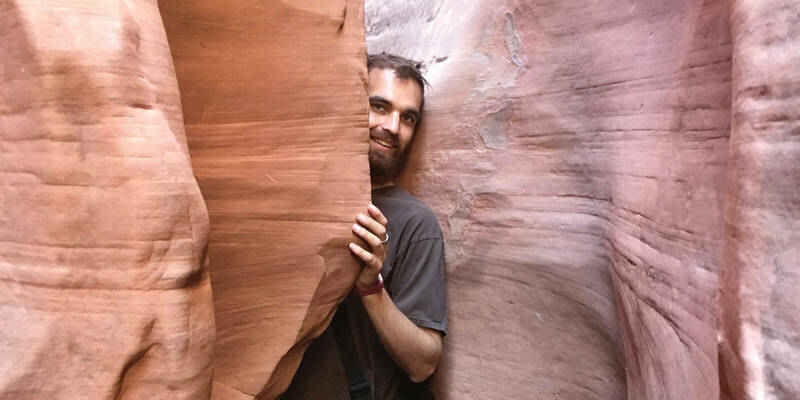

Editor’s Note: On a peaceful Saturday morning in early September I sat in my backyard, savoring the scene before me: the grass and trees and black-eyed Susans, all feeling different now — as the sunlight and scents took on an autumn mood. It reminded me of a memorable essay from years back, and that got me to conjuring a list of all-time personal favorites published in the magazine over the years. I decided to share them with you, a new one each Saturday morning until the calendar reaches 2024. Few stories have affected me as profoundly as young Morgan Bolt's narrative composed as he dealt with his terminal cancer. It came to me as a book-length manuscript and I culled from it the story we published in July 2018. I trust it will move you as it moved me — with its humanity, wisdom, extraordinary faith and barebones honesty. Morgan died five months after this was published. —Kerry Temple ’74

When I threw up two mornings straight I knew something was amiss. Christina, my wife, said I had to call off work and have a doctor look at me. So I went to an urgent care center where a wonderful lifesaving doctor whose name I do not recall spent about three seconds looking me over before telling me I definitely had some “large, very concerning masses” in my abdomen and needed something called a PET scan. As soon as possible. Like, in an hour or two.

He wrote it all down on a sticky note for me and printed off directions to the nearest hospital, which was great because I had no idea where any hospitals were in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, area. I had only lived there while going to college and had just graduated a few months earlier. That doctor was the first in a long procession of people who have saved my life over the past few years. I owe my life to his promptness and willingness to convey the likely severity of my condition. I wish I knew his name.

I drove to the hospital, went in the wrong entrance, and was told by a pair of friendly custodians how to get to the emergency room. There I gave the receptionist the sticky note the doctor had signed to expedite the process, and they took me to a back room right away. I turned on a football game and drank my first liter of contrast, which, as I understand it, is radioactive sugar-water that tastes worse the more you drink of it. I would drink many more liters of the stuff in the coming years, but at the time I did not know that. All I can recall thinking then was that if I had cancer, I’d simply have to beat it. That, and that the Indianapolis Colts’ defense needed some work, having given up 51 points to the Pittsburgh Steelers.

After my first set of PET/CT scans, which involved taking a nap on a surprisingly comfortable plank while slowly being fed through the middle of a giant donut-shaped machine, Christina joined me, having gotten off work once it became clear that something was seriously wrong. As one doctor put it, “If you were old, eh. But you’re young, so we’ll fight this thing with everything we can.” I appreciated that.

I see cancer as a messy, ugly, yet necessary byproduct of the ever-changing planet we inhabit.

The PET/CT scans showed multiple large masses from my pelvis to my diaphragm. I’d experienced morning sickness because, not unlike during a pregnancy, my organs were being pushed around by the thing growing inside my belly — a belly that now seemed larger than normal, which I had attributed to marrying a fantastic cook the previous year.

The rapidly assembling team of doctors assigned to me, some from specialties I hadn’t even heard of before, scheduled a biopsy for the following morning.

It took over a week for the biopsy results to come back, as they had to send my tissue sample out to Mayo Clinic to figure out what was growing inside me. My parents arrived from Corning, New York, and we set to work researching kinds of cancer, types of treatments, and hospitals that deal with rare cancers. Well, my parents and wife did. I recall watching BBC’s Sherlock and eating a ton of candy, since Halloween was just a few days back and everything was on clearance sales.

Then we met with the bariatric surgeon, who said an official diagnosis would take a couple more days but that it looked like something called Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumors (DSRCT), a soft-tissue sarcoma that’s classified as a pediatric cancer. Little information is available on DSRCT and much of it may not be entirely accurate. But a mere 15 percent of people with it are still alive five years after diagnosis, according to Wikipedia, which the surgeon had to turn to since he, like most doctors, had never heard of DSRCT. Only two hospitals in the world really deal with it — at least with any efficacy. We (my parents and wife) did more research on treatments, hospitals and just how serious and life-altering this would be. For my part, I made a lot of progress in Real Racing 3, a car racing game on my phone.

Then the major, ineluctable changes to our lives began. It became clear that my treatment would last at least a year, involving too many procedures to make working feasible. So Christina quit both her jobs and I quit both my part-time jobs as well. We moved into my parents’ basement. Cliché, I know, but they have an in-law suite with a bathroom, kitchen, living room and bedroom, so it’s much better than it sounds. Better yet, I was still young enough to be carried on my father’s insurance.

The next week or so passed in a blur I scarcely remember and don’t particularly care to recall in detail. We decided I should go to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, since they had oncologists familiar with DSRCT, two surgeons willing to operate on people with DSRCT, and a doctor working on an experimental radioimmunotherapy trial.

The first day at Sloan Kettering stands out in my mind more clearly than any other day from that time. We met with enough doctors that I quickly lost track of who specialized in what. My new main oncologist asked if I wanted a rundown of all the types of chemotherapy they had planned — and their side effects — so of course I said yes. After about 20 minutes it all started to sound the same, but I wanted to know what I was facing. Next, I had a slew of scans — a PET, a CT and an MRI. They also did some other scan, the name of which I’ve long forgotten, that mapped how well my kidneys were draining. The first scan showed that one of my kidneys was a little inflamed, and that the associated ureter — the tube that drains your kidneys into your bladder — might be pinched by tumors.

My wife and I drove back home, a little shell shocked as you might imagine, and found ourselves stuck at a toll booth that was charging us $1. Neither of us had any cash. In some ways that was the lowest point of my life, though really it shouldn’t even crack the top 10 with everything I’ve been through. Yet somehow the fact that there had been no toll heading eastbound but there was one returning westward, coupled with the ridiculousness of not having even a single dollar bill between the two of us and the booth’s inability to accept debit or credit cards, made it seem like the end of the world. Coming from our first glimpse at our new life in the pediatric cancer ward didn’t help either, I’m sure.

After trying to explain our situation to a toll road employee who, I thought, said to just drive through and not worry about paying, we went home and got a bill for $1 in the mail a week or two later. We have an E-ZPass transponder now.

A couple days later I had my first surgery, a planned 45 minutes that ended up running into the four-hour neighborhood. They placed my double-lumen Mediport, a device in my chest just under my skin that allows for much easier IV access and infusions of chemotherapy without damaging my skin and veins. They also put stents in both ureters, which apparently was an unexpectedly difficult process thanks to the tumors pinching them, but my superbly talented surgeon got them installed.

Thanks to the stents I didn’t have to have a nephrostomy tube — basically a reroute of my urinary tract from my kidney out through my back into a plastic baggie — like they had said was a possibility, so that was a win. I peed fire for a few days, but that was worth saving my kidneys and the ability to urinate conventionally.

I woke up from that surgery vomiting as I was wheeled out of the operating room, which my anesthesia-addled mind knew was bad but couldn’t figure out why. I woke up again a little later in the recovery room, feeling a trifle less terrible, though I still threw up a couple more times before the anti-nausea meds kicked in. I remember thinking that this wasn’t worth it if it only bought me a few extra weeks, so I needed to keep living a while longer.

A week or so later I started chemo, a reportedly easy, low-dose regimen that was part of an experimental protocol to see whether the combination of drugs was, as my oncologist put it, “tolerable” for people with DSRCT to start before moving on to the more standard-protocol chemo regimens. If I was reading between the lines correctly, that meant people didn’t go downhill any quicker on this experimental regimen than they would have otherwise. Comforting.

On this supposedly easy and tolerable chemo I was violently ill. I got a bacterial infection called clostridium difficile, or C-diff, barely ate and fell to my lowest weight ever, some 60 pounds less than before I started treatment, little of which I needed to lose. Other than several pounds of tumor, of course. Fine. And maybe about 10 pounds or so that I’d gained in college. By any reckoning, though, there’s no way someone with my 6-foot-2-inch frame should weigh in the low 150s. It was the roughest month or two of my life. I was glad to leave it behind me.

As you can see, my cancer has necessitated a lot of treatment and medical attention, none of it particularly pleasant. But I have almost never felt uneasy about it, and never for more than a fleeting moment. I know I can’t speak for anyone else who is taking this journey with me, but I have only rarely felt unsettled about this whole cancer thing. Have I looked forward to the various toxins that are chemotherapy? Hardly. Have I been excited when surgeons describe an upcoming procedure and its recovery process? Not exactly. I’ve been nervous about radiation, my next surgery, impending scans and new regimens of chemotherapy. But am I unsettled? Am I shaken and rattled to my core? Have I fallen apart and questioned the fairness of life? No.

Most of how I’ve remained largely upbeat and unfazed through my grueling treatments is due to my faith and how it compels me to regard the world. I certainly cannot — or at least should not — give myself too much credit for this. By nature I am laid-back and tend, by whatever combination of nature and nurture, not to worry about, well, much at all. I took my diagnosis better than anyone else in my life. Nobody had to worry about keeping me cheerful or relatively happy. Actually, I’ve had to comfort people far more than the other way around.

The most significant source of strength I draw from as I deal with cancer is not my nature or some magical coping mechanism. The most important, most helpful sources of inspiration and strength for me have been my beliefs about God and the way God’s world works.

Like anyone, I have considered some of the most widely asked questions in human history: Why does evil exist? Why do bad things happen to good people? Why do children get cancer? Why does God allow hurricanes, avalanches and falling tree branches to kill people? And I have heard many people describe cancer as evil.

But cancer, in my opinion, is no more evil than weather, or mountains, or trees or any other part of this world that can and does kill people. Cancer is simply a part of life on this good earth. Sure, it causes suffering and death, but so do storms, avalanches and falling tree limbs. As far as I am aware, nobody claims that clouds, snowy peaks or trees are inherently evil. People may hate cancer, but that alone does not make it evil. Cancer may bring only suffering and death, yes. But cell division? That keeps us all alive. It allows us to grow and heal. And what is cancer if not a hurricane of cell division? And cell division is just like any other part of this incredible and dynamic world.

Tucked away in the famous Sermon on the Mount is a clear, concise explanation of how the world works, an explanation that too often remains overlooked. Jesus, imploring his followers to love even their own enemies, says that God “makes the sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous” (Matthew 5:45). He is talking about the need to love everyone, just as God blesses everyone with sunrises and nurturing rains. But this isn’t merely an imperative that we love even those who do not love us. It reveals an important truth about God and the way God made the world.

This world, Jesus says, rains and shines on the righteous and the unrighteous — on the people who love God and on those who don’t. People ranging from good to bad get weather ranging from good to bad more or less equally. God does not discriminate when it comes to who receives what from the natural systems of this world. The natural processes simply function as God created them, and whether or not we like them is basically irrelevant.

I see cancer as a messy, ugly, yet necessary byproduct of the ever-changing planet we inhabit. Our world changes continually, and survival for all living things depends on constant adaptation. It is extremely fortunate that life has the capacity to change. Without that ability, life on this earth would have ceased long ago. That the very blueprints for life — our DNA — can and do change, and rather often, makes me immensely grateful to God for having the audacity to create this universe as it is — a universe of change where the building blocks of matter are made of spinning, moving, dynamic parts. Change and movement permeate God’s creation.

I remain immensely grateful that the world and universe are all the more spectacular for their ability to change and adapt, to exhibit God’s continual creative power and allow us to work as co-creators with God. If cancer, the product of cell-division gone awry, is a necessary result of such a splendid and dynamic world, one we can interact with and enjoy, that is fine with me. Even when my own life is at stake.

I slogged and skipped my way by turns through a few rounds of chemotherapy, at times exhausted to my core by the 14-hour days at the hospital, at others enjoying some of the best sights and activities New York has to offer. Those low-dose drugs were part of an experimental protocol that could also cause abdominal pain so bad I could scarcely move at all, and not without swearing more than seemed appropriate for a pediatric hospital.

Somehow I made it through those first rounds of debilitating chemotherapy. It felt much longer than the month and a half that it was, and I never looked back. I simply gritted my teeth for what came next: the real chemo, the tough chemo, the chemo that would take my hair and send my blood counts plummeting, and maybe, just maybe, have some effect on the tumors inside me.

I can’t remember exactly when I started the tougher chemotherapy cycles, or even the names of the different drugs I received. With the new regimen of chemo came a change in side effects. I didn’t feel quite as violently sick, and I didn’t have any more complications like C-diff messing everything up. I did experience the overall sense of blegh I call “feeling chemo-y.” It’s not terrible, or at least not the worst thing ever, but it is all-encompassing and it does feel undeniably not right. I felt exhausted, and an overarching sensation of something being very amiss, very toxic, very unbalanced sat in my torso.

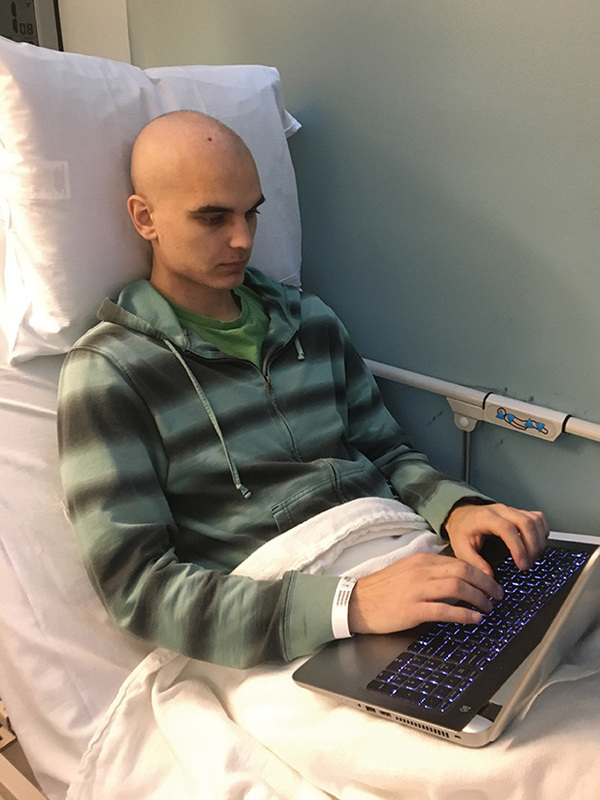

Some days I needed two infusions of a bolus, a giant baggy of IV hydration, before I could start the higher-dose chemo. Some days I came to the hospital by 7 a.m. and didn’t leave until 8 p.m. I napped when I could, finished watching all of Top Gear on Netflix, and got into the habit of writing more, working feverishly to complete my Tamyth trilogy, the young adult fantasy series I began when I was 14 and restarted in college. I managed to finish it before my first major surgery, which was my hope.

I didn’t exactly expect to die in surgery, but I also don’t know that I thought I’d live very long either. I don’t think I was overly morbid about it. The simple fact was that in all likelihood I didn’t have much time, so I decided to be fine with the prospect of dying, even as I hoped I’d live long enough to accomplish some of my goals.

These intense cycles of chemotherapy lasted three weeks. The first week I received infusions of chemo for two or three days, then continued going into the hospital for IV hydration. After that I had two weeks off to recover. I liked those two weeks off. Usually by the second off-week I’d be feeling well enough to do more than sit around all day. We managed to explore more of New York during the recovery weeks. Some of my favorite places include the American Museum of Natural History, the Met, the New York Public Library and Bryant Park, and a secret spot in Central Park.

Usually by the second off-week I’d be feeling well enough to do more than sit around all day. We managed to explore more of New York during the recovery weeks.

This spot is on a pleasant knoll with a view of some stately trees, and it’s one of my favorite places to sit and read. I once saw a man walking his pet tortoise there, which provides a good indication of its tranquility. A bathroom is really close by, so that’s handy too. That’s as much as I can tell you while keeping it a secret.

On the whole, the higher-dose chemotherapy went well. It also reinforced a mantra my doctors repeated again and again: Chemo affects everyone differently. If I was throwing up most days on the easy stuff, surely I’d be sick constantly on the harder drugs. But that proved wrong. Overall it progressed pretty smoothly.

“Overall” being the key word. I made a couple late-night trips to the inpatient center, sometimes staying a week or more until my blood counts rose sufficiently. As my blood counts dropped with each cycle, I grew increasingly light-headed and fatigued, and a few times needed transfusions. If you donate blood regularly or even occasionally, thank you.

Sometimes my platelets were low, but my hemoglobin levels, among others, were doing well enough that I only needed platelet transfusions. Those were fun because, as we discovered one night around 2 a.m., I’m allergic to platelet transfusions — most likely because of the preservatives that keep platelet samples stable and viable before they’re infused.

My blood counts also affected what I was and was not supposed to eat. Since my blood counts started dropping and my immune system grew suppressed, I was forced to follow a low-microbial diet, which meant I couldn’t eat any fresh fruits or vegetables. Hiccups also made these rounds of chemo interesting. These weren’t your average hiccups. They were, if I may say so myself, impressively loud. And very annoying. I got a pill that usually made them go away pretty quickly. The hiccups certainly weren’t the worst side-effect of those treatments, but they remain one of the weirdest.

Then came my tumor resection surgery. Scheduled to last somewhere between 6 and 14 hours, it would mark the beginning of the cancer’s removal. Chemotherapy might slow the growth of my tumors, or perhaps even keep the disease stable, but it was never expected to shrink my tumors, much less get rid of them entirely. Only surgery could get rid of them.

So I drank two liters of ginger ale with a whole bottle of Miralax the night before to clear me out in preparation for spending a day under anesthesia. Given my previous difficulty with nausea under anesthesia, I got a scopolamine patch before I went to the operating room and had Zofran infused while I was under. I woke up about 7 or 8 hours later in the recovery room, feeling all right, thanks to my epidural. My only real complaint was the nasogastric (NG) tube which ran down my nose and throat to vacuum out my stomach, which remained necessary for several days as it took a while for my insides to wake up and start running in the proper direction again. The NG tube remains my least favorite part of major surgeries since it dries out my throat terribly.

My second least-favorite part of recovery is the Foley catheter. Foley catheters are nice in a way, since the last thing I want to do when I have a fresh incision from my sternum to my pelvis is get up and walk every time I need to pee, but mostly they’re annoying, uncomfortable and stupid.

I’d still take surgery over chemo any day. Surgery makes the most sense to me out of all the treatments I’ve had. With surgery, I wake up and see what I need to deal with, and make myself get up and walk and recover as quickly as I can. It leaves visible, easily understandable wounds that heal quickly, in my experience. Chemo just makes you feel terrible and has no visible physical effects — other than hair loss and weak, thin lines in my fingernails. But with surgery it’s easy to see what hurts and what needs to heal, and how quickly I recover from surgery falls to an extent under my control.

During my first night in the recovery room I didn’t sleep much. I asked for ice chips and water far more often than they were able to give them, and I listened to the staff talk at 4 a.m. about Game of Thrones and Scandal. I also smelled the smoke from an apartment fire, which was disconcerting. Recoveries typically started with a day in which I felt I’d never recover, or at least couldn’t imagine recovering, since I felt so beat up. But the next few days would consist of making myself sit up, get out of bed, walk slowly along the hospital hallway, and eat Jell-O. This time I pushed myself pretty hard and walked more laps of the hallway until six days later they cleared me to walk myself out of the hospital and go back to the Ronald McDonald House.

To be honest, I’m a bit inclined to brag about how quickly I recovered from surgery, and I like to think it’s because I’m super cool or tough, but really I just got lucky and was blessed to have everything go well. It wasn’t through anything special about me or anything I did. And that’s an important point: People receiving cancer treatment aren’t warriors or fighters. Indeed, cancer isn’t a battle at all.

I know that contradicts the way our culture views cancer but, in my experience, this is true. Cancer isn’t a fight, and we patients aren’t necessarily brave, either. I know the nearly unanimous response when someone is diagnosed with cancer is to call the person “brave” or “courageous,” assuring ourselves that our loved one is a fighter who can beat their new affliction. But it doesn’t matter how strong or courageous someone is. That won’t cure their cancer. Only treatments like chemotherapy, surgery and radiation can get rid of someone’s cancer. Being brave, stoic or tough helps people deal with such treatments, sure. But it isn’t a viable treatment itself. It isn’t a guarantee that they’ll ever get cancer-free. I know over a dozen people who would still be alive today if it were.

I get that cancer is scary and people like to feel as if there’s something they can do about it. We don’t like things that are beyond our control. It makes us feel better to think that as long as we’re brave enough and determined to really fight, we’ll be OK. But cancer doesn’t know or care. Cancer just is. Cancer is a disease, not a battle, and we need to be realistic about that.

I don’t consider myself brave for getting through more than three years of cancer treatment. I just haven’t died yet. That’s it. It’s also worth noting that not everyone who gets cancer feels like they can fight it, or even wants to fight it. Telling someone they’re tough and brave and can beat it when they don’t feel that way isn’t often very helpful. Besides, bravery doesn’t always mean a willingness to fight. In a lot of ways, it’s braver to accept our own mortality than it is to do whatever it takes to stay alive simply because we’re afraid of death.

On the whole, I felt significantly better after my surgery. Physically, I was relieved of seven or eight pounds of useless blobs taking up space in my abdomen — along with my appendix, spleen and something called an omentum that I’d never heard of before and apparently don’t need. I also had an awesome new foot-long scar running down my stomach, and I now felt like I could handle any surgery or other treatment they might throw my way. My confidence that things would work out rose, even as I tempered my expectations with reality, with daily reminders that my life expectancy was not long and that, in fact, I’d already outlived it.

I remember the exact moment in March 2015 when it hit me that, had I been born even 30 years earlier and only had access to the care available at the time, I would be dead already. Christina and I were walking back from Central Park and had only a few blocks to go to reach the Ronald McDonald House. And somehow I was imagining living in medieval Europe (as one does) and it occurred to me that applying leeches might have been the best that anyone then could have done for me. My thoughts turned to the many advances in medical care over the years. Especially at Sloan Kettering, innovative treatments continually emerge. I’m alive today because of the latest and best medical care in the world.

That level of medical attention has allowed me to pass milestones in my life that I never expected to reach once I started life as a cancer patient. I lived to celebrate my second wedding anniversary, then my third, then my fourth, then my fifth. My past three birthdays also snuck up on me. Every year I’m pleasantly surprised when my birthday rolls around, even as I don’t seriously expect to reach the next one.

Some people dread birthdays and getting older. Maybe because I’m only 26, it is easy for me to call that foolish, but I get upset when people complain about another year of life they’ve enjoyed. I will always be happy, not heartbroken, if I reach my 40th birthday — or even my next one.

I should be filled with gratitude every moment that I live. I cannot go long without something imploring me to be more thankful, to take a step back and not take life — and the quality of life that I enjoy — for granted. Partly that’s due to my nearly constant promptings to be thankful. Whole days pass when my discomfort or nausea is merely an annoyance and the sight of my scars makes me think only of how badass I am now. If you saw my scars you would agree. They’re pretty legit.

But still, hours go by when I forget to appreciate even the most basic blessings, like the fact that I haven’t died yet.

Every six to eight weeks during the maintenance chemotherapy that followed, I would have another set of scans. My scans continued to show some spots of suspicion and interest. Some came and went, and some stayed steady or grew slowly worse. By early 2017, my incredible surgeon proposed a couple surgeries to remove everything that was lighting up suspiciously — four spots in my chest and three in my abdomen.

First I had another laparoscopic chest surgery to remove everything that looked suspicious. It went fine and they removed several spots, about half of which tested positive for DSRCT, the rest being nothing more than lymph nodes.

A couple weeks after that chest surgery I had yet another abdominal surgery, the fourth time my largest incision scar has been opened up (so far). Three spots were removed, two of which were cancerous. They tried a new radiation technique, in which a radioactive fluid drips onto the spot where the cancerous nodes were removed for half an hour before I got closed up. I’m not a big fan of receiving radiation on my belly, but this seemed like a neat way to send some targeted radiation to a potential problem area. After all, although the goal of surgery is to get every bit of cancer out, there’s always a chance even one cell might be left behind. And one cell is all it takes.

For now, my cancer treatment involves a lot of waiting for results that are not likely. The best case scenario is a prognosis of No Evidence of Disease, or NED. NED is the closest I will ever come to “cured” or “in remission.” They just don’t use that kind of terminology with cancers like DSRCT. The best we can hope for is to find no evidence of cancer actively growing in me. It’s like space aliens. Seeing them would prove they exist, but not seeing them will never disprove their existence. NED just means we don’t see any cancer, and I may never get there.

I continue to try different mixes of chemo and clinical trials, keeping maintenance chemo in my back pocket. For now, my future is determined scan by scan. Christina and I await scan results we don’t ever really expect to get, scarcely daring to hope for the good news we desperately desire.

A lot of times it feels like I’ve done more waiting than anything else the past few years. I’ve waited for my initial biopsy results, waited for bloodwork, waited for my urine to get to the right specific gravity to start chemo, waited for chemo to end, waited for radiation, waited for a clinical trial, waited for surgery again and again and again, waited for relief from shingles, waited for painkillers to kick in, waited for constipation and diarrhea to end, waited for hemorrhoids to heal, waited for clinical trial results, waited for scans to start, waited for scan results. I’m waiting right now to see whether I’ll qualify for a clinical trial. I’ve been waiting since I finished my planned course of treatment over two years ago for the results we want, for the seemingly unachievable NED pronouncement. In a lot of ways it feels like a morbid version of Advent.

Advent, after all, is about waiting for the arrival of the Messiah, the deliverer who will establish God’s kingdom here on Earth. Advent might mean “coming” but for me it has always felt more like “waiting,” waiting for an arrival certainly, but waiting nonetheless. For me, the best part of the Advent season is the knowledge that, though we wait for Christmas Day to celebrate the birth of Jesus, Christ has already come. God is already here with us. God’s kingdom is already among us, existing everywhere we work to spread God’s love.

I continue to try different mixes of chemo and clinical trials, keeping maintenance chemo in my back pocket. For now, my future is determined scan by scan.

I may never get the good news of NED, but I’ve already received far better news that makes that all right. I might wait the rest of my life for clear scan results that never come, but at least God is with me through it all.

That leads me to another thought, another way my cancer has changed the way I understand how God relates to the world. When we got the diagnosis, I took the news much better than a lot of other people. Better than anyone, honestly. While some of this is due to my generally carefree nature, I also attribute a good part of this to the fact that I, not someone I love, would have to go through this hellacious process.

It would be far worse for me to have to watch someone I care about enduring round after round of chemo, surgery followed by surgery, followed by debilitating radiation treatment, followed by more of the same. Several people have said that they wish it was them, not me, going through it all. It is, I think, a natural reaction when we see people we care about suffering. We want to take it from them, to carry their burden and give them some respite from their trials. Which is why I would never let someone take my cancer from me and bear it themselves, even if that were possible.

The mental anguish that others must deal with is not something I would care to endure. I sincerely doubt I would have remained half so calm and happy were it my wife, not me, going through all these miserable treatments. It’s so much harder to see a loved one endure something difficult than it is to go through it yourself.

I think that’s how God feels. Maybe it was so unbearable to see people muddling through their own mistakes that God came down to go through it all for us, providing us with clearer guidance and giving us a way to be free from our wrongdoings and the suffering they can bring. While it’s impossible, of course, for any of us to actually take someone else’s disease and go through their misery for them, it’s comforting to have a God who can do much the same thing. And who, in fact, already did.

Morgan Bolt, the son of Marvin Bolt ’92M.A., ’93M.A., ’98Ph.D., was diagnosed with cancer in October 2014, with little expectation that he would survive for another year. This narrative was drawn from Cancer Is Not Evil, a book-length manuscript that he hopes to publish, tracing his life’s events and thoughts over the past four years.