One dreary day in January, when forecasters predicted that a strong low-pressure system over the western Gulf of Mexico might leave as much as 5 inches of rain in some parts of southeast Louisiana and that strong east winds could push up tides 2 to 3 feet, only eight of the 15 students in André Smith’s fourth-grade class showed up for school.

During a similarly stormy day last fall, Ann Loughery recalls, she had to calm the fears of her kindergartners and first-graders.

“Señiorita Ann, are we going to have a hurricane again?” they asked their new Spanish teacher. “Is another hurricane coming?”

“No,” she told them. “It’s just a hard rain. We’re up on the third floor. The school is going to take care of us.”

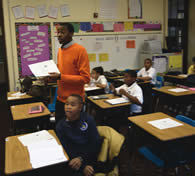

Both 2007 Notre Dame graduates, Smith and Loughery had accepted assignments to work last year at Cathedral Academy, a Catholic grade school housed in a hefty red brick building near the center of the French Quarter. It was the first time Notre Dame’s Alliance for Catholic Education (ACE) program had dispatched teachers to New Orleans.

Before arriving last August, they, like their two ACE housemates who teach at nearby Saint Peter Claver School in Faubourg Tremé, knew New Orleans mostly from its tawdry reputation and the images of poverty, fear and government failure that spread across their TV screens in the early days of their junior year.

Arriving for their two-year teaching commitments felt like stepping into the looping video reel that played for days after Hurricane Katrina. Rachel Pleis, a 2007 graduate of the University of California, San Diego and an ACE teacher, recalls one of her first spins through her new Lower Garden District neighborhood.

“We saw the Wal-Mart that on TV was always being looted,” she says. “Now we’re shopping at it.”

To discover the true nature of New Orleans after the flood, however, these teachers say they have looked beyond place—and into the faces of their students. The evidence revealed itself quickly, they say, as the first semester started with children and their teachers gathered for prayer services making Katrina’s second anniversary.

“The priest asked, ‘How many of you are still living in a trailer?’ Almost half of my kids raised their hands,” Pleis says. “He said, ‘Raise your hand: How many of you lost your home? How many of you lost relatives?’”

These children, the teachers say, possess uncommon maturity and empathy. In their short lives, many have lost all of their possessions. Some swam out of their homes for survival. All began the 2005-06 academic year at a strange school, many in a strange state. Moving back to New Orleans, they have shared cramped FEMA trailers with nine or 10 relatives. They wear donated shoes and color with donated crayons. They save their pennies for the homeless because they know how it feels.

“With everything else these kids have going on in their lives, it’s hard to understand why they want me to teach them fractions,” says Brendan McKiernan, who graduated from Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology before starting the ACE program last year.

But as much as Katrina lingers as the milieu of life in this city, not least of all when dark clouds gather, their students rarely talk directly about the hurricane, the ACE instructors say.

Instead, these children prefer to educate their teachers in the traditions of their hometown, from the flamboyant bead-and-feather costumes of the Mardi Gras Indians who rove the city during Carnival to the delicacy of biting open the wrapper of a spicy, shrink-wrapped pickle at lunch time.

“My kids, they don’t really know that they’re a part of the rebuilding, but they are,” Smith says. “They have that love. They say, ‘This is my home.’”

Michelle Krupa is a reporter at The (New Orleans) Times-Picayune. She can be reached at krup78@hotmail.com.

Photo by Matt Cashore ’94