A few years back, wandering through Houston’s Half Price Books, I came across The House with a Clock in Its Walls by John A. Bellairs ’59, a prolific creator of children’s and young readers’ books, and my classmate, mentor and best buddy during our undergraduate years at Notre Dame.

The young lady at the checkout counter was delighted. “He was my favorite writer when I was growing up,” she said.

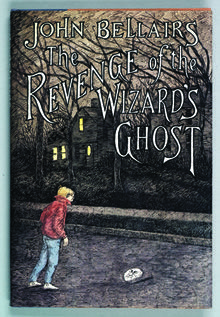

And well he might have been, for what young reader could resist titles like The Secret of the Underground Room, The Lamp from the Warlock’s Tomb or The Curse of the Blue Figurine?

Growing up fat, pimpled and homely in Marshall, Michigan, a hopeless klutz on the playing field and an admitted trembling coward, Bellairs spent his childhood and adolescence the target of other boys’ incessant hectoring, a perennial victim of the sort of bully who nowadays forms the cynosure of educational reformers. None of those self-aggrandizing childhood taunters, I daresay, ever went on to graduate magna cum laude from Notre Dame, write a best-seller, or have a historical plaque or a guided walk for tourists dedicated to their memory in their hometown.

Seizing the only refuge from nonstop teasing he could find, he retreated early into books, becoming an avid and voracious reader, devouring literature with a ravenous appetite and an encyclopedic memory that made him, by the time he entered Notre Dame as a freshman in the fall of 1955, “a bottomless pit of useless information” — his own not wholly inaccurate description of himself.

From him, to give only two proofs of that characterization, I learned how to chant — in Arabic — “There is no god but Allah, and Mohammed is his prophet,” as well as the correct spelling and pronunciation of Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg, the New England site of the longest place-name in the United States, and otherwise known as Lake Webster, along with a famous translation of that gigantic polysynthetic word-sentence, “You fish on your side, I fish on my side, and nobody fishes in the middle.”

Small wonder that he was named to Notre Dame’s G.E. College Bowl team, hosted back then by Betty White’s husband Allen Ludden — selected along with our classmates Phil Gibson, Andrew Connelly, Brian Moran and Tom Banchoff — or that in answer to one question he reeled off a dozen or so lines from Chaucer’s prologue to the Canterbury Tales in fluent Middle English.

He loved to play with the English language, throwing an original twist on clichés — as in his rendering of a particularly easy task as “A piece of park, a walk in the cake.”

Then as now a hit-the-books school like Stanford and Duke, Notre Dame was for him and me a magical vacationland where we both managed to earn consistently high grades while devouring pizza and movies, listening to Al Myers’ huge classical record collection, and spending hours in Bellairs’ disheveled room in Sorin playing chess, pinochle and Scrabble, meanwhile dissecting every aspect of the liberal arts, deep intellectual speculations endlessly enlivened by Bellairs’ boisterously funny asides.

In games he had no hesitancy to cheat: in a chess game, when I felt the urge to run across the hall to the head, I had to break world landspeed records to get back before Bellairs rearranged the board in his favor. The only break I can recall in our daily gaming was the widespread campus outbreak of Asian flu in late 1957, which landed me in the infirmary and rendered him, by his sworn account, bloated and floating about the room until his bellybutton grazed the ceiling.

We managed all this time free of tedious study by virtue of an educational technique Bellairs was generous enough to share with me early on. “The time to cram a subject,” he said, “is not at the end of the course, the night before finals, when you should be taking in a movie. Cram at the outset, right after registration.”

So after signing up, we would hit the bookstore, buy a couple of worthy books on each subject we’d registered for, blaze through them over the weekend, and sail into class on the first day armed with erudite facts and ready to dazzle the professor.

Our favorite eatery was Febbo’s Pizzeria, where two or three of the Febbo parrots (the ultimate cause of Febbo’s downfall at the hands of horrified health authorities) would perch on the edge of the pool table or the shuffleboard to watch and squawk while we awaited Mama Febbo’s incomparable sausage pizza. A past master of the English language, Bellairs would often interrupt his sentence during our long walks to Febbo’s with an hilarious parenthetical, picking up the original sentence a mile and a half later exactly where he had left it off.

He was an avid disciple of the campus then-guru, Frank O’Malley, and as an English Lit major Bellairs’ final exams were always of the essay type, a medium in which he could easily charm any instructor with his erudition and wit. He was ready at all times with a canny riposte, as on one occasion when he and I were suffering through an appalling student production of Romeo and Juliet at Washington Hall and I whispered to him, “The plot thickens.” Instantly he rejoined with “Yeth, it duth,” and later told me “I’ve been waiting for years to use that one.”

Assisting one of his professors by evaluating student essays, he was collapsed in helpless laughter one afternoon by a euphuistic freshman’s characterization of his family home, rhapsodizing about the beautiful scenery “that circumnavigated the house.”

We used to walk around the lakes on fine days, often reflecting ruefully on what we knew were halcyon days at Notre Dame, inevitably to be followed after graduation by the drudgery of a 9-to-5 job with meager two-week vacations. Meanwhile he honed his writing skills, writing a regular humor column for the student magazine Scholastic.

His vast reading and entertaining conversations had given him a huge repertory of favorite comical anecdotes — solid truth or wanton fantasy — including the tale of the young man who approached Mozart asking how to write a symphony. When Mozart advised starting with a few ballads before tackling something so complex as a symphony, the young man protested, “But Maestro, you were writing symphonies when you were only 10 years old.” To which Mozart replied, “Yes, but I didn’t have to ask anybody how.”

One of Bellairs’ favorite stories, beyond all doubt apocryphal, was that of the ultimate end of the imperial state crowns of Mexico, glittering remnants of the emperor Maximilian and his mad consort, Carlotta.

It seems that Napoleon III, among his many gifts to the infant University of Notre Dame, had bestowed upon the University the ill-fated monarchs’ bejeweled diadems. After reposing for decades in the dusty display cases of the now-defunct campus museum, the crowns had long ago been appropriated by unwitting campus drama enthusiasts for use on the stage of Washington Hall as Shakespearian props. But being found too garish for the willing suspension of disbelief, many of their jewels had been pried out and the precious metal painted with gilt. Eventually they had been discarded as junk, ultimately to become part of the landfill upon which Moreau Seminary is built.

Bellairs’ penchant for humor did not exclude the occasional practical joke. One of our favorite undergraduate pastimes was to join the assembled freshmen classes in the auditorium where the departmental final examinations in history were to be administered. In the quarter-hour or so before the exams were handed out, Bellairs and I would seat ourselves two or three rows apart, disguised as fellow examinees, and panic the multitude by calling out to each other such gems as, “Don’t forget the dates of Columbus’s last voyage — that’s always on the test.” Or “Remember Henry the Eighth’s wives — you know how the fourth one died?” Or “You know which Asian country was exempt from the Black Death, don’t you?”

Our friendship continued after graduation, in letters and his visits to my wife and me when I was a rising young insurance executive in Chicago and Bellairs was pursuing his graduate studies in English at the University of Chicago. As always, he loved to tell funny stories, not excluding those with himself as the butt of the joke. At his first job interview, to teach English in a Catholic college for women — the venue in which his first published book, St. Fidgeta & Other Parodies, gestated — the headmistress quoted an annual salary to which he politely replied, “Oh, Sister, that would be too generous,” never dreaming that the nun, nobody’s fool in matters fiduciary, would immediately counter with a substantially lower figure.

Writing primarily for the young, Bellairs did publish one adult novel, The Face in the Frost, a masterpiece of sheer terror. Of the works still incomplete at the time of his too-early death of cardiovascular disease at age 53, a number were completed by author Brad Strickland, who has also gone on to write additional originals continuing the fictional existence and adventures of several of Bellairs’ characters.

As you might expect of a celebrated, award-winning and best-selling author, with works adapted for television and translated into many languages, Bellairs is all over the Internet, including reminiscences from his many friends and colleagues. His was a personality best described as droll, an epithet not easily earned or bestowed, requiring as it does a consistent, simultaneous and generous admixture of unique wit and profound wisdom.

To John Bellairs’ inspiration I owe an ever-growing love of literature, of history, of wit, of matchless conversation, and — I cannot deny it — of amusement at the expense of our neighbors.

Patrick Dunne lives and writes in Houston, Texas. After a career teaching literature and writing, he entered law school at age 53 and practiced immigration law until his retirement in 1999. He and Bellairs lost touch in their middle years.