The Christmas seasons of World War II were anything but normal at Notre Dame. As usual, students rushed to classrooms and looked forward to the holidays, but they could not have helped but notice the enhanced military presence occasioned by the war with Adolph Hitler’s Germany and Emperor Hirohito’s Japan. Hundreds of uniformed midshipmen, completing their pre-war training at Notre Dame through an arrangement between the University and the United States Navy, jostled for space on the narrow pathways that connected classroom buildings with student dormitories.

By Christmas 1944, the fourth since the Navy’s encampment began in September 1941, young officers-to-be had become as much a fixture of student life as football games and pep rallies, but they also reminded the rest of the student body that, despite the religious significance and sentimentality of the season, war, violence and bloodshed were an inescapable reality of the world beyond campus.

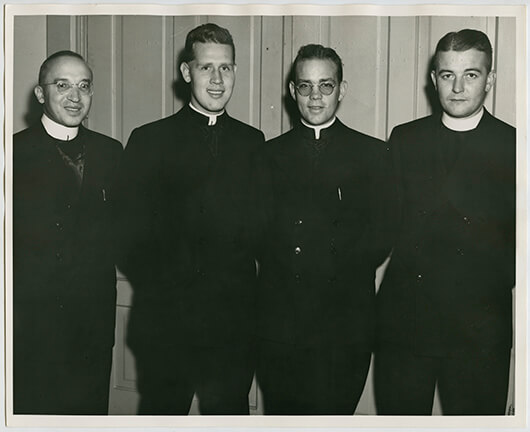

Back at Notre Dame in April 1945 after more than three years in confinement are (left to right) Brother Theodore Kapes, CSC, Brother Rex Hennel, CSC, ’41 Father Jerome Lawyer, CSC, ’35 and Father Robert McKee, CSC, ’36. Photograph from the Archives of the University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana.

Back at Notre Dame in April 1945 after more than three years in confinement are (left to right) Brother Theodore Kapes, CSC, Brother Rex Hennel, CSC, ’41 Father Jerome Lawyer, CSC, ’35 and Father Robert McKee, CSC, ’36. Photograph from the Archives of the University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana.

Students were not the only members of the Notre Dame community touched by the conflict. Along with his Holy Cross brethren at the University, Father Thomas A. Steiner, CSC, the congregation’s provincial superior, celebrated Christmas with Midnight Mass in Sacred Heart Church, a building resplendent with religious paintings, icons and statues. Many people entered the church through its eastern Memorial Door, beneath the inscription, “God, Country, Notre Dame,” honoring alumni and students killed in World War I. Steiner’s thoughts, though, most likely centered on those alumni who had perished in this new war, as well as on the 29 chaplains from Notre Dame and six Holy Cross missionaries then living in battle zones around the globe.

As provincial, Steiner managed the day-to-day activities of the community in the U.S. and approved or denied all requests from Holy Cross priests and religious to serve overseas. From their distant posts these men sent him frequent letters in which they explained their duties, described battlefield conditions and inquired about the latest events back home at Notre Dame.

A sense of family and purpose animated the priests. “Our chaplains are pretty well scattered over the face of the earth,” Steiner wrote that year. “They are on all fronts except the Russian front. When they all get back there will be no country and no island that some one of them have not been on, or at least, have had a close look at.”

His concern for their welfare mirrored that of millions of mothers and fathers whose sons had dropped the implements of their peacetime labors and studies to lift the weapons of war. “The war is becoming more serious every day,” he wrote to one chaplain ready to leave for Europe, “so you may expect to move at any time on short notice. We hope and pray that all will go well with you. Keep up your courage, and frequently renew your confidence in Divine Providence. You are doing God’s work.”

For those chaplains serving in Europe and the Pacific, Christmas 1944 brought bittersweet emotions. While moved with the familiar Christmas spirit, they were acutely aware of the grim contrast between the celebration of the birth of the Prince of Peace and the violence that so fundamentally clashed with their religious and moral principles.

Their letters reveal how that contrast made honoring the holy day more imperative, deepening their conviction that the Christmas message stood as the antidote for what then ailed the world. Whether harsh or merely humble, the conditions under which they would have to celebrate the feast surely paled before the splendor they could imagine back at Notre Dame.

In Europe, Father Joseph D. Barry, CSC, ’29 spent the days leading up to Christmas in snow-covered foxholes, counseling soldiers of his Army unit, the 157th Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division. Not only did the intense fighting in the Vosges Mountains of eastern France spike a rise in battle fatigue, but the soldiers also had to cope with being away from loved ones for a second consecutive Christmas. Any young man who entered the military during those years knew that his tour of duty would not end until the war did, but Barry’s soldiers — to whom he always referred as his “boys” or “lads” in letters home — had engaged in near-constant combat since landing on Sicily 18 months earlier.

In his monthly chaplain report to Army superiors, Barry recorded more instances of self-inflicted wounds and desertions than ever. He often spoke to the men about leaning on their faith to help them through adversity, but they were tough words to sell to soldiers who had been in combat for so long. These men had seen German mortars and bombs rip their friends apart. They were frightened, and they were weary.

That December, Barry, who had earned a reputation as a chaplain who could always be found at the front, dodging bullets and shells to bring religious comfort to terrified young men, wrote his close friend, Patricia Brehmer. He told her that despite what she read in the newspapers, those articles “do not tell half the story because you must be up front to get it and very few [correspondents] are there since Pyle took off for the States” — Ernie Pyle was the nation’s most beloved newspaper war correspondent.

Barry noted that rationing and shortages back home caused hardships, but asked that Brehmer and her friends take time to think of the boys overseas. “Do say an earnest prayer for the boys fighting along this western front. The boys have a word for it — ‘plenty rough.’ From the looks of things right now our Christmas will be a ‘scary’ one. These Heinies are fighting mad now that we are fighting in their homeland, in spite of the baloney of one Mr. Hitler.”

Following combat in Normandy in June 1944, Father Francis L. Sampson recites Last Rites over paratroopers killed in the bitter fighting. Photo from the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

Following combat in Normandy in June 1944, Father Francis L. Sampson recites Last Rites over paratroopers killed in the bitter fighting. Photo from the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

Father Francis L. Sampson ’37, a priest from the Diocese of Des Moines, Iowa, faced different tribulations as he and 400 American captives from the early days of the Battle of the Bulge continued their weary trek out of Belgium toward a German prison camp. Christmas Eve was normally a joyous occasion, but that day they marched until dark, trudging along without lunch or dinner, hoping merely to stay alive. On Christmas Day, Sampson’s group entered the German town of Prüm, where guards herded them into a large auditorium adorned with photographs of Hitler and other Nazi leaders. There they consumed their Christmas feast — half a boiled turnip, half a slice of bread and a cup of warm water.

The meager fare angered the captives. When they appeared ready to riot, Sampson, a paratrooper chaplain who had jumped into Normandy the previous June 6 with the 101st Airborne Division, became convinced that any resistance would be met with gunfire and death. He suggested to the American colonel in charge that he be permitted to conduct a brief Christmas service in hopes of quelling emotions. After leading the men in singing “Silent Night,” Sampson recited a prayer and spoke for 15 minutes, reminding the hushed captives that even in the midst of their predicament, Christ was with them.

In the Pacific Ocean on the other side of the world, after hearing confessions for three hours in the vast anchorage of Ulithi in the Caroline Islands, 1,500 miles southeast of the Philippines, Father Henry Heintskill, CSC, ’36 walked the deck of the escort carrier, USS Tulagi. Alone with his thoughts as a warm breeze fanned his face, Heintskill stared across miles of water so packed with ships that he mused he could walk to shore by stepping from one vessel to another. Each ship, he noticed, was blacked out to avoid detection from the occasional Japanese bomber.

As he continued his stroll, a lookout extended a Christmas greeting and the soft sounds of two sailors humming “Silent Night” drifted across the deck. The humming was “terribly off key but with feeling,” he wrote in a Christmas Eve letter to Father Steiner. “You somehow feel that tonight our lookouts are not the best in the world. Somehow you feel that even though they’re looking up toward the sky their eyes are staring off into the blackness back toward their homes.”

Heintskill’s thoughts also drifted homeward. “Somehow up here in the night it seems so very much like home. There’s no snow — but the night is the same — the stars are the same that the folks back home can see.”

Not far away, Father John M. Dupuis, CSC, ’31 fresh from the Pacific battlefields where he had accompanied the 4th Marine Division, barely had time to brush off the grime and dust of the front lines before resuming his sacramental duties. He was thankful for the rare opportunity to celebrate the holy day at a back base, not so much for his own needs, “but for the kids themselves. It is going to be hard for them away from home and out of the States. I rather think there will be many a homesick Marine this coming Christmas.” He told Steiner that he would be preaching to 1,500 Marines at a Midnight Mass held in an outdoor theater.

There were homesick civilians and religious in the Philippines as well. Brother Rex Hennel, CSC, ’41 was one of six Holy Cross missionaries from Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s — two priests, two brothers and two nuns — confined in Philippine prison camps since December 1941, when the onset of war had interrupted their journey to their mission in India. As Christmas drew nearer, Hennel noticed deepening depression among the residents of the Los Baños Internment Camp near Manila. They were understandably discouraged. Most were spending their third Christmas as prisoners of the Japanese — cut off from family, friends and all that was familiar and welcome.

They struggled against suffocating odds to make the holiday memorable. On Christmas Eve afternoon, Jesuit seminarians staged a holiday program of songs and skits that cut through the melancholy and offset the anticipated Christmas breakfast of rice and corn mash. Most of the camp joined them in crooning both lighthearted tunes that produced laughter and sentimental favorites that led to tears. The words they sang to the tune of Bing Crosby’s popular “White Christmas” became an instant hit thanks to lyrics that, not surprisingly, focused on food:

I’m dreaming of a fudge sundae

That’s in a store in Baltimore!

Where the fountain glistens

And Daddy listens

When children say I’ll have some more.

Another, performed to the tune of “She’ll Be Coming ’Round the Mountain,” pointed to their greatest Christmas wish.

And we will be free forever when they come

Oh we will be free forever when they come

And in spite of all our labors

We’ll be glad that we were neighbors

We’ll be glad that we’ve been neighbors when they come.

Midnight Mass in the barracks chapel capped an unforgettable day. A Nativity scene featured the Holy Family and shepherds sculpted from sand by one of the Holy Cross brothers. The priests concelebrated Mass, and Sisters Mary Olivette, CSC, and Mary Caecilius, CSC, led the multifaith congregation in Christmas carols and hymns. “So the Providence of God gave us consolation when we most needed it,” wrote Sister Mary Olivette.

Their families were thousands of miles away and they lived in squalor, but they were overjoyed by what they considered the happiest of Christmases. “Sitting quietly before the Blessed Sacrament with the whole of my possessions on me — a pair of shorts and a pair of wooden sandals — I fully realized I had all that I needed,” wrote Hennel.

War would not end for Notre Dame’s chaplains in Europe until Nazi Germany was defeated five months after Christmas, and would persist an additional three months for those mired in the Pacific. Like Hennel, however, the chaplains realized that in bringing the comforts of their faith to others in dire conditions, they obtained a clearer understanding of what was truly significant. Christmas 1944, a time when they lacked even the simplest of amenities, had powerfully underscored that point.

John Wukovits is a World War II historian who has written several books about that conflict. This piece is adapted from his forthcoming book, Soldiers of a Different Cloth: Notre Dame Religious in World War II, which Notre Dame Press will publish in August 2018.