Remember those connect-the-dots coloring books we used to get as kids? When I was 10 or so, my brother Charlie gave me a set of connect-the-dots sewing cards. Each one was made of stiff cardboard, and you were supposed to use the thick needle and yarn to sew from dot to dot. The concept was the same as the coloring books: from an assortment of apparently random dots on a blank page, the outline of a familiar object would emerge.

My most indelible memory of this gift, however, is the outrage I felt when I opened it. I can’t remember why it made me so mad. Looking back on that Christmas day from the vantage of my present self, I think I know. At age 10, every kid thinks she knows how to connect the dots. No stupid coloring book or sewing kit can do it half as well as a fifth grader. Except that it is actually really hard.

Connecting the dots is what I’ve spent my life trying to do, as a teacher and scholar and more recently as a mentor of kids from the west side of South Bend. The payoff is great when you start to see how dots — people, events, ideas, economics and even the past — hook up to make meaning.

It can also be painful. Living in the United States these days is to hear stories of violence every day. Just the other night in South Bend a woman was badly beaten by a robber apparently frustrated that she had no cash on hand. Her two young daughters watched and screamed and cried, and were taken in by the neighborhood women who are keeping mum.

The silence swaddling that violence makes sense, I think, if you connect the dots. It crystallizes several factors that exist in certain neighborhoods of South Bend or any U.S. city: poverty, hopelessness, unemployment, drug abuse, gangs, under-resourced police and, especially, the growing number of armed people roaming city streets.

The fact that a single victim might happen to be a woman may be incidental, a random dot in the tapestry of urban blight. The fact that her fearful neighbor is a woman is less random.

Women have for centuries stood witness to violence and have long been afraid to speak up for fear of reprisals. It’s not because we’re meek or accepting but because we have other people to think of, mainly our children. We know that those women who have spoken up have not always fared so well, nor have their families.

Just connect the dots as you think about all the nameless women who spoke out against abuse and who lived to regret it, in Chile, Rwanda or Sudan, in the Middle East, Afghanistan or East Asia. Go further back in time and remember the suffragists, many of whom were shamed into silence or starved into submission.

As a professor of French, I think about the activists of the 19th century, such as the so-called Vésuviennes (known for wearing culottes) or the pétroleuses of the Paris Commune, whose outrage over the French government’s refusal to honor republican principles materialized in social movements with an outrageously high number of civilian dead. Many of the dead were women, and their kids were orphaned as a result.

I think about Marie-Jeanne Roland, the wife of a high-ranking 18th century government minister and an outspoken politico, who may well have regretted her involvement with the revolutionary cause of 1789-92 when, from the foot of the guillotine during the Reign of Terror, she realized her daughter and sole survivor would pay the price.

Speaking up is hard to do. Compassion is fleeting, and in the end you’re all alone. You only have to connect the dots to see this.

I connected other dots this past summer, working on the Amnesty International exhibit “DIGNITY: Poverty and Human Rights.” The exhibit, making its U.S. debut at Notre Dame’s Snite Museum of Art now through March 2011, is the visual centerpiece of our contribution to a worldwide commemoration of the 18th century Swiss philosopher and writer Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). We at Notre Dame are focusing on Rousseau’s role as a pioneer of humanitarian thought.

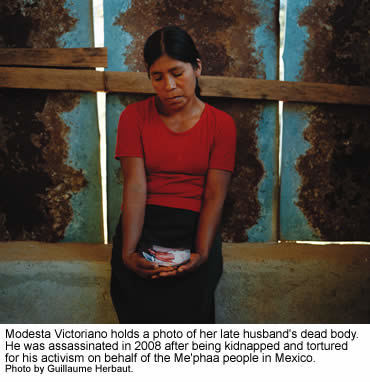

The DIGNITY exhibit, unveiled in Paris in 2010, delivers a jolt to viewers in its portraits of what poverty looks and feels like from five countries: Egypt, India, Mexico, Nigeria and Macedonia. The stories take on different forms depending on the people’s situations. The portraits of Me’phaa people from Mexico frame the most basic human wish: an end to the ethnic persecution and murders that have devastated their numbers. Two photos show a woman and a small girl holding photos of their dead menfolk — a brother, a father. Two other women speak out from portraits of despair, telling of the nightmares they still see in their mind’s eye of the soldiers who repeatedly raped them. They said they were afraid to speak for a long time, and they’re still afraid now. But the risk is worth it, they say, if it will end the violence.

By bringing this exhibit to the United States, people like me — academics and art museum professionals with a political conscience — hope to raise awareness about such atrocities. Each haunting section calls for observers to respond through words and support. It feels good to be involved in a cause like this. It feels good to help mobilize some action that may make an impact. Yet the images and histories give me pause. Although I admire the women who spoke out from Mexico or Macedonia, I now worry about them. I wonder if they regretted bringing attention to themselves. I wonder if they are still alive, still able to work, to care for their families.

I also keep thinking about that nameless woman robbed and beaten in South Bend, her neighbors and the many others who’ve entered my mind during the planning for DIGNTY at Notre Dame. The dots seem to be converging. Human rights abuses that I once thought were far away are drawing near.

Julia Douthwaite is professor of French and Francophone Studies at Notre Dame. She is coordinating the launch of the Amnesty International DIGNITY exhibit touring the United States, beginning with its début this month at the Snite Museum of Art. Her most recent book is The Frankenstein of 1790 and Other Lost Chapters from Revolutionary France (forthcoming, University of Chicago Press, 2012).

See the Dignity@nd slide show.