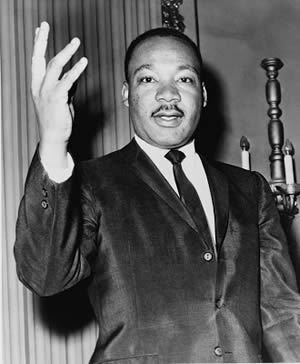

A few months ago, I was driving from Toledo, Ohio, back home to the suburbs of Chicago. Before I left, I had found a CD box set of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches in the back corner of a used record shop and thought they would make for a good companion on my five-hour journey. I started listening to the different speeches and sermons and was in awe of the brilliance of this great man. From the beginning, he had a vision and a rhetoric that inspired hope and dedication for millions of people and future generations. I was so moved that about halfway through the drive I had to pull over because I was weeping.

I was weeping in part because I was inspired and touched by his words but also because I was heartbroken — there was so much more I wished he could have said.

The mix of inspiration and sorrow set in the most when I was listening to King’s most famous address, the “I Have A Dream” speech. King eloquently reminds us of America’s founding promises and how they were remorselessly withheld from African Americans over the course of this country’s history. He advised us to consider the “fierce urgency of now.”

One of my favorite points in that speech is when he explains that black people in America were given a “bad check” from the “bank of justice,” but he refuses to believe it is bankrupt. What King did not mention is what happens when someone else’s account has not only taken all your funds but is also accruing all of the interest. King declaring that it was time for black America’s check to be written was a powerful concept, but I do not believe the check he requested was written for enough.

The check King described asks white America to grant the funds of justice and prosperity that were being taken from black people so we could be equal under the law . . . but that check did not say anything about the interest that had been swelling inside white America’s bank account. There was no memo about white privilege and America’s enduring racial order.

Let me take a step back to explain. See, from 1619 when the first slaves arrived until 1865 when slavery was officially abolished, the relationship between white and black people was that of master and slave, superior and inferior, owner and property. There was rape, murder, separation of families, just complete dehumanization. That was this land’s reality for 246 years — a duration covering more than half of the time both groups have been here.

To rationalize the blatant injustices committed against blacks, white people used things like science and religion to justify the obvious horrors that accompany slavery. For example, Crania Americana by Samuel Morton in 1839 argued that skull sizes separated the races, making blacks unintelligent and passive, thus fit to be enslaved. In 1851, Dr. Samuel Cartwright used his “science” to explain why all blacks are crazy and dangerous.

Even our beloved President Abraham Lincoln acknowledged his feelings of white supremacy despite arguing against slavery. In an 1858 debate with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln said physical differences between blacks and whites prevent blacks from having complete equality. “There must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race,” he said, adding, “I have never seen to my knowledge a man, woman or child who was in favor of producing a perfect equality . . . between Negroes and white men.”

Lincoln’s words foreshadowed what would continue to happen between the races in America — blacks would be given rights but would never truly be equal because of that interest of privilege and superiority swelling in the bank account of white America. Changed laws may have granted some freedom to black people, but when a hierarchy and way of thinking is a part of the foundation of a culture and you learn it and then teach it to your children and your children’s children, it is hard to let that interest, that power, go.

Over the course of multiple generations, the seeds of difference and hierarchy and privilege were sown deep within the consciousness of a young nation. As the seasons passed, the fibers of injustice would be woven into the old roots and new leaves of each era.

By the time King spoke about his dreams in 1963, many seasons had passed. Slavery had been abolished, but restrictions took new forms from 1865 to ’77 during the Reconstruction Era when laws referred to as “black codes” were instituted to continue control over blacks. Though a few pennies of justice did trickle into the lives of black America, the changing status quo led to violence and terror, the Jim Crow era emerged as a legal form of discrimination and segregation, and society continued to debate the humanity and equality of African Americans. From 1877 onward, the legacy of injustice continued until we hit the freedom and resistance eras of the early 1900s. Several great leaders contributed to the Civil Rights Movement, but for many people the name Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is synonymous with the era. He encouraged us not to wallow in the valley of despair and provided hope that all of God’s children would one day be free. He had a dream.

After hours of listening to many of his passionate sermons I wept, heartbroken because I know that the dreams King is celebrated for have yet to be fulfilled.

I thought of how King’s request for freedom and justice was responded to with a “war on drugs,” criminalizing poor blacks’ drug use more than the same drug use in white communities and leading to an exploding and lopsided prison population of nonviolent or innocent black citizens.

I thought of the widely discussed scientific and political reports that resurrected the pseudoscience of the 1850s to declare that black people fell on the lower end of the intelligence bell curve because of genetic inferiority or that they lacked the family structures and motivation to make it out of poverty.

I thought of King’s dream that black people would no longer be the victims of police brutality, and I wept thinking of Sandra Bland, who went from sitting next to my family at church to being pulled over for failing to signal a lane change, thrown on the ground with a knee shoved in her back and then dying in a jail cell she never deserved to be inside of in the first place.

I thought of King’s dream that his black children would not be judged by the color of their skin, and I wept because of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, gunned down while playing in a park. I thought of the time a decade before Tamir when my mother quickly grabbed a toy gun out of my hands and, with fear buried behind her eyes, told me it was dangerous for me to play with toys like that.

I thought of King’s advice to “go back to the slums and ghettos . . . knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed,” but I wept because of the same families still waiting and hoping in ghettos just like the ones their ancestors were forced into. I wept thinking of how many of them cannot escape poverty in part because most states’ tax structures fund schools out of property taxes and create a clear difference in the schools for the rich and the poor.

I also thought of the many daily interactions and situations, the microaggressions that, alone, would just be a little frustrating but in unity point toward a larger problem. For example, I thought of when my white neighbors let me know that it was surprising to see me attending a prestigious university. How those neighbors could wait in line at our community’s grocery store and find that most all the people on the magazines look like them. How so many white women still clutch their purses a little tighter when I enter an elevator or sit near them in public.

I thought of how many times I heard my white peers discuss how a table full of students of one racial or ethnic minority group is “exclusive” or “self-segregating” without seeing the sea of all-white tables that are also filled with students who simply have similar lives and interests. How my white acquaintances still refer to my hair as “unique” or “exotic” but without acknowledging that it could inhibit my success in a job interview.

I thought of how even my closest white friends tell me I’m too much or too preachy if I express a strong opinion or raise my voice in any way. And the most frustrating part: how it is apparently my responsibility to explain my oppression over and over and over again like every generation has done before me and yet see little change in the actions or attitudes of those around me.

I am grateful for Dr. King and his dreams. I share many of them myself. His hope persists today and is visible in the resilience of the black community, the continued quest for justice, the beauty of the art, technology, music, scholarship and culture we create. I am inspired knowing that it was through hope and the hard work of multiple generations that many a freedom check has been cashed into black America’s bank account . . . but, my friends, there is still the interest. America teaches that racism is overtly expressed hatred or bias but doesn’t discuss how it takes larger structural forms or is a part of subconsciously learned privilege and superiority. Either way, there are still differences in the daily lives of black and white Americans because of their race. King’s dreams have not come true yet.

So yes, after thinking about all of this at once, I was overwhelmed, and I wept for my people as I have done so many times before. But as I wiped my tears away and continued my trip home, I tried to think of a few more dreams we could work on.

I have a dream that one day I can drive my car without fear of being killed for changing lanes or reaching for my wallet. I have a dream that I will not have to fear for my children’s safety if I buy them certain toys.

I have a dream that our government will not jeopardize sacred Native American burial grounds or permit militarized attacks on people who are trying to protect the land and water that has truly always been theirs.

I have a dream that one day clean water in Flint, Michigan, will be an assumption.

I have a dream that my white brothers and sisters will understand how certain daily encounters or lifelong stressors I encounter, which they do not experience because of their race, reinforce our enduring racial hierarchy. I have a dream that they will take me at my word when I discuss the oppression I have faced.

My friends, my dreams may sound vast but my request for all of us is small. I dream that we will not subscribe to the dangerous narrative of racial colorblindness and will instead recognize how our past has shaped our present. I dream that we will examine the ways in which we are ignorant of our own privileges, see how they interact with our daily lives, and adjust our actions accordingly. I want us to be able to confidently say that the United States of America has yet to truly be great but that we as a nation will do the work necessary to take one more step closer to the day when we are great, the day when we follow through on the pledge of liberty and justice for all.

Today we, the burgeoning generation, had no part in the goings on of 1619 or 1865 or 1963 . . . but we are the leaves that grew from those same troubled roots. We can see that those fibers of injustice are still pulsing through the core of our nation, infused into every one of us whether we like it or not. So for good and for bad it is our responsibility to make more informed decisions as we pursue the great potential that we have.

Sisters and brothers, these are the American dreams that I have. I hope you will pursue them with me as we go together into the future.

Thank you.

Michelle Mann is a senior at Notre Dame. This is an edited version of the essay she wrote for a Great Speeches class.