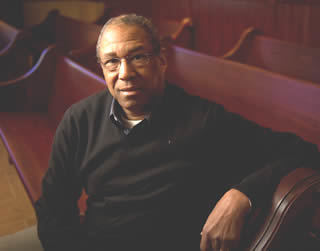

Arthur McFarland ’70 arrived at Notre Dame in autumn 1966 from Charleston, South Carolina, one of about a dozen black students in his freshman class. He was a graduate of Charleston’s prestigious Bishop England High School, named for a man who embodied the American Catholic Church’s ambivalent and ambiguous attitude toward blacks.

According to Cyprian Davis, the black Benedictine monk who in 1990 published The History of Black Catholics in the United States, John England was at once “one of the most brilliant and innovative bishops of the pre-Civil War period” and, where the great moral issue of his day was concerned, one of the most frustrating.

A native of Ireland who was appointed to the see of Charleston in 1820, England started a school for the children of free black families — it was closed after white South Carolinians rioted in opposition — and consistently maintained that he was personally opposed to the existence of slavery. Nevertheless, after Pope Gregory XVI in 1839 published an apostolic letter condemning the slave trade, England seemed to go out of his way in his diocesan newspaper to assure defenders of America’s Southern slave system that the pope’s words hadn’t been intended for them.

Davis quotes the judgment of England biographer Peter Clarke: “England, it would seem, accepted the structure of the society that he found in the South. In this policy of acceptance, he allowed the church and himself not to be considered as opponents of slavery.”

Nothing was ambiguous or ambivalent about Art McFarland, however. He arrived at Notre Dame with a pedigree in civil rights, having been arrested three times in demonstrations and civil disobedience campaigns in Charleston. And in autumn 1964, as he was entering his junior year of high school, he had become one of nine black students to integrate Bishop England.

Like Jackie Robinson in baseball and the Little Rock 9 in public education, McFarland and his fellows were selected for their roles. Selected not just for their academic and intellectual abilities but also for their characters, their abilities to handle the social pressures that went with being “the first.”

“I guess we were carrying the race on our shoulders,” says McFarland, now 63 and a respected veteran of the bar and the bench in his hometown.

Carrying the race, and helping to carry the Church, into the modern era.

The Irish, the Italians, the Poles, the Mexicans — it’s second nature to think of members of these ethnic groups as Catholic. So much so that group and faith are inextricably linked in the imagination of the American public.

But black Catholics? That does not compute. In part it’s because of sheer numbers. Black Catholics number only 2.5 million, according to the best estimate of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. That’s a little over 3 percent of the country’s 68 million Catholics and about 7 percent of its 39.9 million blacks.

And yet, as Cyprian Davis observes in his book, blacks have been part of the U.S. Catholic faithful from the start, “add[ing] another essential perspective to the meaning of the word ‘Catholic’ and to the understanding of the American Catholic church.”

Two gatherings on the Notre Dame campus last spring called attention to that presence and perspective. From May 3-5, six black bishops and a sizable complement of priests met in Geddes Hall in a symposium, sponsored by the National Black Catholic Congress, on fostering vocations to the priesthood in the African-American community. On May 6, the Catholic Cultural Diversity Network began a three-day convocation that brought together representatives of the rainbow of ethnic groups that make up the American church in the presence of some two dozen bishops and the Vatican’s apostolic nuncio — its ambassador — to the United States, the Most Rev. Archbishop Pietro Sambi.

Both gatherings were brought to the campus through the efforts of Associate Provost Donald Pope-Davis and were supported financially, logistically and spiritually by the University’s Institute for Church Life.

Not only were these events living demonstrations of Notre Dame’s commitment to diversity, Pope-Davis says, but they also were emblematic of Notre Dame’s determination to be the place “where the church is doing its thinking.”

For Arthur McFarland, Catholicism was not the faith of his fathers — or maybe more important, of his mother, Thomasina, a devout member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church who nevertheless sent all of her and husband Joe’s nine children to Catholic school. In the segregated Charleston of McFarland’s youth, that meant Immaculate Conception School, which was staffed by the Oblate Sisters of Providence, an order of black nuns based in Baltimore. Immaculate Conception, he says, “was an evangelizing opportunity for the church in the black community.”

McFarland became a Catholic in the sixth grade. Counting pre-kindergarten and kindergarten, he had had “eight years of exposure” to Catholicism. “At that time,” he says, “they used to teach us that Catholicism was the one true religion. As a youngster, I was sold on that.”

To be Catholic was to be viewed in the black community as “elitist,” even though, McFarland points out, his father was a janitor and his family lived in a housing project. In part, that was because Catholics generally were a relatively small portion of the population in South Carolina and an even smaller portion of the black population.

Segregation was premised on notions of white superiority and black inferiority, and those presumptions followed McFarland to Bishop England. Initially, he said, he was placed in a lower academic track; after his first six weeks, he was transferred to the honors track.

He credits the Oblate Sisters of Providence for his excellent preparation. “The Oblates were strict!” he says — strict in their academic demands and strict in discipline. Ultimately, he says, “much of what those Oblate Sisters gave us was superior” to what he found at the previously all-white Bishop England.

Margo Butler is 76 and, like her parents before her, has been a Catholic since the cradle. She lives with her husband in a two-story, red-brick Georgian home in Evanston, Illinois, about half a dozen blocks west of Saint Nicholas Catholic Church, where she is a member of the parish finance council and is, as she says of her paternal grandmother, one of those people who is there “whenever they open the church doors.”

But Butler’s involvements in the church go beyond Saint Nick’s. In the late 1990s, she organized the Evanston Area Black Catholics, a group that sought to bring together blacks from Chicago’s North Shore communities who wanted a Catholic experience which also affirmed their African-American culture.

Butler was born and reared in Evanston but, like her mother, attended school through eighth grade at the Illinois Technical School for Colored Girls, a Catholic boarding school at 49th Street and Prairie Avenue on Chicago’s South Side.

Run by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, an order made up mainly of Irish and Irish-American women, the school was thoroughly Catholic but also, Butler says, sensitive to and respectful of its students’ ethnicity.

“I probably learned more about black history in that school than anywhere else I’ve been,” Butler says. “Those women were on target. They wanted to prepare us as best they could for the world they knew we would go into. We were taught black history and black poems. We learned about the [Harlem] Renaissance.”

She recalled being marched on Saturdays to the Regal Theater, the showplace of black Chicago at that time, to see such performers as composer-bandleader Duke Ellington and his orchestra.

“Every Saturday morning they would read the list of who was good and could go to the show,” she says. “We would walk to the theatre. No candy was allowed — so there could be no wrappers left on the floors to reflect badly on the Sisters.”

None of this cultural sensitivity carried over to the liturgy of the time — what Butler calls “standard pre-Vatican II Latin.” Nor was there any mention of black saints or holy people such as Martin de Porres, who later was canonized.

After eighth grade, Butler attended the local public high school in Evanston and “sort of fell away from the Church.” She returned to it after her marriage in 1952 and sent her children to Catholic schools.

She fell away again in 1968. She remembers the day precisely. It was April 7, the Sunday after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. She went to Mass, “three children in tow,” at Saint Athanasius Church in Evanston, her parish at the time.

“Nobody,” she recalls, “said a word about Dr. King’s assassination. So when we left that Sunday, I never went back.”

Years later, she says, after she had returned to active church attendance and begun organizing the Evanston Area Black Catholics, she met several other black people who had experienced the same sense of isolation and non-recognition on that same Sunday.

Butler says it is that invisibility, that non-recognition, rather than the older, cruder types of discrimination she hears of from “some of the old-timers in Chicago” — being forced to sit in back pews, for example — that has characterized her experience of discrimination in the church. And that is what she has tried to address through her work with the Evanston group, the Chicago Archdiocesan Office for Black Catholics and the National Black Catholic Congress.

Hers has been an effort to lift up the black Catholic experience and black culture and have them recognized within the wider church — both locally and nationally.

Brian Lewis did something that sounds impossible: He went through four years at Notre Dame, graduating in 1997 with a degree in theology, and remained the Protestant that he was throughout his childhood and when he arrived at du Lac. It wasn’t until a few years after graduation, while he was working in Wichita as a newspaper reporter, that he became a Catholic. Crucially, it was a black Catholic church, Holy Savior, that clinched the deal in Lewis’ conversion. But it was at Notre Dame that the process began.

“I spent a semester in Jerusalem,” he says. “And I think [I] was probably moving toward becoming Catholic. Just to see the churches there and being exposed to things I hadn’t been exposed to before, especially to see the icons and the Orthodox churches in Jerusalem — that was something really eye-catching. Seeing kind of the worldwide Catholic Church in the Holy Land — that was laying the foundation for becoming Catholic later on.”

His classroom study of theology also was a powerful influence. Theological studies fostered a “more intellectual way of looking at the Bible,” as opposed to the approach he had been exposed to previously, mainly in Baptist churches, which treated the Bible “almost as if [it] is perfect.”

It was, he says, “a whole different way of looking at scripture . . . more academic, more rigorous.” After those studies, Lewis found he could no longer feel as comfortable in the Baptist churches in which he had grown up.

Still, it was not until he was working on an article about Holy Savior Parish in Wichita that he felt the call to Catholicism. Based on a few Masses he attended in dorms while he was a Notre Dame student, Lewis says, he had “a certain expectation” about what Catholic liturgy and worship entailed.

Holy Savior upended those expectations. Its choirs sang music that resonated with him, music familiar from his Baptist upbringing. The artwork and statuary in the church was identifiably black. “It was a tradition I was used to, but it was Catholic,” Lewis says.

He can’t say that he wouldn’t have become Catholic but for Holy Savior, but the fact that it was both Catholic and black made a huge difference. Indeed, that combination exemplifies one of the things Lewis likes about the Catholic Church: It is fundamentally the same everywhere — in liturgy, in beliefs — but also different, accommodating many cultures.

Today, Lewis, 35, is back in South Bend and worships regularly at Saint Augustine Church, a multiracial west side parish staffed by Holy Cross priests and with a mission to affirm African-American culture. Lewis sings in the choir and is a lector as well.

The Catholic Church, he says, “feels like the right church for me.”

Sheila Bourelly says she has been “in and out of the Church a lot” in her 68 years. Right now she is out. The main reason: the child sex abuse scandal in the Church, and the response of Church authorities to it.

Bourelly, a retired social worker, worked for many years for Catholic Charities of Chicago in child protective services.

“When they put out that list of names [of abusers] for the archdiocese, I had worked with so many of those priests,” she says. “I felt so betrayed. When you’ve spent years protecting children — and for your church. Going up in housing projects and removing kids. . . .”

The Catholic Church has been Bourelly’s home since before she formally became a member in eighth grade, back in the mid-1950s. Her parents, whom she describes as “unchurched,” sent her to Holy Angels Parish school on the South Side of Chicago. This was at the insistence of an uncle, who had had contact with Catholic education while living in New York and who also recognized that, in the Chicago of that time, it was an advantage to be Catholic to get ahead politically and in business.

So thoroughly did Bourelly blend in at Holy Angels that it wasn’t noticed that she wasn’t formally a Catholic until she was in eighth grade. In truth, she says, “I already was one. I just got baptized. But I was already thoroughly formed in the Church.”

She went on to a Catholic girls high school in Chicago’s North Side, then to Presentation College in Aberdeen, South Dakota, for her first year of college. She ended up earning a bachelor’s degree in social work at Chicago’s Roosevelt University and later earned a master’s in divinity at Loyola University Chicago.

For about eight years in the 1990s and early 2000s, Bourelly published Deliverance, a newsletter for black Catholics in Chicago. In addition to her Catholic Charities job, she was active in evangelization in Chicago’s black communities. Like Margo Butler, she wanted to see African-American culture reflected in the life and works of the church.

Now, however, from her retirement home in Cassopolis, Michigan, she reflects on the church and the black community and says, “I’m not sure what it means now to be a black Catholic.” Figuring that out, “re-examining what is my place,” is part of a search in which she is engaged at this inflection point in her life.

What she knows for sure is this: “I’m as Catholic as I can be. All of my enriched experiences come from the Church. Not only my concept of God but my understanding of myself.”

Eventually she expects she’ll be back in the Church, even though for the moment her view of it has been “shattered.”

My own experience: Cradle Catholic. Second of nine children born to a black Catholic couple from a small town in east Texas. Family roots on both sides were in Louisiana, where Catholicism is as common among blacks as Spanish moss on the trees. Nevertheless, my father, Wilbert Wycliff, was a convert. An only child, he was raised in a household with a Catholic father and a Baptist mother, and grew up essentially unchurched.

My mother, Emily Wycliff, the second of 10 children in her family, was Catholic from the start. While most of her education was in the segregated public schools of Dayton, Texas, she got the benefit of a few years of Catholic education in the nearby black settlement of Ames, thanks to an aunt who was a member of the New Orleans-based Sisters of the Holy Family.

The turning point in my life — and in our entire family’s life as Catholics — was in 1954 when I was 7 and about to enter second grade. That’s when my dad, unable to find decent work in Texas, went to work for the federal government, teaching vocational skills to inmates in federal prisons. We moved to the eastern Kentucky city of Ashland, and there became the first black members of the sole Catholic parish in town, Holy Family. My sisters and brothers and I were the first black children to attend the parish school.

Mother has told me several times of the trepidation she felt on taking us to school the first day. She had heard of white people “stoning” black children attempting to integrate public schools in another part of Kentucky. “I thought they might stone me.”

She needn’t have worried. The pastor, Monsignor Declan Carroll, had prepared the way, warning at Sunday Mass that anyone who showed the new “colored” family in the parish anything less than a gracious welcome would have him to deal with. After a tense few minutes of waiting along with other mothers bringing their children to school, one woman approached my mother, smiled and asked the name of her daughter, my sister Karen. When mother told her, “Karen Wycliff,” the lady replied, “Why that’s my daughter’s name, too! Karen Horgan, meet Karen Wycliff.” That lady, Virginia Horgan, remains a hero to mother, who always says, “You’ll never know what a smile can mean to a person.”

The ice having been thus broken, the Wycliffs went on to be happy and included members of Holy Family Parish. My older brother, Francois, and I became altar boys. Karen became the “mascot” of the Holy Family High School “Fighting Irish” cheerleading squad. Mother became active in the Mother’s Club. And Daddy, sponsored by several colleagues from the prison staff who also were Holy Family parishioners, joined the Knights of Columbus.

Mother and Dad are now 88 and 91, respectively. Whenever we all get together — as we did in early July to bury a too-soon-gone Francois — conversation at some point always turns to what Karen calls those “magical years” in Ashland and the good people of Holy Family Parish.

Some years ago, at a gathering whose name I can’t recall, I said that all of the good things which have happened to me in my life stemmed from my being Catholic. I might qualify that statement a little bit now, but it is still essentially true.

My Catholic education, from second grade through college at Notre Dame, has been the greatest blessing of all. But at a more fundamental level, the Catholic intellectual tradition and way of thinking — seeing the world in sacramental terms, examining one’s life in terms of grace and sin, attempting always to harmonize faith and reason — have provided a basis for thinking intelligently about the world and for engaging respectfully with other worldviews.

I share more than a little of Sheila Bourelly’s distress when I witness some of what is going on in my Church. But like her, I am too thoroughly formed by Catholicism to be anything else.

After graduating from Notre Dame in 1970, Art McFarland went to the University of Virginia Law School, where he once again was a racial trailblazer, and then served as an Earl Warren Fellow with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in New York, before returning to Charleston. He built a career there as a lawyer and a municipal judge, married and had two children.

He also reconnected with his old parish, Saint Peter’s, which by then had been merged with a formerly white parish, Saint Patrick’s, and was led by a dynamic black priest, Father Egbert Figaro. Among other things, McFarland became a member of the Knights of Peter Claver, a fraternal group for black Catholic men similar to the Knights of Columbus. Ultimately, he became the Supreme Knight and CEO of the Knights of Peter Claver, serving in that capacity from 2000 to 2006. He remains today one of the most prominent and influential black Catholics in the United States.

He feels his conversion back there in sixth grade has proven to have been well worth it.

“Without question,” he says. “There have been all these opportunities to bring about change. Each of us is here with a certain mission. Ours is still not a perfect Church, but it certainly has made a difference in my life. I have no regrets.”

Photo of Arthur McFarland by Milton Morris. All other photos by Matt Cashore.