As a nurse wheeled my gurney into the glaring light of the operating room, it dawned on me that I might be gathering the last memories of my mortal life.

Intellectually, I knew that kidney transplants had been around for more than 50 years and that surgeons had achieved a remarkably high success rate, particularly for those patients who, like me, were fortunate enough to find a live donor. On paper, at least, this operation should work.

Still, I had dutifully filled out a living will and assigned my wife, Suzanne, a medical, durable power of attorney. After months of positive thinking, I was, finally, apprehensive.

Then I thought about the man who had been wheeled in minutes before me — the metaphoric angel on my shoulder. A certain serenity enveloped me as I drifted off to the IV drip . . .

The operating table lay at the end of a long journey. A routine physical exam five years ago had discovered blood in my urine. Antibiotics reduced but never resolved the problem until 2006, when the creatinine factor in my urine started to go up. After a couple kidney biopsies, the diagnosis was “IGA nephropathy,” an insidious immune-system-generated disease that had probably been surreptitiously attacking my kidneys for many years.

When the filtering function of the kidneys quits working, there comes the ominous sounding “end stage renal failure.” There is no known treatment.

Worse still, it wasn’t just a mysterious disease on some chart. I felt as if I had a low-to-high-grade flu much of the time, with bonus symptoms of unproductive urination, headaches, malaise, vomiting, severe leg cramps, fatigue and inability to concentrate. These are not exactly the best conditions for anyone, much less a busy judge of the State District Court of Colorado, my job since an appointment in 2002.

A lifetime of dialysis — three- to four-hour sessions three days a week — raised the prospect of recurrent line infections and peaks and troughs in overall physical and mental well-being. After studying the options — and undergoing my first treatment, when forgiving imagination met the harsh reality of painful cramping — permanent dialysis became an unthinkable option.

By March 2008, I knew a kidney transplant was my best chance of survival. But I hadn’t a clue about how to find a donor, dead or alive. All those in my desperate situation have seen the future of “rationed” health care: Tens of thousands of people were ahead of me in a five-year-long line of anxious patients waiting for thoughtful organ donors to pass away. In any case, the prognosis is magnitudes better for recipients of live-donor kidneys.

In addition to the practical prospects of success, live donation can forge an emotional bond between the recipient and the donor, a theory I had completely discounted as psychobabble at the outset and eventually came to see the wisdom of. But at that point the question was whether anyone, soulmate or stranger, would save my life. In fact, I’d been quite upset to learn that a good friend’s sister, who did not personally know me, had been summarily rejected as a possible match. However, it turned out that several close friends had already made inquiries, so the transplant center was focusing on testing them.

I’d even registered for a website that, for a hefty administrative fee of about $600, would give recipients lifetime registration on a site serving as kind of a Facebook of organ transplantation. It’s all perfectly legal — whereas sale or even quid pro quo agreements certainly are not — but feels tainted by the disheartening competition of hundreds of poor souls lobbying potential donors as representing the most compelling or sympathetic case, and the race going to the most aggressive pursuer as if vying for a top job or a cheap Manhattan apartment.

I soured on the site upon discovering that the donor side was populated with a discomfiting array of potential donors, ranging from well-meaning Good Samaritans who hadn’t a clue about what they were facing to an all-but-obvious Nigerian scam artist.

Fate forced me to look beyond those closest to me. My wife and children were not blood-type matches, and my parents, each 79, were considered too old. I had no siblings or other relatives. I didn’t feel comfortable about soliciting friends for a donation. I’d come to an impasse.

Fortunately I have a stepmother who doesn’t believe in just letting fate take its course. She wrote to friends on our Christmas list, telling them of my condition and how uncomfortable I was talking about it. If that turned up no matches, she’d planned to contact local media and arrange a public plea for help. But I wasn’t about to trade on my status as a local judge in order to goad someone into donating a kidney; I envisioned headlines when some desperate litigant in a big case offered me his kidney. And I wasn’t keen on a public perception of my being impaired in my duties. But in the days leading up to the transplant, I realized I wasn’t at the peak of my game and was facing a docket with close to 1,000 cases pending.

The clouds lifted when my transplant coordinator — the medical mediator between you and all prospects — told me that two potential donors who knew me well had come forward. One was my Notre Dame roommate from the class of 1979, Chris Nagle.

Brothers at last

In September of 1975 I was the first of my six suitemates to show up for freshman orientation. My parents had driven me out from Omaha, where my father was stationed as the vice commander in chief of the U.S. Strategic Air Command. I was an only child, and our extended family was small. The only other living relatives were elderly cousins living in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, where my folks grew up and met.

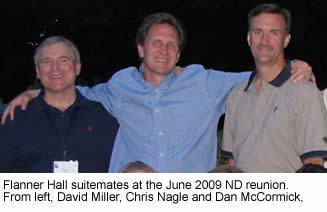

So as I dragged my stuff up to Flanner Hall, Floor 7, Section A, I was looking forward to sharing the experiences of college life with a group of guys who, I was disillusioned to discover, were assigned to room together by how their names fell alphabetically: Don Marcotte of Lewiston, Maine; Dan McCormick of Rockville, Maryland; Gene Meador of Cleveland, Ohio; Chris Nagle of Birmingham, Michigan; and John Naughton, of Marlboro, New Jersey.

Once all of us gathered, I immediately liked them all. As a group, they were smart, athletic and displayed unique senses of humor. Each of them turned into the brothers I never had, the relations marked by constant, unspoken admiration peppered with a form of unending, affectionate ribbing that, for good or ill, I don’t see much in my son’s South Park generation.

Dan and John were engineers, in the stratosphere when it came to math and science. John, the electrical engineer, was particularly finicky about where his stuff was placed in the room or on his desk. Naturally, it soon became obligatory to move his stuff around, sometimes just by a few inches, testing the limits of his situational awareness.

Dan, the aeronautical engineer, wanted to be a United Airlines pilot like his dad. He’d earned his private pilot’s license in high school and would periodically take us for flights in rental planes if we chipped in for the gas. I got a pass on the gas — absurdly it now seems — because I had the only car for beer runs, a beat-up Volkswagen bug, famous for its useless heating unit and great traction on overstuffed excursions in South Bend winters.

A business student, Don was ambitious and tirelessly teased for his Down East manner. A perfectionist, sometimes to the point of distraction, he’d wrap individual donuts in napkins from the dining hall and squirrel them in the lift-up bolsters over our pullout beds. That habit left a not-so-secret stash of donuts for communal distribution throughout the suite, with roommates often meticulously rewrapping donut fragments before returning them neatly to their place.

Gene, my roommate freshman year before we six played musical chairs and settled in, started pre-med and was nobly working his way through school, ending up utterly exhausted after freshman year. The eldest of a large and close family, Gene had the brotherly moxie to break me of my selfish, only-child habits, preparing me for future marrriage, among the most important lessons of my Notre Dame experience.

Then there was Chris, a blond, blue-eyed beach boy with a sincere smile. Amiable to a fault, he had an optimistic insistence on seeing the best in everyone and everything. Seemingly carefree, he was a dead-serious student who was driven less by raw ambition than an internal drive to do well.

His absent-minded-professor routine was one of his only quirks. Chris would constantly forget a book for class, return for his wallet or rustle around for his keys. By senior year, he’d gotten to the point of getting so wrapped up in a story he was telling that he’d wander out in a snowstorm without a coat. He would come flying back in the room, laughing at what a space cadet he was.

The search goes on

In the meantime, it’s not as if everyone else was idle. At a football game reunion last fall, engineer Dan quietly told me that he’d gone through an initial screening but wasn’t a match, so he’d joined my wife on a “four-way” list wherein his kidney would be used for someone who he matched, provided that person could come up with a donor who matched me. In the legal legerdemain of transplant ethics, that sort of trade is okay.

Cleveland native Rod Winn, a buddy from my days in the Air Force Reserves, had also stepped up. Although he’d been a marathon runner and stayed in excellent shape, Rod had a slight heart issue about 10 years ago and, at age 61, was 10 years older than Chris. So Chris was the top candidate: roughly my age, in excellent health and sporting a large enough kidney to match my body.

When I had heard through my stepmother some months prior that Chris and Rod were finalists, I immediately thought of the similarities of these two men. They’d both come from large, very close families, married young and had large families of their own. Both can lift spirits by their mere presence.

More than any other attribute, Chris and Rod are united by strong religious devotion. Chris was devout through school, regularly attending the Flanner Hall Mass. About 15 years ago, he and his wife, Lori, undertook a further personal faith journey from which they emerged even more deeply devoted and convicted followers of Jesus.

Rod is a Mormon and, like many of his faith, has always led a clean life. No drinking or tobacco, and only the healthiest food would enter the temple of his body. Like Chris, he would blush at an off-color joke. Despite dissimilar theological backgrounds, Rod and Chris evidenced authentic Christian witness and cherished their personal relationship with the Lord.

Both Chris and Rod began a battery of medical tests suggesting they were candidates for the next space shuttle. Chris, we then learned, might soon be parting with a kidney.

The setback

Shortly after New Year’s Day, 2009, Chris and I had been approved for the transplant and set a date in early February for the surgery at University of Colorado Hospital in Denver. On top of all he’d already been through, Chris would have to stay in the Denver area, away from the rest of his family and his job, for at least three days before the procedure and seven days post-op. That alone was no small inconvenience, since Chris works as the chief financial officer in his thriving family plastics business connected to the automotive industry.

But by January 9, my condition had deteriorated. I was suffering extreme fatigue and loss of appetite with a heavy pain in my chest. In a week’s time, my progressively deteriorating kidneys had just given out. I was admitted to the hospital for emergency installation of a permanent catheter in my neck to serve as a direct connection to a dialysis machine.

I’m not given to depression, but as they hooked me up to the machine and I watched the blood drain from my body, I found sadness difficult to avoid. At least it worked. As soon as the first four-hour session was over, I had strength I hadn’t felt in several weeks and ate my first meal in a week.

When Chris found out about my setback, his first suggestion was to move up the surgery, which was impossible. Now I had to get healthy enough for the operation.

Chris and Lori arrived by air the Sunday night before the Thursday transplant. It was an emotional meeting, but Chris soon had us all laughing, describing how he and Lori had become lost using the Denver International Airport tram system before my daughter could talk them out of the maze via cell phone. Within minutes, I felt the tension of the previous weeks melt away.

We all camped out in my father’s house in Denver and spent pretty much every waking hour together. It was a great opportunity to discuss everything from the economy to our religious beliefs, our children, our fears and dreams. While the roommates and their wives had regular reunions over the years as a giant garrulous group, this was the first time that Suzanne and I had an opportunity to be alone with Chris and Lori in many years.

A few hours after a preoperative meeting, Chris got a call from the hospital advising him that the chest X-ray showed a spot on his lung; they wanted him to come back the next day for yet another CT scan. True to form, Chris laughed it off by maintaining he was confident that he had “messed up" the scan by holding his breath at the wrong time. But the next day spent awaiting the results was a bit tense. The thought that Chris may have gone through all this only to find that he had a serious illness of his own was a potentially catastrophic irony that remained unspoken between us. It turned out to be a benign cyst, and the transplant was on again.

Reporting at the hospital on February 5, the morning of surgery, we were staged in adjacent gurneys in the pre-op room along with several of our family members. The lighthearted banter of the past days settled into a thin mist over a solemn mood. When the surgeons called for Chris, he asked to be wheeled over to me. We both sat up and embraced, after which we held hands and Chris said a prayer asking for the Lord to be with the surgeons and us.

He prayed with the sincere and meditative tone of a voice of one who regularly speaks to Jesus. I was at once calmed by the words and immediately overcome with a feeling of pure love, which could only have been the movement of the Holy Spirit. I cried as I have never cried in my life. I was at once thankful for the blessing of knowing this special person while at the same time fearing for his safety.

I now understood the meaning of the “emotional bond with the donor” theory I’d earlier scoffed at. Caring about the fate of the donor turns one’s heart outward, away from self-absorption.

Side by side

Five minutes later, they came for me. When I awoke three hours later, Chris and I were again side by side, as we had been three decades ago in a place that suddenly felt present again.

Chris spent three days in the hospital, and I spent four. By the second day, Chris was edging his way into my room with his IV tree and a walker. He happily reported that the pain was not nearly as bad as advertised. He even predicted IV-tree races around the hallways, harkening back a time some 33 ago in which we inadvertently damaged the dorm wall during a shopping cart race at the end of fall semester finals. We laughed, remembering how we’d ended up going home for break late, spending the entire night scouring South Bend for wall plaster so the hole could be fixed and painted before Brother Pete made his rounds the next morning.

Although we never felt up to racing, our sophomoric sense of horseplay recovered swiftly. We became fast favorites of the nursing staff, who affectionately referred to us as “the Notre Dame boys.” Exploiting this goodwill, I tried to convince a young nursing student to sneak into his room while Chris slept and tie his IV tree to his bed, revising an old college gag where one of us would crawl under our back-to-back desks and tie the other’s shoelaces to the post for a delayed pratfall. Wisely, the young lady opted to continue her career in nursing.

During recovery I was gratified to see people who didn’t know Chris treat him with almost reverential respect for the sacrifice he had made — each very likely wondering to themselves if they would have the courage to undergo such an ordeal for someone they called a friend. As they watched Chris laugh away the moment, they were looking in the eyes of a truly selfless hero.

I didn’t want Chris and Lori to leave. The time we had spent talking, crying, laughing and praying together were among the most profound moments of my life. But as the car pulled out of the driveway, I knew he’d come back soon. That was more than an instinct: As I turned back to the living room, I noticed Chris had forgotten his favorite shoes sitting in front of the fireplace. God’s in His heaven and all’s right with the world.

Dave Miller and Chris Nagle are doing well in their recovery. This article was written with the assistance of Gregory Solman, Notre Dame class of 1980.