Of all the horrific moments that haunted José Reyes Ferriz’s three years as mayor of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, the most excruciating involved the 2010 massacre of 16 teenagers and young adults at a party in Villas de Salvarcar, one of the working-class barrios of this sprawling border city. “It was a terrible, terrible ordeal,” Reyes ’88LL.M.. says of the tragedy, which stunned all of Mexico with a trauma as soul-shaking as that inflicted in the United States by the 2012 mass-shooting of first-graders at a school in Newtown, Connecticut.

The killings at Villas de Salvarcar seemed to compress into a few seconds all the mayhem, malice and madness that rampaged through the streets from 2008 to ’10, as rival drug cartels waged a war for control of borderland smuggling corridors into neighboring El Paso, Texas, a gateway to the United States.

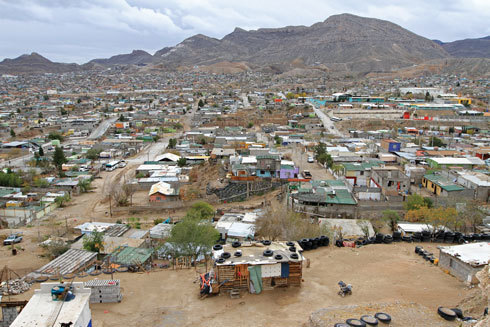

The relentless violence would devastate the city, plunging it into a maddening swirl of criminality and chaos that continued well beyond Reyes’ term in office. The violence fed on itself, as one killing triggered revenge attacks that piled on several more. It also fed on weaknesses in the city’s civic, cultural and political fabric — the deep-seated corruption, the fecklessness of the criminal justice system, the distrust of authority. An underlying factor was the grinding poverty that was commonplace in a city where a few had grown wealthy from foreign-owned assembly plants but where the living conditions of many workers in those plants compounded despair and hardened frustration.

In 2007, Juárez, with a population of about 1.5 million, had 320 murders. That number was high enough — New York, with 8 million people, counted 494 murders that year. But in 2008, as the cartel wars raged, the Juárez body count jumped to 1,623. That was just the beginning. In 2009, the figure reached 2,754 and the crime wave swelled with extortion, kidnapping and robberies at banks, convenience stores and corner groceries. In 2010, the deaths climbed to a staggering 3,622 — an average of 10 people per day.

Much of the killing was narco-terrorism — intended to annihilate and intimidate. News accounts showed bodies sprawled across bloody sidewalks, splayed across the floors of restaurants and bars, lying headless on dirt streets. Bodies hung like smashed mannequins in the open doors of vehicles struck by enough high-caliber rounds to resemble cheese shredders.

The bloodletting was a relentless assault on the spirit of ordinary people whose ability to lead ordinary lives had been ripped away. A sense of doom and danger locked people in their homes at night and made them fear eye contact during the day. It became difficult to envision a future. “What’s the point of raising good kids if they are going to kill them anyway,” said a man who worked with the father of one of the Villas de Salvarcar victims.

Several hundred thousand residents fled the city. Juárez was news around the world. Reporters reached for metaphors to measure the dimensions of the disaster. Juárez had become a war zone, they said, a killing field. It was the most dangerous city in the world. At one point, when Reyes was interviewed on CNN, a graphic called him “The Mayor of Hell.”

The mayhem came with a diabolical soundtrack. Cartel hit men broke into police radio frequencies to play narco-corridos as a means of announcing another execution. Corridos, a form of Mexican ballad with a bouncy accordion beat, had long celebrated a Robin Hood spirit of social justice and defiance of corrupt authority. But some of the songs had mutated into hardcore anthems for sociopaths. One of them proclaims: “With an AK-47 and a bazooka on our backs, blowing off heads that cross our path. We’re bloodthirsty and crazy. And we love to kill!”

The killings at Villas de Salvarcar began when members of the Barrio Azteca gang arrived in two vehicles and sealed off both ends of a street lined with tiny houses. They began firing, believing their victims to be members of the hated rival gang, the Artistas Asesinos — the Murder Artists — sometimes known as AA.

It was a horrendous case of mistaken identity. The victims had nothing to do with the gang. Some of them were members of a team celebrating their tournament victory in the AA league of American football. “They were good kids,” says Reyes. “Kids you could be proud of.”

A dream of flying above it all

If Aeromexico had been hiring in 1982 when Reyes turned 21, he might have flown high above the madness that seized his hometown 25 years later. He was already a licensed pilot for a large Mexican glass company, and he dreamed of working for the airline. But as the peso slid and recession hit Mexico, the airlines shed jobs. So Reyes went on to make his career in law and politics in the city where his father was mayor from 1980 to ’83.

When José was a small boy, his father rigged the television set so that José and his younger brother and sister could watch only the El Paso stations. Under the tutelage of Sesame Street, Tom and Jerry, Three’s Company and Lost in Space, he learned to speak fluent English with an American accent. He attended Catholic schools for six years and then moved on to public high school and the public university in Juárez , where he got his law degree.

Reyes is a man of calm self-confidence who dresses in Italian suits and, as a writer for Foreign Policy magazine put it, “exudes an urbane and learned sensibility.” He says his training as a pilot helped prepare him for dealing with the turbulence and tumult he encountered as mayor. “A pilot can’t let himself be overwhelmed by what is happening in his immediate surroundings,” he says. "When you are able to look ahead and see things from a distance, you have a better idea of what you need to do.”

Like his father, Reyes is a member of the Institutional Revolutionary Party or PRI. He says he is drawn to the party’s center-left commitment to social programs. He also says he’s too liberal to be in the rival National Action Party. Known as the PAN, for its initials in Spanish, it is best known in the United States as the political home of Vicente Fox, the charismatic former Coca-Cola executive whose dramatic victory in the presidential race of 2000 ended seven decades of uninterrupted, authoritarian PRI rule.

In 2001, after the Juárez mayoral election was annulled for irregularities, the state legislature named Reyes, who had not been a candidate, to serve as provisional mayor for nine months until another election could be arranged. He found that he liked the challenge and enjoyed solving problems. So in 2007 he ran for the office, winning easily with a campaign that promised honesty, efficiency and competence.

“Corruption and disorder come when the rules are unclear and procedures are complicated,” he says. Several of his ideas were aimed at bringing order to the chaotic streets. He wanted rules to stop bus drivers from making wild cat stops wherever they wanted. He imposed regulations on the city’s traffic police to end the notorious shakedowns for phantom violations. He had the city confiscate several thousand used cars that people had smuggled across the border.

Reyes called his program AMOR, the Spanish acronym for Municipal Accord for Order and Respect. But the gangsters’ mocking defiance of authority made the campaign pledges impossibly out of place. As the city crumbled under the intense assault of mounting cartel violence that shook the entire nation and stirred fears in Washington of a failed state on the southern border, Reyes held on. He battled not only insurgent cartel gangsters but also rampant corruption in the city police, a Chihuahua governor who remained strangely disengaged from events in the state’s largest city, and a state attorney general with a maddening habit of failing to prosecute serious criminals.

The mayor who had promised order and respect would spend his term riding the tiger of narco-terror, seeking to preserve sanity and survival. University of Texas professor Ricardo Ainslie, in his tense The Fight to Save Juárez, would write that as he was doing his reporting for the book, “The thought occurred to me that I was watching the most beleaguered man in all of Mexico.”

Through it all, Reyes insisted on maintaining a routine that included teaching classes at the public university in Juárez, where he had been dean of the program on international trade. That position drew on his training at the Notre Dame Law School’s campus in London, where he received a master’s degree in international law with a concentration on trade. It also anticipated his current line of work, far removed from his home on the border. He now lives in Washington, D.C., where he has a private practice advising corporations involved in international trade.

Rough initiation

Reyes received what he calls his “initiation” into the city’s new circumstances a few weeks after his October 2007 inauguration, when he announced a policy to fight the theft of cars from Juárez streets. Thieves were targeting cars that ordinary citizens drove regularly to El Paso, establishing a clean record in the computers operated by Customs and Border Patrol agents at the port of entry. Such cars were less likely to be selected for secondary inspection from the thousands that passed through every day, making them ideal for brief drug-smuggling missions.

Reyes announced a policy to encourage reporting thefts immediately to city authorities, who would then share the information with other law enforcement agencies, including the Americans on the other side of the bridges that span the Rio Grande.

The cartel response came fast and hard. In the clear light of day about a dozen men armed with assault rifles stepped out of SUVs and took up positions outside his office. It was brazen intimidation aimed at a mayor who was protected by a small, lightly armed team of bodyguards. Reyes had little choice but to back off. “When the pushback is that strong, you know you can’t fight that war,” he would say later. “The city has a budget of $250 million. These guys have a multibillion dollar business.”

The criminal organizations preparing for war in early 2008 were the Sinaloa cartel and the Juárez cartel. Both are legendary for their wealth, their ruthlessness and their ability to buy protection with the old Mexican choice: plata o plomo — silver or lead — a bribe or a bullet.

Before his arrest in February, the boss of the Sinaloa cartel was Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, who had been described by the U.S. Treasury Department as “the world’s most powerful drug trafficker.” He was famed for his fondness for burrowing into the United States with elaborate narco-tunnels outfitted with air-conditioning and rail tracks for ease of movement. Guzman had a place on the Forbes list of billionaires until 2013, when the magazine concluded that he was paying so much in bribes that his fortune had likely slipped below the billion-dollar threshold.

The Juárez cartel is run by the successors of Amado Carrillo, who approached the U.S. market from a different angle. During the height of the U.S. cocaine fad in the 1980s, he had 737s loaded with the white powder flown to the Juárez airport. He was also adept at corrupting Mexican authorities. In 1997, shortly after Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo named a Mexican Army general to head the National Institute to Combat Drugs — a move hailed by U.S drug czar Barry McCaffrey, who praised the general as “a guy of absolute unquestioned integrity” — the general was discovered to be on Carrillo’s payroll.

In addition to buying influence at all levels, the cartels employ thousands: pilots, drivers, distributors, stash house attendants, lookouts, tunnel engineers and “burros” who carry the drugs across the border on their backs. Others are couriers who carry back to Mexico some of the billions paid every year by drug customers in the United States. At an El Paso port of entry in 2008, agents became suspicious at the jittery behavior of a Mexican immigrant to the United States who was driving to Mexico from Kansas City. When they sent his Ford Expedition for secondary inspection, they found $1.9 million in cash hidden in the doors.

U.S. law enforcement intercepts only a small portion — often estimated at 10 percent — of the drugs heading north. Early in 2008, officials arrested Saulo Reyes Gamboa, who had been public safety director in the Juárez police department under Reyes’ predecessor. They announced that he had been arrested “after he allegedly paid a person who he believed to be a corrupt federal officer to facilitate the smuggling of drug loads through the international port of entry.” Authorities seized nearly a ton of marijuana that Reyes Gamboa had stashed in an El Paso house.

2008 — the beginning of the war

The cartel war erupted three months after Reyes was inaugurated as mayor. It was sparked by the Sinaloa operatives who began assassinating Juárez policemen in order to claim control of drug-smuggling territory. Their campaign included signs in public places that La Gente Nueva — the new people from Sinaloa — would eliminate all resistance. One sign listed the names of five policemen “who did not believe” and had therefore been murdered. It also named 17 policemen “who still do not believe” and were marked for elimination.

A blood bath drenched the city. At the end of March, with the year’s body count already passing 200 and the city in an uproar, Mexican President Felipe Calderón sent in the country’s army. Several thousand troops arrived in convoys of olive-drab Humvees and pickups and set up checkpoints around the city to intercept weapons and drugs. Reyes applauded as Interior Secretary Juan Camilo Mouriño declared firmly, “In this battle, no group will be able to withstand the government’s force.”

Reyes believed federal intervention was essential. “Neither the municipal government nor the state government is capable of taking on organized crime,” he says. He was convinced that the federal forces would provide him breathing room to clean out the badly corrupted ranks of the police force. He launched that effort with “confidence tests” — using lie detectors and psychological evaluations — that led to the firings or resignations of hundreds of officers.

“We know that all of the police forces have been infiltrated by bad elements, and our job is to identify these persons and get them out of the municipal police,” Reyes said at a press conference. He began a recruiting drive across Mexico, offering some of the highest police wages in the country and incentives that included help with financing the purchase of a home.

Reyes also sought to restore his city’s shattered morale. He presided over an awards ceremony that capped the competition among primary school choral groups to provide the best rendering of a new song that hailed Juárez as “the best city of the borderlands,” one built by “courageous people to overcome any adversity and always grow in the face of the storm.”

Complaints of army excess

The people of Juárez found no tranquility in the massive military presence. Their initial relief soon gave way to loud public grumbling that the searches for drugs and thugs were ham-handed, indiscriminate and often brutal. “When the army first arrived, the people received them well; they applauded them,” said Rocío Gallegos, editor at El Diario de Juárez, the city’s leading daily newspaper. “But it was just a matter of days before the people began reporting abuses.”

The most outspoken critic was Gustavo de la Rosa, an official of the state’s human rights commission, who complained that the army had snatched innocent people off the streets and tortured them to extract confessions. "Abu Ghraib would be a kindergarten compared to the military camp here in Ciudad Juárez,” he said.

Instead of diminishing, the criminality expanded. There was frequent talk that President Calderón had stirred a hornet’s nest. Kidnapping, car-jacking, bank robberies and convenience-store holdups spread like a virulent infection. Perhaps most insidious was a wave of extortions. Sinister thugs swaggered into restaurants, bars, bakeries, construction sites and even schools, demanding the payment of protection money.

Alfredo Corchado, a native of El Paso, covered the story for The Dallas Morning News. He assessed its toll in his book Midnight in Mexico: “Juárez was dying. Our favorite bars and restaurants had been shuttered. Many establishments closed down rather than risk the consequences of not paying protection money. Cartels torched businesses that failed to pay, leaving them in cinders. Many business owners simply fled with their families and set up shop on U.S. soil, where they waited for peace to return.”

Reyes’ frustrations grew because of his tense relationship with the state government, based 215 miles away in the city of Chihuahua. He believes his work with President Calderón, a PANista, angered the governor, who is a member of the PRI. Even more aggravating was the listless performance of the state attorney general, Patricia Gonzalez. “We would arrest people one day — catch them red-handed — and she would release them the next,” says Reyes.

Of the thousands of murder files that piled up on Gonzalez’s desk, only a few were investigated and a trivial number produced convictions. That failure is endemic in Mexico. In 2012, The Washington Post reported that “two percent of reported crimes in Mexico lead to convictions.”

2009 — death threats

Throughout Reyes’ tenure as mayor, the cartels sought to destabilize and terrorize the Juárez police force, eliminating officers they could not corrupt. In 2009, the second-ranking police officer, Sacramento Perez, was murdered by a Juárez cartel commando team that attacked in three vehicles at a busy intersection. That was quickly followed by a threat to kill a policeman every 48 hours if police chief Roberto Orduño did not resign. At a press conference Reyes said he and Orduño would stand firm: “We will not be terrorized by these criminals.” After three other officers were killed, Reyes and Orduño appeared at another press conference. This time Orduño announced that in order to avert more killing he was stepping down.

As always, Reyes was determined not to reveal his private anxieties. He said the resignation was not surrender but an act of loyalty. “It’s understandable that the major’s first concern was his officers,” said Reyes, who also received death threats. At one point a sign was placed next to the severed head of a dog. Its message: “José Reyes, one more dog; you have two weeks left to live.”

Despite the danger, Reyes took heat from critics who chafed that he owned a house in El Paso and suggested he was fleeing there for safety. Reyes responded that his family was indeed in El Paso, where they had owned a house for years, but he was living and sleeping in Juárez. When Ricardo Ainslie raised the issue during an interview, Reyes took the author to his Juárez residence. In his book, which was published well after Reyes left office, Ainslie described that house as showing clear evidence of daily living and took special note of the steel fortifications Reyes had installed as a defense against an assault.

Reyes shrugged off the criticism as the work of political foes and their allies in the tabloid press and blogosphere. He rejected advice from staff that he prove where he was living. “My people told me you should do an event in your home,” he says. “But I didn’t want to show the security measures I had. If someone knows you have them, they are ineffective.”

Controversial maquiladoras

While Reyes worried about the depletion of his police force by resignation, assassination and termination, he also watched with alarm as the recession in the United States struck at the maquiladora industry that was the backbone of the Juárez economy.

Some 300 of the assembly plants operated in the city, employing more than 200,000 workers. The maquiladoras received parts and materials imported duty-free from the United States and sent finished products back across the border.

In Juárez, the automobile industry was particularly important, with Delphi, the car parts giant, and others industries hiring workers to assemble wiring systems, sound systems and seats. Within weeks of the financial downturn north of the border, the layoffs began mounting in Juárez. By mid-2009, tens of thousands of workers had lost their jobs. Many of them left the city, joining the exodus of those who fled the killing. Thousands of homes lay vacant. Fearing that the violence would feed the downward cycle with more maquiladora closings, Reyes went to work to keep them in town. “I was constantly in touch with them — reassuring them, keeping them informed of what we were doing,” he says.

“The maquilas are very footloose,” Reyes adds. Few have made big capital investments in the city. Many don’t own their buildings. They bring in their management — who like to go home at night to El Paso — and their machinery. They can operate under a “shelter” plan offered by Mexican companies that provide the workers and handle the paperwork.

“I became preoccupied with keeping them in the city, because without them Juárez would be a ghost town,” Reyes says. With them, the city became a boomtown of low-paying industrial labor. The industry surged after the North American Free Trade Agreement took effect in 1994, making Mexico, which offers easy access to the American market, more attractive for labor-intensive manufacturers not only from the United States but also from Asia and Europe. Mexico’s weak enforcement of labor laws and environmental laws enhanced the attraction.

Juárez’s political and economic leaders long ago saw the maquiladora industry as the heart of their economy. They have wooed it and carefully tended to its needs. They built roads and utilities to serve the industrial parks where the plants clustered. They cheered as the maquiladoras sent recruiters across Mexico to attract workers, loading up buses in such faraway states as Veracruz and Chiapas with young people eager for work in the borderlands.

“But we neglected the social issues,” says Reyes. “That was a big mistake.”

Perhaps the biggest neglect was the failure to provide decent communities for the tens of thousands of newcomers who occupied vacant land on the edge of town. Squatter camps, improvised with cardboard and pallets discarded by the factories, sprouted chaotically. City leaders turned a blind eye to the confusion, which came to symbolize their troubled prosperity. Eventually the city began to pave the main streets and provide basic services to the sprawling slums, which were called the dormitories of the maquiladoras.

Every morning and then again for the second shift, tens of thousands of workers leave their ramshackle homes and board hundreds of ancient American school buses for the trip to the factories. Most earn about $60 for a work week of 45 hours. That’s what 26-year-old Jaime Gutierrez said he expects to make at the Rio Bravo Electronics plant owned by Delphi. Talking outside the plant at the end of 2013, he said he recently left his job at a Taiwanese-owned television assembly plant because it paid 50 pesos (about $4) less per week.

With his wage, Gutierrez tries to meet his responsibilities to his wife and child. His biggest expense is a bargain — about $80 a month to buy a tiny, three-room home constructed by a government program that in recent years has built intensively in Juárez, helping to correct the previous years of shantytown neglect. However, a Sunday lunch outing to one of the city’s McDonald’s, Burger Kings or Wendy’s would be an extravagance, costing well over a day’s wage. Maria Teresa Almada, who runs a recreational and social program for young people in marginalized areas, says most workers “_no viven; sobreviven._” “They don’t live. They survive.”

It has been that way for a long time. In 1995, the mayor of Juárez told The New York Times, “We’re creating an enormous mass of wretchedly poor people.” Citing the cozy tax arrangement that collects little in taxes from the industry but sends nearly all of what’s gathered to Mexico City, he said, “Our problem is, where is the money going to come from to provide services for all these people?”

The Nini life

Juárez is the home of tens of thousands of aimless young men called “Ninis.” That is an abbreviation for those who ni estudian, ni trabajan, neither study nor work. They are rootless, often from broken families that migrated from distant places. Many are raised by single mothers struggling in low-wage jobs.

Padre Aristeo Baca, a parish priest who works with the poor, says the gangs offer such young men the opportunity to attach themselves to the rebel world of the narco-corridos, the songs that celebrate el valiente — the tough guy with a gold chain around his neck and a silver-plated gun in his belt, striking the pose of one who is defiantly wild, ruthless and irresistible to women.

“It is called the narco-culture,” says Padre Baca. “It shows them a life of money, women, alcohol and drugs. It is a mentality of doing whatever you want, like a king. They say, ‘I’d rather live one year as a king than 50 years as a poor man.’”

During the Reyes administration, competition among the gangs for street-level drug sales led to many of the Juárez murders. Many other murders were assassinations carried out by young gang members who became sicarios, hit men willing to kill for a few pesos. Said El Diario editor Raul Gómez, “Sometimes they kill practically for a plate of food.”

The depraved killings in Juárez are not new. The city was notorious in the 1990s for a wave of several hundred brutal slayings of young women, many of them working in the maquiladora industry. Only a handful of the murders were solved.

Reyes would like to see greater efforts by the maquiladora industry to improve life in Juárez. “I think they should do more,” he says. “I think they need to do more. I think they need to be more in touch with the city.” He says the picture now is mixed, observing that while some plant managers are under pressure to maximize the bottom line, others have at least some room to take action. “Some of them look at ways to make a difference in the lives of their employees,” he says. He lists day care, subsidized meals, infirmaries and educational programs as extras provided by plants who want to do more than simply what is required by law.

However, he adds a caveat about the facts of maquiladora life in the age of globalization. “It’s a market issue. It’s everybody for himself.”

Reyes says one of his proudest accomplishments as mayor was his wooing of Foxconn, the Taiwanese company best known for assembling the iPhone in China. Juárez won a competition that included other Mexican cities and Brazil. The result is a massive plant in the desert flatlands just west of the city that employs more than 5,000 workers who assemble Dell computers and other products. Foxconn built the plant yards from the Mexican-U.S. border, near a new port of entry that maximizes speed of shipment to U.S. consumers.

2010 — Villas de Salvarcar and the fight for life

When President Calderón heard the first reports of the massacre at Villas de Salvarcar while traveling in Japan, he speculated publicly that it was a typical gang-style settling of accounts. That careless insult was salt in the wounds of the Villas de Salvarcar community. Chastened by public condemnation, Calderón looked for a way to make amends. He came to Juárez and joined Reyes in a meeting with residents of the shattered community. Both men received bitter criticism for the lawlessness that had produced the tragedy.

Reyes had been trying to get federal support for the sort of social programs he had observed during visits to Colombia, whose stability had also been threatened by drug mafias. With Calderón’s support, a program was launched under the name Todos Somos Juárez — We Are All Juárez.

Today Villas de Salvarcar is home to a public library and a football field with artificial turf. There are many such facilities in Juárez, along with new schools, and recreational and cultural programs aimed at providing children an alternative to the street life and a vision of a hopeful future. The city also has 50 new daycare centers. Reyes says he had hoped to build 50 more but “the money ran out.” The needs are so vast that even the expenditure of several hundred million dollars could only begin to meet them.

Four years after the massacre and six years after the drug war madness began, peace has begun to return to Juárez. The city recorded 485 murders in 2013. At his shop in the Mercado Juárez, which is jammed with stacks of serapes and shelves of leather, ceramics and glassware, Gabriel Cazares says the tourists who used to fill the block-long aisles are slowly returning.

Cazares picks up a blue T-shirt with the slogan of a campaign the Reyes administration launched when times were terrible. “_Amor por Juárez_,” it reads, a slogan Reyes says was an imitation of the I (Heart) NY campaign launched in 1977, when that city was demoralized by rampant street crime and a soaring murder rate. A businessman who closed his restaurant in 2010, fleeing to El Paso after thugs attempted to kidnap his wife, has returned. “The drug dealers have receded,” he told The New York Times. “It’s not cool anymore to be a narco.”

And so the green shoots of life and laughter are reasserting themselves on city blocks still charred from the extortionists’ flames. Some people say the new, mandatory life sentence for kidnapping has aided the recovery.

In late 2013, the Chihuahua attorney general’s office took out a two-page ad in El Diario de Juárez, touting successful prosecutions of kidnappers, extortionists and murderers. The ad also declared that the state now has well-trained investigators and prosecutors and “above all a police force unified in the prevention and investigation of crime.”

But several prominent members of the community warned in interviews that the cartels’ thriving business of selling drugs to the United States, the disengagement of many youth, the family dysfunction and the narco culture still lurk in the shadows.

Meanwhile, maquiladora representatives were warning that the federal government’s proposal to raise taxes on the factories in order to support social programs would have a negative effect on the industry in a country where job creation is a major social and political imperative.

Back in 2010, when Juárez was ablaze with criminal anarchy, Mexican legal scholar Edgardo Buscaglia warned that such lawlessness would be the future of Mexico unless the country’s political and business rallied behind a “patriotic pact” similar to what developed years earlier in Colombia, when cocaine mafias threatened that country’s governability. Buscaglia said history has shown that effective measures are not taken until the “elites who created this monster begin to be victims of their own creation and see their families massacred, their patrimony taken, their private clubs bombed.”

As José Reyes looks back on his time in office, he speaks of it as “a perfect storm” of cartel ruthlessness, nini rootlessness, shockwaves from the recession in the United States and the corruption of Mexican institutions. He draws on his experience as a pilot to extend the metaphor. “Being mayor was like taking a plane through a storm. The ride was rough, but we made it through. Sometimes I wonder how.” Under Mexican law, he could not seek re-election, but he acknowledges that he would not have wanted to do so anyway.

Padre Baca offers this view of José Reyes Ferriz and his term in office. “He is an honest man, an honorable man. I see him as a man of good will who wanted to do good things. He did some good things. But the circumstances, the climate of violence, did not allow him to do what he had hoped to do.”

Jerry Kammer began writing about Mexico in 1986, as Northern Mexico correspondent for the Arizona Republic. A series about the assembly plants known as maquiladoras that he wrote with Sandy Tolan won the 1990 Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for international reporting. In 2006 he won a Pulitzer Prize for his work on a Copley News Service team that exposed a bribery-for-earmarks scandal whose central figure was U.S. Rep. Randy “Duke” Cunningham of California. He is now a senior research fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington, D.C., and lives in Rockville, Maryland.