Throughout nearly four decades of his 55-year career in journalism, Red Smith ’27 piled up recognition like cordwood. A 1958 Newsweek cover story called him “Star of the Press Box,” and a 1981 60 Minutes profile on CBS went further: "America’s foremost newspaperman.” The Pulitzer Prize he won for commentary in 1976 noted, “In an area heavy with tradition and routine, Mr. Smith is unique in the erudition, the literary quality, the vitality and freshness of viewpoint he brings to his work and in the sustained quality of his columns.”

Acclaim didn’t end with his death in 1982. At the close of the 20th century, Editor & Publisher’s list of the 25 most influential newspaper professionals of the past 100 years included Smith — along with H.L. Mencken and Walter Lippmann. He was the only sportswriter on the honor roll. And besides his nine book-length collections, Smith’s writing still finds its way into anthologies and others’ volumes. In The Best American Sports Writing of the Century (1999), editor David Halberstam selected five Smith columns, the most of any contributor, commenting that he “was far and away the best sports columnist of his time, and he stayed at the top of his game for more than 30 years: his columns at their best were like miniature short stories.”

Born Walter Wellesley Smith on September 25, 1905, he didn’t adopt the byline “Red Smith” until 1936, when he started writing sports for The Philadelphia Record after stints at the Milwaukee Sentinel and the St. Louis Star following graduation from Notre Dame in 1927.

“I never had any soaring ambition to be a sportswriter, per se,” Smith once said. “I wanted to be a newspaperman, and came to realize I didn’t really care which side of the paper I worked on.”

Arriving in Philadelphia, Smith was unaware whether he’d be working for the city desk or in sports. What mattered — besides a larger paycheck — was that he was moving to an East Coast newspaper nearer the capital of American communications, New York City. Journalism was his passion rather than sports, a viewpoint that never changed.

“The guy I admire most in the world is a good reporter,” he said in No Cheering in the Press Box. “I respect a good reporter, and I’d like to be called that. I’d like to be considered good and honest and reasonably accurate. The reporter has one of the toughest jobs in the world — getting as near the truth as possible is a terribly tough job.”

With strong reporting his lodestar, Smith began in Philadelphia and was assigned to the sports beat. First as a staff writer and later as a seven-day-a-week columnist also filing event stories, Smith became a literate, witty and unavoidable presence on the Record for nine years.

Smith’s work caught the eye of Stanley Woodward, sports editor of the New York Herald Tribune, who brought Smith to New York in 1945. HIs first article was published one day before his 40th birthday. The new hire “only needed to write one story a day” — an estimated 200,000 words per year.

Over the next 21 years, until the paper folded in 1966, Smith would help enhance its reputation as “the newspaperman’s newspaper” devoted to inventive rather than pedestrian prose. Smith became the most widely syndicated sports columnist in the nation, with about 70 papers and some 20 million readers.

Besides his six columns a week, Smith also contributed articles to an array of national magazines (The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Outdoor Life, Liberty, Holiday), and he was the subject of flattering features in Newsweek, Esquire, Time, Harper’s and Life.

Collections of his columns appeared regularly, Prentice Hall launched the Red Smith Sports Series, and for nearly two decades Red Smith’s name on his syndicated column, magazine pieces and books created what in today’s marketing parlance would be called a brand, the most readily identifiable and reliable mark of distinctive work.

Ernest Hemingway devoted a scene in his novel Across the River and into the Trees (1950) to a character reading — and liking — Smith. In 1963, author Irwin Shaw sent him a letter, saying “how much I like your stuff.” Shaw then told a story: “A few years ago Hemingway was asked to name the three best books he had read that year and the cold, brilliant brute (who by that time was feuding with me as he feuded with a lot of his old friends) named books by Faulkner, you and me for his list. I couldn’t have been more pleased or more in agreement with the man.”

Shortly after this letter arrived, Smith told a Chicago reporter writing a profile, “I flinch whenever I see the word literature used in the same sentence with my name. I’m just a bum trying to make a living running a typewriter.”

In 1971, at 66, Smith signed to write a column for The New York Times, which he’d previously viewed as an institution akin to a cathedral. Smith’s work went to 500 more papers in America and abroad. He wrote four columns a week for the Times during a decade there, with his final one appearing on January 11, 1982, just four days before his death.

The years with the Times were among Smith’s most significant and productive. The Pulitzer committee finally honored him (at age 70), and magazine essays appeared in Saturday Review, Esquire, American Heritage and The New York Times Magazine.

Frugal with the first-person pronoun, he referred to himself in columns as “the tenant in this literary flophouse,” “a newspaper stiff,” “a greenhorn” and even “a rube.” Although he poked fun at himself, Smith took his craft seriously. Late in his life during an interview, he recalled being “dragooned to speak to the advertising salesmen of the Herald Tribune. I got up and told a couple of stories and said, ‘You fellas probably think I’ve got the softest job in the world. And as a matter of fact, I have. All you do is sit down and open a vein and bleed it out drop by drop.’”

During another session with a reporter, he recalled a vow he made when he moved to New York: “I made up my mind that every time I sat down to a typewriter I would slash my veins and bleed and that I’d try to make each word dance.”

Searching for the mot juste, firecracker phrase or arresting image meant that a column could take six hours to write and produce a wastebasket full of crumpled copy paper. Smith was often the last person to leave a press box, and his home office was designated “The Sweat Shop” or “Torture Chamber.” The painstaking prose never seemed labored, however. As he liked to say, “You sweat blood to make it sound so smooth, so natural, it reads as though you knocked it off while running for a bus.”

Just as he had definite demands for his own work, Smith maintained fixed opinions about sports columns. In the main, he saw himself as an entertainer. “I’ve always had the notion,” he once said, “that people go to spectator sports to have fun and then they grab the paper to read about it and have fun again.”

Similarly, he said of his beat, “These are just little games that little boys can play, and it really isn’t important to the future of civilization whether the Athletics or the Browns win. If you can accept it as entertainment, then I think that’s what spectator sports are meant to be.”

This playing-field-as-playful-place perspective kept Smith from inflating athletic contests to Armageddon battles or sports figures to Shakespearean heroes. Yet it never restricted his field of vision or panoramic view. “It can be stated as a law,” he once wrote, “that the sportswriter whose horizons are no wider than the outfield fences is a bad sportswriter, because he has no sense of proportion and no awareness of the real world around him.”

Unlike such journalists as Heywood Broun, Westbrook Pegler or James Reston, who started in sports and subsequently shifted to political writing, Smith stuck with sports, except for the occasional assignment to cover national political conventions as the sporty, competitive spectacles they used to be. The “real world,” though, kept intruding on Smith’s writing.

The lead of a column in May 1958 put world affairs in perspective at the same time when Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals was sweating to get his 3,000th hit in the major leagues:

France and Algeria heaved in ferment, South Americans chucked rocks at the goodwill ambassador from the United States, Sputnik III thrust its nose into the pathless realms of space — and the attention of some millions of baseball fans was concentrated on a grown man in flannel rompers swinging a stick on a Chicago playground called Wrigley Field.

Especially in his later years, Smith was willing to probe areas beyond the fun-and-games of sports. When he urged the United States to boycott the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow to make a foursquare stand against the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, President Jimmy Carter and other public officials paid attention and ultimately decided not to have America compete. Smith saw his stand, controversial initially, as “common decency,” telling a reporter, “How can you go over and play games with these people when they’re committing a naked act of aggression against a neighboring country?”

Increasingly, big-time sports were more than larkish games of youth, and on occasion Smith was willing to assume the role of sports conscience. As Jane Leavy pointed out in a 1978 Village Voice profile, Smith’s literary quality was just one factor in the Pulitzer Prize for commentary he won two years earlier. “Seven of the 10 columns submitted to the Pulitzer jury,” she reported, “concerned the political implications and litigations surrounding our national pastimes.”

Similar to Mark Twain’s writing as he got older, Smith’s addressed worldly problems more frequently and openly. Both writers came to realize that certain subjects demanded something more than the provocation of laughter. In Smith’s precinct, the serpentine connections between sports, money and politics clamored for analysis and appraisal, and with his advancing years, clouds kept popping up to darken the once sunny athletic fields.

Maintaining perspective and recognizing complexity were hallmarks of Smith’s approach from his first days as a columnist; it’s just that his later work, responding to the more tangled times of mammon’s dubious influence, tended to spotlight more serious concerns. Back in 1955, he began one of his obituary columns (“A Fan Named Bob Sherwood”) with a career-defending generalization before praising Sherwood’s literary and political accomplishments:

Some intellectuals deem an interest in games evidence of arrested development. . . . Theirs is a foolish snobbery that exposes their own inability to see a whole, round world in which games have a part along with politics and science and industry and art.

More diamond cutter than blacksmith, Smith tried to make phrases sparkle and all facets of a column look finished. For Smith, a new gymnasium became “a center of the perspiring arts” and Ted Williams’s spitting at baseball hecklers “a moist expression of contempt.” A famous auto race was a “twelve-hour orgy of noise and grime,” bucking broncos were “four-legged outlaws” and a former boxer “a dressy little walking-stick of a man.” A sports executive “smiled with the warmth of a brave man having splinters thrust under his fingernails,” and an outfielder jumping to make a catch “stayed aloft so long he looked like an empty uniform hanging in its locker.”

Smith playfully dismissed the sports section as a newspaper’s “toy department,” but he never wrote down to any suggested grade-school level for readers. He gave his copy a literate lift. Fishing to him was “piscicide,” “bassicide” and “perchicide.” A football tailback looked like a “frumious bandersnatch.” Knute Rockne “gave the impression that instead of dressing he just stood in a room and let clothes drop on him.”

In his last column, “Writing Less — and Better?” he worried that cutting back from four to three per week would provide him less chance to be good or to recover from what he judged an unsatisfactory effort. At age 76 and with more than 10,000 columns to his name, Smith remained hopeful of improvement and still competitive. Consummate craftsman, he always believed future words might dance with new kicks and previously untried gyrations.

Three decades before his own death, Smith remarked about tennis champion Bill Tilden, “He would have been great in any age; he lived in the age that was exactly right for him.” The same judgment could be made about the composer of that sentence. Stylish, memorable prose will find an audience regardless of how it’s delivered: on newsprint or slick paper, between covers of a book or via a computer screen. At a time when sports journalism often seems embalmed with clichés or empurpled with prose closer to parody than poetry, Smith continues to serve as an original and an exemplar.

But Smith thrived when newspapers still enjoyed their heyday and syndication of sports columns meant national stature for a New York-based writer. Today, with more and more newspapers struggling and greater emphasis on staff-written columns, the influence Smith achieved would be impossible. The success of ESPN as a multimedia enterprise helps sportswriters in major cities gain broad visibility, but the different means of distributing their views create a different kind of impact.

The spoken word, notably brash and quickly formulated, competes against the written one, with local columnists often becoming better known for what they chatter about than what they compose more deliberately for their print outlets. It’s not necessarily inferior — we’re still talking about games little boys and girls can play — but it’s clearly distinct from Smith’s earlier era of a print-dominant culture.

Stanley Woodward, who had brought Smith to New York in 1945, would later say, “In my judgment he has become the greatest of all sportswriters, by which I mean that he is better than all the ancients as well as the moderns.” The same could probably still be said today and for years to come.

Bob Schmuhl is the Annenberg-Joyce Professor of American Studies and Journalism and director of the Gallivan Program for Journalism, Ethics and Democracy at Notre Dame. This is adapted from his introduction to Making Words Dance: Reflections on Red Smith, Journalism, and Writing .

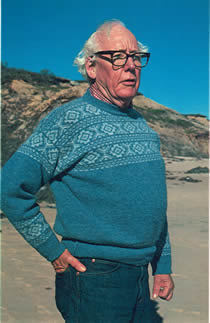

Red Smith, photographed for Notre Dame Magazine at Martha’s Vineyard in 1979.