Growing up, our Mayberryish town was small enough that the teachers at school knew each family. The line of Hunts became a coveted addition to the classroom each fall. It wasn’t because we were particularly brainy or helpful. Truthfully the teachers may not have wanted us at all. They just wanted my mom’s famous soda bread.

The night before St. Patrick’s Day my mother would roll up her sleeves and make a full-size soda bread for each child’s teacher, in addition to one for our home and another one or two for neighbors or family members who had put in a request.

For those who have never made a soda bread, or for those who have used a spoon to make it instead of their bare hands and so have not made a true Irish soda bread, let me explain that making that many soda breads is a labor of love and of extreme upper body strength. The dough is thicker than any other I’ve kneaded or formed, and occasionally your hands get caught in the tangle of buttermilk and flour and sugar and a second person is required to extract them.

In my mother’s case baking soda bread also required extreme patience as we only owned one cast-iron skillet — and the only way to get the bread perfectly brown is in a cast-iron skillet. This skillet is to be used only for soda bread. At our house, failure to obey this rule was once the cause of a marital spat when it was used to cook beef and then, to the well-trained palate, the ensuing batch of soda bread tasted slightly meaty. Sure, you could shape soda bread on a cookie sheet or mold it into scones, but then you’d have sacrificed the integrity of soda bread, so why make it at all? You wouldn’t. So my mother would plop one chunk of dough in the pan, bake for an hour, pop it out to cool and start on the next one. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

The other thing to understand about Irish soda bread is that it is — forgive me, o ancestors — typically disgusting. As you well know, the Irish went through a famine, and I occasionally wonder if, even since prosperity’s return to the island, they’ve continued to mix sawdust in with the dough, because that is truly the closest taste association I can make for many of the soda breads that have touched, and then been spat out from, my lips. It is often so dry and crumbly that it becomes no more than a vehicle for good Irish butter or clotted cream or jam.

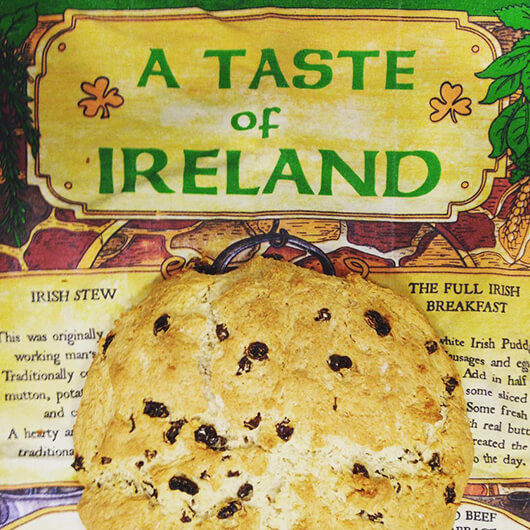

But my mother’s is different. Bias aside, my mom’s is the best. More cake than bread, it’s sweet and moist and has just the right amount of raisins, which is a delicate balance, teetering on the edge between stingy and overkill. Even my grandmother’s is not as good, and I think if persuaded, despite her stubborn Irish nature, she might even admit that. Instead, my mom’s recipe is from a family friend who came over from County Kerry and brought with her a perfect soda bread recipe whose origins and particulars are secret.

And secret the recipe remains. Many of those elementary school teachers asked for the recipe when the Hunts concluded their tenure at the brick school, but it stays guarded. It was also unwritten, stored in my mother’s memory until I begged her to give it to her eldest child. ‘Begged’ may be an exaggeration, but we’re Irish and tall-tale-telling is a genetic inheritance.

Alas, my husband is only a fraction Irish and does not share my affinity for raisin-pocked bread, but the neighbors swarm on St. Paddy’s, knowing a warm bread and full bottle of Jameson awaits.

Now that the yarn has been spun, it’s time to knead my own batch. Then to plop it in my own cast-iron skillet, which was used to cook a steak not two nights ago. Pray for the soul of the man who betrayed my skillet.

Tara Hunt McMullen is a freelance writer and former associate editor of this magazine.