The joys and hopes, the sadness and the anguish of humanity in our time and, especially, that of the poor and all those who suffer, are the joys and hopes, the sadness and the anguish of the disciples of Christ. . . . The Church feels true and intimate solidarity with humankind and all its history.

That is how, in 1965, the Second Vatican Council introduced Gaudium et spes, the new pastoral handbook for the Church in the modern world. It was an attempt to recover the original charisma of the gospel message: good news for the poor and comfort for the afflicted, whoever they might be.

Into this seedbed of practical compassion, the Vicaría de la Solidaridad was born. It was 1976, and Santiago de Chile was three years into the brutal dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. At the request of Cardenal Raúl Silva, Pope Paul VI transformed a makeshift commission of local churchmen and their lay supporters into the most trusted and respected organization in the country.

The flagship cause for the Vicaría was the Families of the Disappeared, locally known as la Agrupación. Those families had nowhere else to turn. Over time, the Vicaría became a top-notch team of lawyers, doctors and social workers in the service of political prisoners, exiles and outcasts. It was the only star of hope in a dark sky for the victims of torture, persecution and extreme poverty of those difficult years.

For some, the disappearance, torture and extrajudicial killing of political opponents might seem like the dusty leftovers from the Cold War; collateral damage from far away; statistics in the crowd of nameless thousands whose lives didn’t matter. Military dictatorship was an epidemic in Latin America during the 1970s and ’80s. Authoritarian regimes, supported by the United States in its bid to control communism in the region, had sprung up in Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Bolivia, Paraguay, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. Foreign soldiers were trained in the brutal techniques of counterinsurgency by their U.S. counterparts. Washington didn’t want another Cuba. Or another Vietnam.

Behind every detainee taken away in the night and never heard from again were families and loved ones. Some were broken. Others stood firm. Most never got the answers they were looking for, and most of the perpetrators were never held accountable.

One of those left in anguish was Inelia Hermosilla, mother of Héctor Garay, who was taken away by the Chilean secret police, known as DINA, on July 8, 1974. I met Inelia in ’79, when I was in Chile as a lay volunteer with the Holy Cross fathers. There were many thousands like her. The church seems to have retired to the sacristy, these days, but the mission of the disciples of Christ is far from over.

They dance alone

Cueca is the national dance in Chile. It’s a couple’s dance, and everyone does it for Independence Day, September 18. Dancing la cueca with an imaginary partner is also a tradition. The Chilean cowboy, whose girlfriend is far away, waves his handkerchief high and low, and stomps his feet hard, as if to attract attention. The moves are lively and flirtatious.

- Chile's Long Darkness

- La Cueca Sola

- The Rest of the Story

For the Families of the Disappeared, la cueca sola became a dance of painful longing, a way to denounce the senseless loss of sons and lovers arrested by secret police in the dark of night. In this touching, symbolic protest, it was the women who danced.

Singer-songwriter Sting was moved. I don’t know if he made a clandestine visit to Chile in the years after the coup, or if, perhaps, he saw the Families’ musical group when they toured Europe. The ladies in the group, truth be told, didn’t sing well enough to be making any world tours, but it was testimonial. Their trips were sponsored by nonprofits and human rights groups.

In any case, Sting got wind of it and wrote a song that became a phenomenon. “They Dance Alone” is a sad melody, almost a dirge. He remembers “this sadness in their eyes.”

When Violeta Morales performed la cueca sola, she always put on a gloomy face. Her brother was one of the disappeared. But hers was an intentional gesture, part of a calculated plan. There was little room for authentic spontaneity in orthodox Marxism, comrade. They even had planned feelings. They were linear and simplistic, for the explicit purpose of conscientization. That was a buzzword, even in Spanish. If you used it properly, you identified yourself with the struggle.

Violeta died fairly young. No one knew from what. Younger than the mothers, Violeta was a clandestine operative in the party to which her brother had belonged. No one ever knew which party that was, either. About 10 leftist parties existed during the Pinochet years, all of them banned and operating underground. All fighting to overthrow the tyrant and usher in the new dawn of socialist liberty and justice for all. Good luck with that.

After the dictatorship was over, Sting came to Chile for a concert at the National Stadium, an Amnesty International event. The ladies from la Agrupación were invited to join him on stage. Sting danced a few steps with Inelia, with the whole world watching. She was the one you would pick out of a crowd. She was charming, and Sting’s little waltz with her got an ovation.

But the truth is, la cueca sola wasn’t meant for a big show at the National Stadium, and it was never meant to be sad. It was a rustic affair, more at home in a barrio churchyard, with all the dust and noise, with the smell of mulled wine and fried empanadas hanging in the air.

When Inelia performed la cueca sola, there was no sadness in her eyes. She smiled and winked as if her boy were there before her. That was the right way to do it. The original cueca sola spoke of hope for a future love. In the Agrupación, the dance spoke of a joy that was no longer there. It revealed the emptiness by means of contrary projection.

It's not as if these women had studied the semiotics of dramatic irony. Their dynamic was born of necessity. During the dictatorship, you couldn’t just climb on stage, grab a microphone and denounce atrocities, but you could dance la cueca. People were clever. They got the message.

Inelia was already elderly then. She was small, gray and a little plump. Even so, her cueca was impressive. She was a country girl from Talca. For her, dance was a way to live with what she called “her problem,” the disappearance of her only boy.

Inelia’s daughters, Mónica and Rosario, didn’t participate in the movement. They had their own children to think about, and they were afraid. But I also think it made them sad. Mónica and Rosario did their best to forget, and Inelia understood. But she was a widow. That meant she really danced alone. Her boy was named Héctor, like his father, but she called him Tito.

Sometimes, the judges and the generals called the mothers crazy old women. In court, they would be asked to prove they had even had a son. They would bring birth certificates, pictures and report cards. The official take on it seemed to be that there was an epidemic of imaginary sons and daughters among elderly women in Chile. A communist plot, perhaps, financed by the KGB. The Pinochet regime attributed everything to communist plots. It seemed to justify the repression.

Then came the scandal remembered as The 119. Tito had been detained from Inelia’s home in July of 1974. He was 18. In July of ’75, the regime published a list of “extremists” it said had fled the country and died in armed confrontations among rival factions in Brazil and Argentina. The headlines read: Exterminated like rats. Héctor Garay Hermosilla, Inelia’s Tito, was number eight on that list. It was a lie, an insult to the intelligence. But people believed it.

Alternative facts, I guess. Following the Nazi propaganda model, Make the lie big, make it simple, keep saying it, and eventually people will believe it. Supporters of the regime wanted to believe it. Many thought of General Pinochet as a living saint.

The persecuted left wrote songs to commemorate their fallen comrades. Some were good, but most were awful. The Chilean Communist Party was Soviet-driven, with a history of leadership in the labor movement dating back to the 1920s and ’30s. By the ’70s, its slogans and pamphlets seemed almost burlesque. The Communists had become the Jehovah’s Witnesses of the Chilean left. But there sure were a lot of them.

Tito had belonged to a different group. Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria. MIR, founded by students in the late 1960s, was independent. Miristas were young, zealous and inspired by the Cuban revolution. There were fewer of them, but all very committed.

That was when she stopped asking nicely. That was when she became desperate. That was when she decided to take it to the streets, no matter what the risks might be.

In la Agrupación, wives and sisters of the disappeared tended to be militants themselves, usually Communist Party or Socialist. This was not the world’s first dictatorship, and they knew what to expect. If a political prisoner was held incommunicado for more than a month, it was assumed he would not resurface.

The mothers were different. Most had no political affiliation at all. Their sons had been miristas. That’s all they knew, and some didn’t even know that. Disappearance had begun with the miristas, and the mothers were unprepared. Their worlds came crashing down, but they held on to the illusion that they would someday see their sons alive. Some families lost daughters, too, but most of the disappeared were male.

As the years wore on, even the mothers faced facts. It was harder to imagine your boy tortured in prison for decades than mercifully shot on the day of his arrest. Their hope was to find the bodies, at least. For closure, a chance to say goodbye.

Doris became Inelia’s best friend. Her son, Miguel Angel, was also on the list of The 119. When neighbors and relatives encouraged her to give up, Doris would say, if you lost a sewing needle in your house, you would search until you found it.

Doris had many other children. After Miguel Angel disappeared, they all went to Sweden, some exiled, others seeking asylum. Even her husband went. By about 1981, she was alone in her home on the north side of Santiago. On the streets, though, Doris was never alone. She and Inelia became inseparable. Doris played tambourine in the group. Inelia sang contralto and danced la cueca sola.

Doris died of a pulmonary embolism in 2005. She never got word of her lost son. Inelia died of a stroke in 2006. To this day, no one knows what happened to Tito or Miguel Angel. Did the wind just blow them away? I think not. But the public outcry has blown away. These women were told, again and again, from every quarter, to just get over it. But they never did.

Her Majesty’s seamstress

Talca, Paris and London: That was an old saying. What you were supposed to understand was that, for fashion and finery, Talca was as good as the very best. Talca was a medium-sized city, about three hours south of Santiago on the fast train. It’s not as if everyone there were rich, but they all knew how to do things with style and grace.

Inelia was from Talca, the youngest girl in a large family. Her mother died when she was small, so she was raised by an older sister. Her father never let her out of the house, not even to go buy the fresh bread for the afternoon tea. Chileans stood out on the South American continent because they drank wine like the French and tea like the English. Back then. It’s different now.

Inelia’s father ran a general store. Inelia stayed home and cultivated the feminine arts. She knew what to do with fine fabric and a sewing machine. And that’s how she became Her Majesty’s seamstress.

Inelia was almost 30 when Héctor Garay came along. That was about 1942. The happy couple lived in nearby Villa Alegre for a while and then moved to Santiago. When Héctor became ill, Inelia went to work at the Hotel Crillón.

The owners of the Hotel Crillón were Swiss. It was one of the three fancy hotels in downtown Santiago. It’s gone now. Inelia mostly cleaned rooms, but her employers knew how to use her talents. When it became known that Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, would be making an official state visit to Chile in 1968, Inelia was put in charge of redecorating. She spent two weeks sitting at her sewing machine in the imperial suite, making curtains, cushions and bedspreads.

No expense was to be spared. The manager provided the finest French cloth. I can imagine Inelia there by herself, singing boleros and baladas from the 1930s. She had a nice voice, and she sang in the romantic style of a bygone era.

Queen Elizabeth II arrived, and the visit went according to protocol. Eduardo Frei, a Christian Democrat, was president then. Her Majesty was still a young woman. She enjoyed the view of the majestic white mountaintops from her hotel window. She was fascinated by the long Pacific coastline that promised a prosperous future to the faraway people known as the English of South America.

Inelia got to keep the scraps of the fine French fabric. Which explains why, in ’86, I had cushions and curtains that looked like they came from Versailles in my fourth-floor walk-up flat in Santiago. I was teaching school, then, and I barely made enough to make ends meet.

When the official visit came to a close, the service personnel at the hotel received a generous tip from the gracious hands of the Queen. They were called to the ballroom. All the men had been taught to bow, and the women to curtsy in the grand way. Sometimes, Inelia used that curtsy when she finished the cueca sola. It went with her special smile, the one reserved for shared secrets, and it was always a crowd-pleaser.

During the Pinochet government, France and England ceased being objects of fascination for Chileans. The general’s men made sure of that. Chilean children began to dream of alien superheroes sworn to truth, justice and the American way. Tea and wine are only for old people now. The new generation drinks Coca-Cola.

When Tito was taken, Inelia still worked at the Hotel Crillón. One day, before there was an Agrupación, before there was a Vicaría, Pinochet went to the hotel for lunch. Inelia was called down to wait on his table. The Swiss might be neutral, but they are not indifferent.

I don’t know how, but Inelia managed to arrange an appointment with his imperial majesty, Don Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, at the Diego Portales building. The presidential palace at La Moneda was still a smoldering ruin. Pinochet ruled from the new bunker of steel and glass.

Why did he give her an appointment? Usually little old ladies loved Pinochet. Perhaps he thought she wanted to get his autograph and thank him for saving her country from young communists with beards and long hair. A little favor for a nice lady who seemed like everyone’s mom would be good for his public image. A photo-op, maybe, that’s what he was thinking.

The appointment was for the following week. In the meantime, he found out who she was. Inelia arrived at 8 in the morning. A secretary told her to wait. She waited, sitting on a hard wooden chair in the foyer until 8 that night. Augusto Pinochet stood her up.

That was when she stopped asking nicely. That was when she became desperate. That was when she decided to take it to the streets, no matter what the risks might be. She had nothing left to lose. That was late in 1974, maybe the first days of ’75. It was early summer, in Santiago.

Unto us a child is born

Inelia was over 40 when Tito came along. She already had two daughters. It was a difficult pregnancy. She spent about half of it in bed with symptoms of imminent miscarriage. She managed to hold on to him the whole nine months. She used to say that she cared for Tito like a holy relic, because she put so much work into having him. Maybe she overprotected him a little. Héctor was happy. Every father wants a boy.

Tito was a surprise. Inelia had already had what Chilean women discreetly referred to as the surgery. The doctor had told her that she shouldn’t be having any more children.

Some weeks later, she started to feel bad. The smell of food made her sick and she began to throw up. In the morning. She didn’t know what to think, so she went back to the doctor. She was already pregnant before the surgery. Twelve days.

All the doctors laughed. They said nothing like that had ever happened before. That was Tito. His appearance was as unexpected as his disappearance.

Sons of rebellion

The judges and the generals would tell the mothers that if they had raised their boys right, they would have never gotten mixed up in revolutionary politics. As if they were dealing with drug sales, gang violence and drive-by shootings.

There was another side to that. A moral imperative to change the things you can in an unjust world. That was what drove revolutionaries. But the victors write the history books. If the United States were still a colony, George Washington would certainly be remembered as a traitor to the crown. Either way, Tito’s abduction was unlawful. Due process be damned.

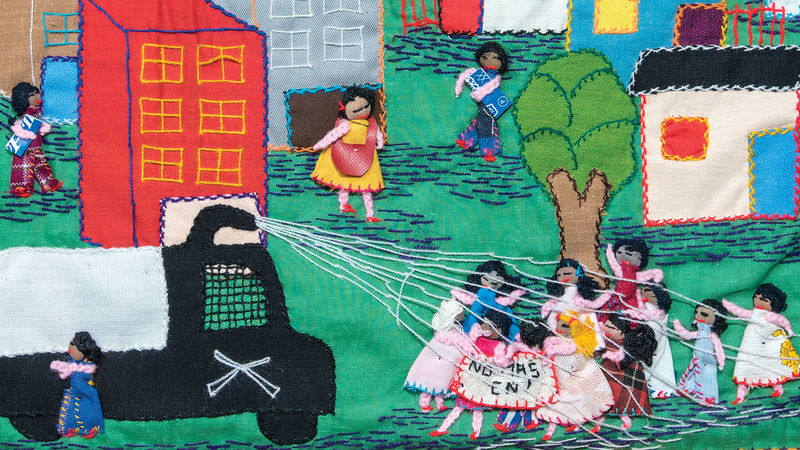

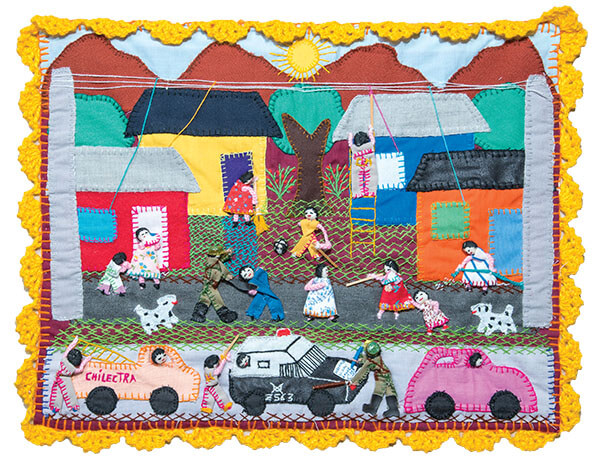

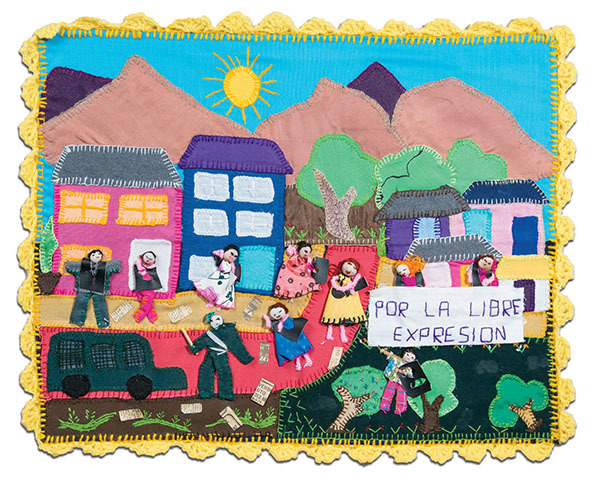

The art pieces for this story are known as arpilleras, created by Chilean women in response to the oppressive regime of the brutal dictator, Pinochet, in the 1970s. These pieces belong to the William Benton Museum of Art at the University of Connecticut.

The art pieces for this story are known as arpilleras, created by Chilean women in response to the oppressive regime of the brutal dictator, Pinochet, in the 1970s. These pieces belong to the William Benton Museum of Art at the University of Connecticut.

Tito went to grammar school in the neighborhood. He played soccer every day at recess. He went to public high school at Liceo 7 de Hombres in Plaza Ñuñoa, about a 15-minute walk from home. He graduated in December of 1973. When he was detained, he was a freshman at the Pedagogical Institute of the Universidad de Chile. That was on Avenida Grecia at the corner of Macul, even closer to home than the Liceo. He wanted to be a teacher.

In the early 1970s, revolution was in the air. The Cubans had succeeded, so others wanted to try. The Pedagogical Institute was locally known as el Piedragógico, the institute for rock-throwing. There were frequent student demonstrations. And plenty of rocks.

Tito was born in 1955. When he was small, there was no TV in Chile. The airwaves became active only in ’62. That was for the World Cup. Even then, only a few people had television sets, so Tito didn’t watch cartoons, westerns or sitcoms. He was brought up on comic books. Inelia bought them for him. His favorite was The Adventures of Tintin.

Tintin was first published in 1930. He was Belgian, and he spoke only French back then. But he learned Spanish in ’58, when Tito was about 3. Tintin was an intrepid teenage reporter with tiny round eyes and balls big enough to get himself mixed up in the most incredible escapades. With his dog, Milou, he lived to challenge the adult world using confidence, stealth and courage.

Inelia actually called her son Tintin for a while. Later, that was shortened to Titín. Most people thought that was just a diminutive for Tito, the common nickname for boys named Héctor, but it had to do with the secret identity of a boy journalist from Belgium.

The Adventures of Tintin was virulently anti-communist and, by today’s standards, even racist. That was not unusual back then. Tintin went to the Land of the Soviets and found everything terrible. He went to the Congo and reported on how Belgian rule there was wonderful. The author went by Hergé, but his real name was Georges Remi. He collaborated with the Germans during the occupation. He worked for a newspaper that fell under Nazi control between 1940 and ’44. That was the golden age for Tintin.

It is perhaps not fair to judge what someone might have had to do, or not do, to survive Nazi rule, but it must be said that Remi’s vision of the world, as expressed in his comic books, fit well with Hitler’s political Darwinism. Remi believed that the empire of superior races was inevitable. When the strong prevailed over the weak, it was taken as a glorious reminder of evolutionary progress.

What did Tintin see through those tiny round eyes of his? If Tito admired him so, why didn’t he become a militant of the extreme right? They had those, too. They were supported by the CIA, and none of them disappeared.

I guess you don’t have to be a genius to get it. Children don’t see the world in ideological concepts. What a boy-child would have emulated in his hero was the intrepid spirit of adventure and courage.

When he decided his life would make a difference, Inelia’s Tintin miscalculated. He applied the surreal omnipotence of the fictitious adolescent reporter from Belgium to the Latin American class struggle, the proletarian revolution, the dream of a new Chile where every child had enough to eat. But Remi’s Tintin was from a fantasy universe where incredible things always worked out on the last page. In the real world, there was no last page, and dreams often failed.

And what was the source of the dream? It’s hard to be sure, but the apple never falls far from the tree. Tito’s father was a soft-spoken man with impeccable manners. While a terminal cancer patient, he spent his mornings at the penitentiary, giving haircuts to the young inmates and letting them know there was always hope. Solidarity, bred in the bone.

Add to that a dose of youthful idealism, Ché Guevara in Cuba, and Miguel Enríquez in Chile. Figure in the hope of the Popular Unity years and the violence of the military coup. There you have him, our Tito, quiet, decided, fearless and revolutionary.

There is a classic drawing of Tintin with his dog Milou. They are running. Milou is running ahead, but looking back at his young master, who is caught in a spotlight. There was a song about a revolutionary fugitive. It made the rounds when Tito was about 15. Son of the rebellion, there are 20 men chasing you. Some songs inspire. Run far, for they will take your life. Remi’s Tintin always got away. It was just a comic book.

The revolution was exhilarating. Danger was like a drug. Once you got started, you couldn’t get enough. It also had a romantic allure. Imagine what it would do to your prestige in high school if everyone knew you were a bona fide member of the most committed revolutionary group in the country. And after the coup in 1973, you became a genuine outlaw, overnight.

There was a lot of adrenaline in that. If you had a can of spray paint in your backpack, it was contraband. Especially if it was red. You take it out, paint ¡Viva la revolución! on a bare wall, and you feel the rush, a fire in your heart. Danger makes you invincible. It’s addictive, comrade.

Tito’s gym bag

Tito’s story eventually came to an end, though it was never resolved. Those who know what really happened to him have never had the courage to speak up. Mónica and Rosario imagine their brother must be in heaven, reunited with his mother and father. The strife is over; the battle done. But Uncle Karl says there is no mansion in the sky. He says that is an alienating fantasy, comrade, intended to make you give up the fight.

Nobody really wants to fight anymore, though. The glorious huddled masses, once poised for victory, have grown tired. There was a slogan: The people, united, will never be defeated. But the opposite seems also to be true: The people, defeated, will never be united. That’s what 17 years of dictatorship have left us. The people traded the lives of the disappeared for the illusion of someday winning the lottery and becoming billionaires. That’s not a Chilean dream, though. It’s an American dream. A North American dream.

The memory of what really happened long ago gets fuzzier with every passing day, like an old photograph worn by dampness and time. Meaning adapts to convenience. Facts can be changed to accommodate ideological shifts. But perceptions always obey the heart. That is, for those who still have one. Dictatorship can leave you without. Or leave yours broken beyond repair. There is no surgery, no medicine, for that.

María Luisa, at the Vicaría, encouraged Inelia to describe her son. I don’t know if it was for the historical record or if it was part of the collective therapy. Inelia would say, He was a rowdy boy. Remembering made her cry. He would come home from school and all the pages of his notebooks would be wadded up like a cabbage.

That was a mother’s perception. All 15-year-old boys seem rowdy to their moms. Compared with the other boys, though, Tito was calm. His classmates were the ones who wadded up the pages of his notebooks. It was a tradition. It meant they liked him. He had friends.

He drew very well, she would say. He would sketch a world where everything worked out, where Tintin and his dog could solve any problem with ingenuity and good luck.

He was a very responsible boy. Too responsible, I think. He took responsibility for the days to come, for the red dawn, for the dream of a new humanity, a world where there was enough to eat for everyone. Where there were schools and jobs and health care for all.

Inelia used Tito’s drawings for inspiration when she started doing arpilleras. That was a local genre, pictures stitched into burlap with yarn and old rags. Embroidery was a fine art, done on linen by society ladies. Arpillera was thicker and heavier, done by simple country women.

Renowned Chilean folksinger Violeta Parra made arpilleras. She was invited to show them at the Louvre in 1964. The rustic simplicity of faraway places fascinates refined citizens of cultured intellectual worlds. They imagine they can magically connect with some exotic universe that Paris and New York have never known. Arpilleras from Chile and wooden masks from Africa.

La Agrupación had the idea of representing the disappearances in arpillera. At the Vicaría, other groups followed suit. The unemployed, the blacklisted, the political prisoners and the families of exiles all got a piece of the action. The plan was to export them to raise money to support the soup kitchens. And to raise awareness. It was all the rage, for a while.

There was even a stage play about the arpilleristas. Tres Marías y una Rosa. Poor women always had names like María and Rosa. It was a collective creation, comrade. That was stylish, back then, as if it were somehow anti-authoritarian, part theatre and part ethnography. As if it obeyed the zeitgeist and not the author. But the author was David Benavente. He was famous enough. And the director was Raúl Osorio. The debut was in 1979. It was a big deal because the regime tried to censor it, but the Ministry of Defense, where Benavente was called to testify, couldn’t find anything subversive about it. Four women stitching pictures. What?

Imagine that, comrade. The Ministry of Defense in charge of theater. The threat of censorship turned out to be a huge windfall for Tres Marías y una Rosa. It leapt to international fame and everyone went to see it. Everyone who had the 50 dollars, of course. That’s what it cost to get in. That was two weeks’ wages, in Chile. But it went on tour to Europe and the U.S., and the price of arpilleras skyrocketed. All social thinkers of any status in the First World had to have one.

Inelia was already a fine arpillerista, even before Tito disappeared. Then she stitched the story of his arrest a dozen times. Every time, she wept, impregnating the burlap fibers forever with her tears. Her arpilleras were among the most sought after, not only for the quality of her artistry but also because she had been an eyewitness. Hers was a first-person account.

An arpillera was not a legal document, but it had a depth of truth you will find nowhere else, comrade. The official account was another issue. It was not always accurate, but the cardinal’s lawyers and social workers at the Vicaría did their best with the facts they had.

There is an official document saying that, at the Metropolitan Cathedral in Santiago, for the Te Deum Mass in 1978, when the cardinal was about to give communion to Pinochet, someone cried out, No, he has blood on his hands! That’s not true. It was Inelia. She just cried, loud and long: NOOOOO!

It is true that Inelia hid out in the Vicaría after that. She had planned it. There was a lateral door on the south side of the Cathedral. The old wooden stairs just outside that door led up to the offices of the Vicaría. She yelled, No, slipped through the door and pressed it shut. It couldn’t be opened from the Cathedral side without a key. Three days later, Inelia slipped out of the Vicaría by way of the Teatinos Street exit. I don’t know if the DINA was unaware of the existence of that exit or if they just decided not to arrest another old lady. Or, better said, the same old lady, again.

In December of 1975, when Inelia stood up on a bench in Paseo Ahumada to ask Pinochet for a Christmas present, she didn’t get away. Back then, the general still dared to walk in a crowd, among the privileged few who had any money for shopping. He did not recognize Inelia, so he stopped and, with all his military gallantry, replied, And what would that be, my good lady? She had him. Give back the son that you stole from me, you old fool.

Desgraciado, I think, was the term she used. She was quickly cuffed and loaded onto a police van. At the Vicaría, she had been taught to call out her name and contact information. Some bystanders walked to the Hotel Crillón and told Inelia’s boss she had been taken.

It’s shocking to see a little old lady in handcuffs. They held her in the old Teatro San Martín, used by the Ministry of Defense as a jail. She stayed there for the rest of the day, calling out her son’s name, Tito, Tito!, so in case he was being held there he would hear her and know she hadn’t given up on him. The guards thought she was crazy. By the end of the day, her boss from the Hotel Crillón had paid her bail and she was set free. He was a good boss.

The guards were right, by the way. Inelia was a little crazy. After Tito’s arrest, her daughters considered taking her to the psychiatric hospital. She didn’t eat or sleep. Inelia used to say, only half in jest, They wanted to cart me off to the looney bin.

Norma Rojas, a social worker at the Vicaría, convinced Inelia it was a bad time to go mad. She had to look for her son with everything she had. Norma’s husband was among the disappeared. She understood the problem and convinced Inelia that this was a mission.

The new Inelia, the one I knew, was the handiwork of Norma Rojas. Inelia Hermosilla became the prototype for the warrior mothers of the Agrupación. She was the pattern that gave shape to what the mother of a disappeared boy should be. Decisive but sweet; authentic but joyful; a fighter but not bitter; committed but not ideological. Madre de detenido-desaparecido had to be a woman with nothing to fear because she had nothing to lose.

Inelia’s madness never went away completely. Norma helped her to channel it for the long haul. The price she paid was having to accept that she would probably never see her boy again. It meant accepting her new identity as a definitive one.

In the beginning, she most certainly did not. Everywhere she went, she carried Tito’s bag with her, the one he always used when he had gym class at school. In it, she put Tito’s comb, his toothbrush, his deodorant, a bar of soap, a towel and a change of clothes. In case she found him, she said. She had it with her that night outside Londres 38, a DINA detention center downtown.

She had heard he might be there, so she camped out for a week by the door. She made friends with the ladies of the night who worked that block. They wrote down Tito’s name, they got his description and they promised to try to extract some information from their clients, the DINA men who worked inside. But they turned up nothing.

Doris spent that week there, too. One night, Inelia thought she saw Tito’s eyes in the back of a truck as it pulled out of the gate. She jumped into a taxi to follow the truck, but the soldiers stopped the taxi. There is no way of knowing if they stopped the taxi because Tito was in the truck, or if they stopped the taxi because he wasn’t in the truck. The whole thing might have been a mother’s wishful thinking. But it might have been a mother’s intuition.

It is possible that was the last time she saw him. She says it was. Even so, it’s hard to know if Tito saw her. For the last time. Doris was there with Inelia, that night.

For the first few months after Tito’s arrest, Inelia would walk out to Avenida Grecia, every night. It was a block from her building. She would wait there, in case Tito showed up, in case they dumped him out, dizzy and confused, unable to find his way home. She would stand under a street light so that, if he appeared, he would see her. She always stayed past curfew. Soldiers would occupy the streets, as they did every night, and she would stand fast.

They could have shot her, of course. But most of them were just teenagers, caught up in a struggle that was not their own. Inelia was, to them, la loca de Avenida Grecia. They would take her by the arm and walk her home. The next night, it would be the same story.

There was an amnesty in November of 1976. That’s what they called it, anyway. They let go of a couple hundred political prisoners who were not real militants. They didn’t know what else to do with them. A condition for the DINA letting go of anyone was that they had never seen anyone or been anywhere they would later be able to identify. That meant that no one who had ever been tortured would ever be set free. The amnesty of those few signaled the definitive disappearance of all the rest.

It happened at the Tres Alamos prison, at the intersection of Departamental and Vicuña Mackenna. An official had told Inelia she might find her son there that day. His name was on a list. Maybe the official looked on the wrong list. But there was a list, and it was proof that Tito had been there at some point.

It was the last time she went out with Tito’s gym bag. The prisoners were released into an interior courtyard of the prison. Tito was not among them. It was a hot morning in late spring, and Inelia passed out. The guards carried her to the prison infirmary. She came to, and the paramedics offered her water, but she wouldn’t accept it. She was afraid of being poisoned. She went home. She had lost her last hope of ever finding her son alive.

It had been more than two years, but starting that day, Inelia went to all the meetings at the Vicaría. She carried her picture of Tito inscribed with the slogan: Where are they? She participated in all the marches and hunger strikes. But the urgency was gone, and with it, the maternal illusion that today could be the day. Anxiety had given way to true courage.

Inelia no longer waited under the street light at midnight on Avenida Grecia. She cleaned out Tito’s room and gave his winter coat away to another boy who was cold. She made arpilleras and she danced the cueca sola like no one else. Until her death in August of 2006.

Nathan Stone spent the last 35 years in Latin America. He was a lay volunteer and, later, a Jesuit missionary in Santiago, Chile; Montevideo, Uruguay; and Manaus, Brazil. At home now in his native Austin, he is doing doctoral studies in history at the University of Texas while caring for his aging mother.