the novitiate, which was located on a farm in Rolling Prairie, Indiana, a few miles west of campus. Hesburgh described that time as “like boot camp, only worse. We had to keep silence except for one hour after lunch and one hour after dinner. We did all the farm work on the 600-acre farm, which was run down, and we had to bring it back to productivity. But I had a great master novice and spiritual adviser, Father Kerndt Healy.”

In 1936 the seminarians were back on campus as sophomores, and at the end of that academic year they filed through the Sacred Heart basement chapel for their junior-year obediences. Hesburgh assumed he would continue studying at Notre Dame, but when he opened his obedience he found he’d been assigned to study in Rome.

In a short biography of Hesburgh published in 1989, the late Professor Thomas Stritch explained: “Once in the Philosophy department of the seminary [Hesburgh] quickly caught the attention of his teachers, who decided to send him to Rome to give him the best education it was then thought a priest could have. It was the custom of the Holy Cross community to send their best and brightest there.”

ROME

Hesburgh and one classmate paid $90 each for passage aboard a French ship. In Rome they embarked on studies in philosophy and theology, a process scheduled to take eight years. The international Holy Cross student contingent in Rome numbered fewer than a dozen and lived in a small house where prayers and conversation were held in French, while classes were conducted in Latin.

Fortunately, Hesburgh had taken three years of French and four of Latin in high school. A natural linguist, he soon was fluent in both languages. He picked up Italian on his own, and during class breaks he spent time with a Spanish friend and became adept at understanding that language.

- More from the Father Hesburgh Special Edition

- The Strength of Leadership

- The Endless Conversation

- The Long Twilight

- The Right Side of the Road

To round out the language skills that would serve him well in his globetrotting presidential years, he spent two summer months at a Holy Cross house in the Tyrol, where he concentrated on learning German. His regimen that summer: “I read the whole New Testament in German, and I learned all the irregular verbs and I spent a couple of hours every day studying German vocabulary and grammar.”

He completed the baccalaureate in philosophy in 1939 and took his final vows that August, with the expectation that he would stay in Rome for five or six more years. A month later Hitler invaded Poland, and Europe careered toward World War II. The seminarians, despite not being allowed to listen to the radio or read newspapers, could not help being caught up in the turmoil of the times.

“Rome in those days was pretty wild,” he told an interviewer six decades later. “Mussolini invited Hitler down to Rome, and I remember the day another student was looking out the window and said, ‘Hey, Ted, come over here; Mussolini’s coming by in an open car with Hitler.’ I said, ‘I wouldn’t walk 10 feet to see that bum.’ Now that I’m older, I kinda wish I’d seen him, but in those days principle was very strong. It was a very exciting time. The Italians were getting all geared up for war, Mussolini was spouting, and the Italians had a famous squad [of troops] who wore plumed hats and always ran rather than walked.”

As war fever escalated, the seminarians found ways to keep up with events. Despite the ban on radios in the house, the superior finally gave in and bought one. He set it on the piano in the recreation room but refused to turn it on until the superior general of the order returned to Rome from Bangladesh and said, as Hesburgh recalled it: “There’s some very historical things going on, and you’ve got a radio sitting on the piano. Turn on the news.”

Newspapers also were forbidden, but the seminarians’ daily route to classes took them past the offices of Il Messaggero, where the day’s edition was posted on the building walls. “We could stop and pick up on what was happening,” Hesburgh said.

In May 1940, as Hesburgh was nearing the end of his first year of theology, the U.S. consul in Rome walked into the classroom one day and said: “Those of you who are Americans, unless you want to spend the war in Italy, the last boat is leaving Genoa a week from today.” Hesburgh decided he’d better be on it.

The ship was the S.S. Manhattan, and an episode on the dock before he boarded made him glad to have fluency in several languages. “I saw a woman on the dock with three little kids, and she was in obvious distress,” he recalled in an interview. “I said, ‘Madame, are you American?’ and she said, ‘Yes, I’m the wife of the American ambassador to France, and we just got out of Paris as the Germans were closing in. I want to send a telegram to my husband back in Paris, but the man here who takes radiograms doesn’t know any French or English and I don’t know Italian.’ I said, ‘Give me your telegram, and I’ll put it in Italian.’ So I wrote an Italian radiogram to her husband saying she’d arrived safely in Genoa and was getting aboard the Manhattan.”

Nazi U-boats were prowling the Atlantic that summer, and there were rumors that they might target American ships, so the Manhattan hugged the coast as far as Gibraltar, then made a beeline for Florida before turning north along the U.S. coast. The ship reached New York just as Mussolini declared war on France. Hesburgh remembers the ship’s loudspeaker relaying President Roosevelt’s outraged reaction in a radio address: “He was really giving it to Mussolini for being a coward and jumping on the French when they were under siege.”

FDR delivered that speech at the University of Virginia, intoning: “On this tenth day of June, 1940, the hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor.”

WARTIME WASHINGTON

Hesburgh was allowed 10 days at home with his family, whom he hadn’t seen in three years. His next assignment was Washington, D.C., but first he reported to a Holy Cross summer camp in Maryland and renewed an acquaintance with Charles Sheedy, a seminarian who would become one of his closest friends. Hesburgh was assigned to teach French to the seminarians at the camp.

“On the first day,” he recalled years later, “I said, ‘Today we’re gonna learn 10,000 French words.’ They all gasped, and I said, ‘You’ve gotta remember that French was derived from Latin, and you guys all know Latin. A French word like verite, truth, comes from veritas in Latin. With that one rule, you now know 10,000 French words.’”

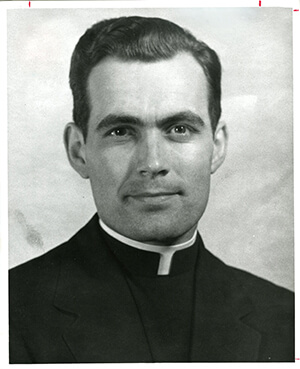

By December 1941, when the United States entered its two-theater war, Ted Hesburgh was deep in theology studies at Holy Cross College in Washington, where he spent three years before returning to Notre Dame for his ordination on June 24, 1943, in Sacred Heart Church. Then it was back to Washington for a doctorate in theology that he whipped through in two years instead of the usual three.

During his years in the wartime capital, he and Charlie Sheedy teamed up to plug a gap in the religious literature available to U.S. servicemen and women. For starters, Hesburgh translated a booklet the French army had used for Catholics in service.

“Charlie said, ‘That’s too French; we’ve got to do something more American.’ So we put out a booklet called For God and Country, which became so popular they published over three million copies. And my sister was in the WAVES, so I wrote another booklet, Letters to Service Women, and they published more of those than there were women in the service.”

These publishing ventures grew into a series of religious publications called Contact. “Every month we’d get out a Contact on some subject like swearing or purity or prayer,” Hesburgh recalled, “and it turned out to be the only Catholic literature chaplains had to give to soldiers. The National Catholic Community Service [one of the units under the USO umbrella] published a couple hundred thousand of these booklets at a time, and they got dropped by parachute to camps out in the Pacific and through Europe.”

At the time of his ordination, he had pleaded with his superiors to let him join the Navy as a chaplain, but they insisted he earn the doctorate. When he completed that assignment in record time, he asked again, because “I very much wanted to be a Navy chaplain on an aircraft carrier.”

VETVILLE CHAPLAIN

Summer 1945: The war in Europe was over and the war in the Pacific soon would be. Instead of being allowed to join the Navy, he was ordered back to campus. Referring to the Navy’s wartime V-12 program on campus, the provincial told him, “We’ve got more Navy at Notre Dame than any ship in the Pacific,” as Hesburgh recalled the conversation. “Having a vow of obedience, I pulled up my socks and came back.” Two days after reaching campus he was in the classroom teaching six sections of theology classes.

It wasn’t long before he found himself also serving as a sort of military chaplain for the wave of veterans streaming into college under the G.I. Bill of Rights. He was a prefect in Badin Hall, where he shared the third floor with 80 returned vets. When the hall lights were shut off at 11 o’clock, his room, 333, quickly filled with students who wanted to continue studying. He did his best to accommodate them.

“I wound up sitting on the floor some nights,” he said. A few disabled vets were in wheelchairs, but their classmates, Hesburgh said, “took good care of that. If they had class in the Main Building, they’d wheel the chair to the bottom of the steps, and one of these burly veterans would each take a wheel and carry the chair up the steps. And then down again after class. Nobody ever asked. It just happened.”

The veterans, he wrote in his book, God, Country, Notre Dame, “were older men with different problems than those of the so-called traditional students. I thought these men might better adjust to campus life if they had some kind of organization they could call their own, and so I started the Notre Dame Veterans Club for the first 70 or 80 veterans on campus and became its chaplain.” Within a year or so, 73 percent of the whole student body were ex-G.I.s, and the club was closed down. “It seemed rather silly to have a club that everybody belonged to,” he wrote.

Some of the veterans were married and found themselves on a campus ill-prepared to accommodate family living. Makeshift married housing was slapped together on the northeast edge of the campus for 116 couples who formed an instant community known as Vetville. “Since nobody was taking care of them, I went over and became their chaplain,” Hesburgh said in 2005. “They were all brand new marriages made during the war. Many of the girls weren’t Catholic. I set up an instruction class, and I’d have six or seven sign up for it.”

The Vetville residents established a village government, elected a mayor and published a newspaper initially called the Vetville News and then, variously, the Vet Gazette, the Vetville Herald, the Villager and Ye Olde Vetville Herald. Hesburgh made arrangements with a local hospital to provide pregnant wives with pre-delivery and postnatal care for a package price of $75. “I had a lot of baptisms,” he said, “because they were constantly having babies.” For the married students who couldn’t squeeze into Vetville, he drew up a list of decent in-town rentals.

Some of the wives were inexperienced in gestational matters, and in God, Country, Notre Dame he wrote of the time he had to explain to one young wife why she was sick every morning. “She had no idea it was because she was pregnant. A celibate priest had to tell her.” Joe Dillon ’44, ’49J.D., who was president of the campus veterans’ club, told of Hesburgh discovering another pregnant wife on her hands and knees scrubbing her apartment floor one day; he took over the chore and finished it for her.

Hesburgh wheedled the U.S. General Services Administration out of a large surplus chapel from a Saint Louis Army camp and had it transformed into a recreation hall. Sixty to 70 couples would show up there for Saturday night dances. Admission cost a quarter and included a glass of Coke.

“Women’s styles changed after the war,” Hesburgh reminisced in 2005, “and the skirts, which had been quite high, went way down. Only two or three of the wives were wealthy enough to afford a new skirt, so I had a rule: If you showed up with a full skirt, you had to go back and change it be-cause all the other girls would be jealous.”

His Vetville experiences had a carryover in the classroom. “I’d learned so much about marriage and what made it work or not work that I started a class in marriage when I became chairman of the religion department,” he said. That class got so popular it had to be moved into Washington Hall. Summing up those years in his later life, Hesburgh mused: “Maybe the vow of obedience worked out. I was working with veterans after all, and these were guys starting a new life — it was just a marvelous time.”

In his Hesburgh biography, Tom Stritch wrote of that anomalous era in pre-co-ed Notre Dame’s history: “For married vets, the university built a little village on the campus, by a happy coincidence where the Hesburgh Library now stands. In this odd ambiance of tight quarters, steamy kitchens, drying diapers, and hard study . . . Hesburgh flourished. He became confessor, babysitter, confidant, and friend to hundreds of these young people, and they in turn helped to form him into a warm, compassionate, tolerant, and sympathetic person.”

Not everybody was impressed by Hesburgh’s chaplaincy at the time, however, as he discovered one day when Father J. Hugh O’Donnell, CSC, who was president of Notre Dame from 1940 to ’46, stopped him after prayers in Corby Hall and demanded to know who put him in charge of Vetville. He recalled the incident in a 2005 interview: “I guess some of my non-friends around here were griping that I was doing all this work over there. I said ‘Father President, if it doesn’t please you, I’m perfectly willing to stop.’ And he just went harrumph and walked away.”

In 1948, when the veterans’ surge was waning, Hesburgh moved out of Badin to become the first rector of Farley Hall. Overseeing a collection of 330 “green freshmen” was not as much to his liking, and it wasn’t long before another assignment came along that he liked even less. Tom Stritch recalled the moment this way: “When . . . the then-president, Father John J. Cavanaugh, approached him to join the administration as his executive vice-president, Hesburgh’s hackles bristled. He wanted no part of official discipline and officious policing.”

But an obedience was an obedience, Hesburgh shrugged in a 2005 interview: “Father Cavanaugh was halfway through his six-year term. I guess he knew he’d better get somebody ready to take his place. I had just turned 32 when I took on that job, and I asked him, what does it mean to be executive vice president? He said, ‘Well, we have five vice presidents, and you’re the vice president in charge of vice presidents. You’ve got to write the articles of administration for what they all do.’”

In January 1952, an ailing Cavanaugh went to Florida for a rest, leaving Hesburgh to “take care of things.” Six months later, Cavanaugh’s term ended. There was no search for a successor and the choice was made by the religious community; that was the way of things in those days. At the end of the annual priests’ retreat that summer, Father Ted was handed a new “obedience.” He was to be president of the University of Notre Dame.

Outside Sacred Heart church afterward, Cavanaugh handed his successor the key to the presidential office and warned that he’d find the desk smothered in unanswered mail. He also announced he was leaving campus that evening on the 7 o’clock train to New York but had promised the Christian Family Movement he’d give them a talk at 7:30 in the veterans’ recreation hall.

His parting words to the new president: “You can do that for me.”

Walt Collins was editor of Notre Dame Magazine from 1983 until 1995.